CONFERENCE COVERAGE SERIES

Alzheimer's Association International Conference (AAIC) - 2023

Amsterdam, Netherlands and Online

16 – 20 July 2023

CONFERENCE COVERAGE SERIES

Amsterdam, Netherlands and Online

16 – 20 July 2023

Change was in the air at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, held July 16-20 in Amsterdam. With the first treatment in 20 years having just earned traditional approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, another with accelerated approval, and a third with positive Phase 3 data, Alzheimer’s researchers marked the end of a long drought, and made plans to build on these gains. Some 7,500 people attended in person, and another 3,500 viewed talks online. A third of attendees were under 35, more than 60 percent were women, and almost a fifth were from low- and middle-income countries, noted the association’s Maria Carrillo.

“I’ve never experienced such a positive vibe at AAIC,” said Philip Scheltens, who has been part of this conference for the last 35 years. “We’ve waited so long [to have new treatments], and now we’re there.” Scheltens, newly retired from leading the Alzheimer’s Center at VU University Medical Center in the meeting’s host city, received the Alzheimer’s Association’s Bengt Winblad Lifetime Achievement Award at AAIC. Many subsequent sessions were introduced by his successor, Wiesje van der Flier, who shares directorship of the Alzheimer’s Center with Yolande Pijnenburg.

In a further sign of how drug approvals are changing the field, the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced its plan to end restrictions on covering amyloid PET scans July 18 during AAIC. In effect since 2013, the previous policy had limited beneficiaries to a single scan per lifetime, and only for those participating in a clinical trial (Jan 2013 news; Oct 2013 news). In its proposed decision memo, the agency noted that this once-per-lifetime restriction was no longer appropriate, given the development of anti-amyloid treatments.

Against this backdrop, sessions in Amsterdam featured numerous talks on amyloid immunotherapy. Other notable topics included Down’s syndrome—a genetic form of Alzheimer's that could potentially be treated with such antibodies but has not been studied for that purpose—and anti-tau antibodies and their potential for concurrent trials. A symposium on proposed revisions to the NIA-AA criteria for diagnosing AD drew keen interest. So did sessions on reviving BACE inhibitors, inflammation and vascular contributions to dementia, ADRD biomarkers beyond Aβ and p-tau, the LEAD cohort of early onset AD, APOE research, and many other topics (see upcoming conference stories).

This story summarizes the first in-depth look at Phase 3 data from donanemab, which were discussed July 17 in Amsterdam, and published in JAMA the same day. In Amsterdam, Eli Lilly’s Mark Mintun said the company has applied for traditional approval from the FDA, and will file in other countries this year. Lilly has begun a new safety and efficacy trial, Trailblazer-Alz5, focused on countries outside the U.S.

Diverging Curves? In the primary analysis population, donanemab (green) slowed cognitive decline compared to the placebo group (gray) on the iADRS (left) and CDR-SB (right), with curves continuing to diverge over 18 months. [Courtesy of Eli Lilly.]

Donanemab Benefit Robust, Grows Over Time

Lilly had released Phase 3 top-line results from Trailblazer-Alz2 two months ago, reporting that donanemab slowed decline on the primary and all secondary clinical endpoints by about a third in the primary analysis population, who had low-to-intermediate tau tangle loads (May 2023 news). In Amsterdam, Lilly’s John Sims filled in details. At 18 months, the absolute difference between treatment and control groups was 3.25 points on the iADRS, and 0.67 on the CDR-SB. The latter was slightly larger than the 0.45 points seen with lecanemab, and the 0.53 points notched in the one positive aducanumab trial. Those trials did not use the iADRS.

The Trailblazer-Alz2 cohort was slightly further along in the disease compared to those in other trials, Mintun noted. Participants were about two years older, at an average age of 74. Their baseline MMSE was 23, their plaque load 102 centiloids. These numbers were similar to participants in the negative gantenerumab Phase 3 trials, but more advanced than the population in the positive lecanemab Phase 3 trial, which had an average MMSE of 26 and amyloid load of 76 centiloids (Dec 2022 conference news).

The difference between the donanemab and control groups became statistically significant as early as three months for the iADRS, and at six months for the CDR-SB. The curves continued to separate over 18 months, as expected for a disease-modifying therapy, Mintun said. At 12 months, the numerical difference between treatment and placebo groups was 2.62 for the iADRS and 0.59 for the CDR-SB, both less than the difference at 18 months. The researchers are continuing to follow participants in a further 18-month open-label extension, which is still blinded to the original treatment groups. This will generate data on how the treatment effect evolves over three years.

In Amsterdam, several scientists continued their argument for measuring delay in progression in units of time, rather than numerical differences or percent slowing of decline (Apr 2023 conference news). On this “time saved” scale, donanemab delayed progression on the iADRS by 4.5 months, and on the CDR-SB by 7.5 months, Liana Apostolova of Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis reported in Amsterdam.

The findings were reported to be robust to sensitivity analyses. Efficacy results did not much change when the analyses were adjusted to account for dropouts, when excluding participants who had ARIA, or when using different statistical methods. In all scenarios, donanemab slowed progression between 33 to 40 percent, Sims said.

Slice and Dice by Tau. The Trailblazer-Alz2 trial focused on people with low to intermediate tangle load (middle), the only statistically powered group. Gains were smaller in a high-tau group (right). People with very little tau PET signal (left) were not enrolled, nor followed observationally. [Courtesy of Eli Lilly.]

Treatment Effect Apparent in Early Disease, at Intermediate Tau Loads

In prespecified analyses of the primary outcome data, donanemab appeared to work best at a narrowly defined disease stage. The clinical benefit was largest in the subgroup with mild cognitive impairment. Their decline slowed by 60 percent on the iADRS and 46 percent on the CDR-SB. Grouping participants by age revealed slightly more benefit in those under 75, with decline slowed by 48 percent on the iADRS and 45 percent on the CDR-SB.

Other factors did not seem to matter. The researchers found no difference between men and woman, unlike in the Phase 3 gantenerumab trials, which had a greater effect in men (Apr 2023 conference news). In those trials, women at baseline had worse tau tangles than men, whereas Trailblazer-Alz2 selected participants based on tangle load, resulting in more uniformity on this measure.

Racial and ethnic subgroups were too small to draw conclusions. Lilly has added an ongoing safety addendum to the trial and is using this to try to boost diversity, Mintun noted. There was no difference between APOE4 heterozygotes and noncarriers. The treatment benefit appeared to be slightly less in APOE4 homozygotes, but this subgroup was small and underpowered.

Tangle load did matter, however. The RCT trial population, comprising 1,182 people and used for all the above analyses, had baseline tau PET scans between 1.10 and 1.46 SUVr. Trailblazer-Alz2 enrolled an additional 554 people with scans above 1.46. This high-tau subgroup notched barely 20 percent slowing of decline on the CDR-SB, and below 10 percent on the iADRS. The former was statistically significant, the latter not, though Sims noted that this subgroup was not powered to show significance. Baseline amyloid loads were the same regardless of tangle burden.

This curation of a treatment group by tau PET drew both praise and questions. Christopher van Dyck of Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, called these staging data valuable but noted that as many as a quarter of people with early AD have tau PET loads below 1.10 SUVr. Should this group be treated with donanemab? This registration trial gives no data on this question, as it excluded them.

Sims noted that this population, which Lilly considers to be basically “no tau,” is being evaluated in Trailblazer-Alz3, which enrolls people at the preclinical stage of disease. That trial is not expected to read out until the end of 2027 (Jul 2021 news). This answer did not fully satisfy everyone. In hallway talk at AAIC, several clinician-researchers said they'd prefer to also have data on how donanemab performs in people with mild symptoms and very low tau, many of whom will seek treatment at memory clinics.

Others asked whether tau PET scans will be necessary before treatment with donanemab, so that treating physicians can target the same population as those who benefitted in the trial. Sims argued that this is not needed, given that the combined intermediate- and high-tau groups still showed a statistically significant treatment benefit. Oskar Hansson of Lund University, Sweden, who analyzed biomarker data for Lilly, noted that because people with high tangle loads have a different risk-benefit ratio for treatment, it would be helpful to test for tau burden before prescribing anti-amyloid antibodies. Ideally, this would be done with a blood test rather than tau PET, due to the high cost and limited availability of the latter. Such plasma tests are in development, but not yet broadly available.

Most Biomarkers Moved Toward Normal, But Tangles Stayed Put

The biomarker data from this trial shown at AAIC largely tracked with the clinical findings. Results were similar in the low-to-intermediate tau group, and in the combined analysis with the high-tau group included. As expected, donanemab rapidly removed an average of 88 centiloids of plaque over 18 months. The drop was fastest in the first six months, with a third of participants becoming amyloid-negative then. By the end of the trial, 80 percent had crossed this threshold.

This is faster than with aducanumab. In Amsterdam, Lilly’s Andrew Pain reported 12-month data from the head-to-head comparison of these two drugs in the open-label Trailblazer-Alz4 trial. Six-month data had shown faster clearance with donanemab, in part due to its quicker titration to the effective dose (Dec 2022 conference news). That pattern continued, with donanemab removing 80 centiloids compared to aducanumab's 56, by one year. In this study, 70 percent of people taking donanemab were amyloid-negative by one year, compared with 22 percent on aducanumab.

In the Phase 3 study, plasma tau biomarkers followed plaque. Plasma p-tau181 dropped almost 20 percent on drug, p-tau217, 40 percent. In keeping with the subgroup analyses showing more clinical benefit at earlier stages, people who were in the lowest p-tau217 tertile at baseline did best, declining on the CDR-SB by 46 percent less than placebo, compared with 27 percent less for those with higher baseline p-tau217. This post hoc analysis used the combined tau groups.

Plasma GFAP, a marker of inflammation, fell 21 percent on drug. Plasma NfL, thought to denote neurodegeneration, was mystifying. It initially rose in the donanemab group, before dropping back to slightly below baseline levels by 18 months. Sims noted that this marker varies greatly from one person to another, but did not show spaghetti plots.

As in other amyloid immunotherapy trials, brain volume decreased on donanemab, though hippocampal volume loss resembled that on placebo. The field is grappling with what this accelerated shrinkage means (Apr 2023 news). At AAIC, too, the discussion reprised current arguments that global volume loss perhaps reflects cortical “pseudo-atrophy” as amyloid and attendant inflammation decrease, whereas the hippocampus has little amyloid to begin with.

The most surprising and, to some, concerning finding was that donanemab did not affect tangle growth as measured by tau PET. In Phase 2, the antibody had appeared to slow, though not stop, tangle accumulation in the frontal cortex, with a trend toward slowing in the parietal and temporal lobes (Mar 2021 conference news). In the Phase 3 trial, the tau PET curves of placebo and treatment groups were superimposed.

Hansson noted that ongoing regional analyses may yet surface subtle effects. A post hoc analysis of these Phase 3 data suggested that participants who became amyloid-negative during the trial had less tangle accumulation than those who remained amyloid-positive, Hansson added. Here, too, 18 months of additional study may be instructive.

Staying Power. In participants who stopped donanemab after having dipped below the amyloid threshold by one year, trial outcomes continued to diverge from those who had always been on placebo (arrows). [Courtesy of Eli Lilly.]

What Happens When Treatment Stops?

A unique aspect of donanemab is that treatment stops once plaque load drops below the positivity threshold. In Trailblazer-Alz2, this happened in two-thirds of participants across both tau groups. What did this do to their subsequent clinical progression?

To answer this, Lilly researchers analyzed nearly 300 people who became amyloid-negative at an average of 47 weeks. Their clinical progression continued to diverge from the placebo group, reaching a difference of 3.52 points on the iADRS and 0.75 on the CDR-SB by 18 months, slightly larger than the overall trial benefit.

In Amsterdam, Lilly’s Sergey Shcherbinin presented data on plaque re-accumulation in participants of the earlier Phase 2 study. Analyzing 47 people who became amyloid-negative, with an average final plaque load of 4.7 centiloids, Shcherbinin found that they added about 2 centiloids over the following year. This is similar to the rate of plaque accumulation in the ADNI observational study, even though this trial population has higher tangle loads on average than the ADNI cohort, Shcherbinin noted. This rate was the same regardless of how much amyloid people had cleared, or how low on the centiloid scale they got after a course of donanemab.

Adding data from the Phase 3 trial upped the re-accumulation estimate to 2.8 centiloids per year. At this clip, it would take about five years for a person to become amyloid-positive again after clearance, Shcherbinin said.

ARIA: Still a Fly in the Ointment

The risk of ARIA remains a big concern. In its trials thus far, donanemab had ARIA rates in between the 12 percent on lecanemab and 33 percent on aducanumab, with about one-quarter of people on drug developing it. Six percent of people in Trailblazer-Alz2 developed symptoms from ARIA. In almost 2 percent of participants, nearly all of them APOE4 carriers, these symptoms were considered serious, noted Stephen Salloway of Butler Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island. The risk of ARIA was the same in people taking anticoagulant or anti-platelet medication as in the cohort overall.

As with lecanemab, the risk of macrohemorrhage was higher on drug, doubling from 0.2 to 0.4 percent. Three people on donanemab died from brain bleeds during the trial. Two of them were heterozygous APOE4 carriers and developed severe ARIA-E, Salloway said. The third was not a carrier, but had superficial siderosis at baseline, a sign of previous brain hemorrhages. None were on anticoagulants.

Numerous talks in Amsterdam grappled with how to predict the occurrence of ARIA, with a growing number of scientists tying it to cerebral amyloid angiopathy and its attendant inflammation (see upcoming AAIC story).—Madolyn Bowman Rogers

Scientists once hoped that blocking β-secretase would slow or prevent Alzheimer’s disease. Then came the rude awakening. The inhibitors caused the very thing they were supposed to prevent—cognitive decline. Enthusiasm tanked. Pharmaceutical companies canned their BACE inhibitor programs. But a few lone voices kept calling for another try, and by AAIC 2023, held July 16-20 in Amsterdam, the vibe had shifted. A small but vocal group of basic scientists had always maintained that the field gave up too quickly on these compounds, and now some clinicians have come around.

“BACE inhibition in primary prevention holds great potential,” said Paul Aisen, University of Southern California, San Diego, during a scientific session on the future of BACE inhibition. Even Reisa Sperling, a self-professed skeptic of BACE inhibition, said she could envision a small trial. Sperling, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, co-chaired the session with Robert Vassar from Chicago's Northwestern University, who, with Martin Citron, had cloned BACE 24 years ago (Vassar et al., 1999).

What’s changed? For BACE inhibition itself, not much. Secretase experts had always advised low doses to avoid adverse events. That is because BACE not only catalyzes the first step in Aβ production—the cleavage of amyloid precursor protein—but also snips dozens of other substrates. Many are found in neurons; some support axon guidance and synaptogenesis.

What has changed is that scientists now have a way to identify and monitor at least some of those cleavages. In Amsterdam, Stefan Lichtenthaler, Technical University of Munich, reported analysis of cerebrospinal fluid samples taken at baseline and after treatment with three different BACE inhibitors, Merck’s verubecestat, Novartis’s umibecestat, and Shionogi’s atabecestat. The Merck samples came from a Phase 3 trial, while the others came from Phase 2s.

Stephan Muller and Pieter Giesbertz in Lichtenthaler’s lab ran mass-spectrometry-based proteomic analyses of the samples, looking for peptides snipped from cell-surface BACE substrates. “All three BACE inhibitors produced qualitatively and quantitatively similar proteome changes,” said Lichtenthaler. The three inhibitors lowered CSF concentrations of peptides cleaved from the same dozen or so substrates, including Sez6, IL6ST, CACHD1, CHL1, Sez6L, and L1CAM.

BACE Proteomes. These volcano plots show down- (blue) and upregulated (red) protein fragments in the CSF of people who had been treated in BACE inhibitor trials. The profiles for umibecestat (left) and verubecestat (right) were very similar. [Courtesy of Stefan Lichtenthaler, Technical University of Munich.]

These reductions were dose-dependent, and, in the case of the learning and memory-linked protein Sez6, the soluble fragments were almost fully suppressed at the highest inhibitor doses given in those trials. Indeed, reduction of soluble Sez6 directly correlated with reduction of Aβ40 in the CSF.

For some other substrates, however, BACE inhibition, even at the highest doses, only partially reduced their soluble fragments, suggesting other proteases help process them. This was the case for the neural cell adhesion molecules L1CAM and CHL1, for example. Whether that absolves these substrates from any part in the cognitive decline caused by BACE inhibition in the trials remains to be seen.

Nobody knows for certain which of the BACE substrates are needed for cognition. Jochen Herms, Ludwig-Maximilians University, Munich, believes Sez6 is important. At AAIC, he reported that in Sez6 knockout mice, spine density is a bit below that of control mice, but that verubecestat and other BACE inhibitors did not reduce it further. The data suggest that spines supported by this neuronal signaling molecule are vulnerable to BACE inhibition.

Importantly, Lichtenthaler noted that reductions of all these soluble fragments in the CSF reached a maximum at even the lowest doses of umibecestat and verubecestat used in the clinical trials—15mg and 12mg, respectively. Partial suppression occurred in the case of 5 mg atabecestat, which, incidentally, caused no significant cognitive decline. “Cognitive worsening only occurs at drug doses where BACE1 substrate cleavage is nearly maximally inhibited,” Lichtenthaler concluded.

He believes that low doses of BACE inhibitors would allow sufficient substrate cleavage to still occur such that cognitive decline would be avoided, while also sufficiently slowing amyloid accumulation. He said trials to test this hypothesis should collect enough CSF to correlate cleavage of these BACE substrates with any cognitive changes.

What could such a trial look like? Julie Stone, a pharmacokineticist at Merck, has been crunching the numbers on such questions for years (e.g., May 2015 webinar). Stone modelled two scenarios discussed in Amsterdam—primary prevention among people who have tested positive for low levels of amyloid, and a post-immunotherapy “maintenance dose” to keep plaques from regrowing once they had been cleared. In both cases, Stone estimated how BACE inhibition would affect plaque load.

Regarding prevention, Stone concluded that a high dose of verubecestat, or around 27 mg daily, would be needed to halt amyloid growth at a stage where baseline levels are around 10 centiloids. Such a high dose would be needed because, in kinetic terms, plaque growth is a zero-order process, proceeding fastest early in pathogenesis. Alas, that 27 mg dose would suppress Aβ production by 80 percent, a level associated with cognitive side effects in prior trials.

What about when baseline amyloid levels are higher? Perhaps counterintuitively, Stone's model predicted that lower doses of inhibitor would suffice in that case. At a baseline of 50 or 60 centiloids, daily doses of 2.9 mg or 1.7 mg verubecestat, respectively, would prevent further plaque growth. Whether this would slow progression of the disease, including tau pathology and cognitive decline, is unknown, Stone said. The 1.7 mg dose would inhibit BACE by a third, likely low enough to avoid cognitive side effects.

Rather than stopping plaque growth, what about slowing it down? Stone modeled what 35 percent BACE inhibition at various baseline amyloid loads would achieve. At 10, 25, or even 50 centiloids, this would limit plaque growth to reach 50 to 60 centiloids after 20 years, instead of the 80 to 90 centiloids that would be reached in untreated controls.

“The big open question is, is that clinically meaningful?” Stone asked at AAIC. Many AD-related pathologies and symptoms don’t show up until plaque loads surpass 50 centiloids, suggesting this slowing could be beneficial. “Instinctively, we expect that slowing of amyloid would slow progression of the disease,” she said.

Slow Those Plaques Down. Kinetic modeling suggests that 1.7 mg verubecestat, given when amyloid burden had reached 10 (blue line), 25 (red line), or 50 centiloids (yellow line), would slow plaque growth relative to untreated controls (dashed lines). [Courtesy of Julie Stone, Merck.]

Stone predicted a similar scenario if BACE inhibitors come in after immunotherapy has removed plaques. Around 12 mg verubecestat would be able to maintain a 20 centiloid plaque load. That is in the range known to cause cognitive deficits. A dose of 1.7 mg would slow regrowth, again plateauing at about 50-60 centiloids after 20 years.

What about real-life experiments? Preclinical work makes low-dose inhibition look attractive. Elyse Watkins, a postdoc in Vassar’s lab, treated 8-month-old PDAPP mice with 109, 33, or 11 mg/Kg of MBi-10, a BACE inhibitor from Merck. Six months later, mice on the lowest dose had 40 percent less amyloid than untreated controls. The human equivalent dose would be around 0.9 mg/Kg, likely sparing cognition.

Watkins’ data suggests that this dose might even help clear plaques. She had injected the 8-month-old animals with Methoxy O4 to label existing plaques. At 14 months, she measured less of the label in treated mice than in controls, suggesting that some of the plaque present at baseline had cleared.

Going Low. At a low dose of 11 mg/Kg, the BACE inhibitor MBi-10 reduced soluble Aβ42 and plaque load in the cortices and hippocampi of PADPP mice. It even cleared some of the Methoxy O4 injected into the brain six months prior, hinting that it may help clear existing plaques. [Courtesy of Elyse Watkins, Northwestern University.]

Are trialists ready to try? “We have to be very careful,” Sperling told Alzforum. She is concerned about suppressing soluble Aβ. Like BACE inhibitors, solanezumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds monomeric Aβ, also tended to cause cognitive decline in the A4 secondary prevention trial, though without affecting BACE substrates (Mar 2023 news). Dave Morgan, Michigan State University, Grand Rapids, echoed that sentiment. Like others in the field, he thinks Aβ has some important, still-unknown function at synapses.

Even so, Sperling has warmed to the idea of testing these inhibitors once more. “I would be open to a small trial where we test for cognitive changes over a very short time, even as little as a few weeks,” she said.

Aisen is more optimistic. He pointed out that solanezumab did have a small cognitive/clinical benefit in the pooled analyses of two Phase 3 trials in LOAD, and that the solanezumab dose was subsequently increased in A4 (Oct 2012 news; Jun 2017 news). Aisen suspects A4 may have simply lowered soluble Aβ too much for synapses to function properly.

“I think if we embed sufficient cognitive monitoring, we would be comfortable in planning a significant [BACE inhibitor] trial,” he told Alzforum. “Clearly there are cognitive effects, but these are dose-related, reversible, and we can monitor them,” he said.

Aisen believes that in preclinical AD, the A4 trial validated the PACC and RBANS as being sensitive enough to quantify cognitive decline, and would pick up decline caused by BACE inhibition, as well (Mar 2023 news). “I believe we can develop BACE inhibitor trials at lower than 50 percent inhibition, and do it now,” he claimed.

Others welcomed the idea. Ralph Nixon, New York University, noted that BACE inhibition would not only reduce Aβ, but also APP's β-C-terminal fragments. Nixon and others have reported that β-CTFs scupper the endolysosomal system, disrupting proteostasis and exacerbating amyloid pathology (Jun 2010 news; Jun 2022 news; Jul 2023 news).

Lichtenthaler agreed that tempering β-CTF could be an important benefit—as could an increase in sAPPα, a fragment generated by α-secretase, which completes with BACE to cleave APP (Jan 2019 news). “We could have a triple-positive effect of BACE inhibition,” he suggested. Low-dose BACE inhibition might even correct lysosomal dysfunction in AD, he predicted (see Lichtenthaler’s recent comment).

Injecting a cautionary note, Bart De Strooper, University College, London, said that in addition to suppressing cleavage of BACE's other substrates, inhibitors would also lead to more of the shorter, more hydrophobic Aβ peptides generated by α-cleavage of APP between amino acids 16 and 17 of the Aβ peptide sequence. Also called p3 fragments, these Aβ17-x peptides tend to be neglected, but can insinuate themselves into plaques (Iwatsubo et al., 1996). “These are difficult to detect, but I would not overlook them,” said De Strooper.

De Strooper wants to see γ-secretase modulators (GSMs) reconsidered. “Mechanism-based side effects that are difficult to circumvent are always a struggle with BACE inhibitors,” he said. “With GSMs, you aim to lower the toxic Aβ fragments instead of lowering total Aβ. This is a better rationale, because you keep all other biology intact.”

Lichtenthaler countered that the protective Icelandic A673T mutation in APP, which slows its cleavage by BACE and reduces Aβ production by a third, supports the rationale for BACE inhibition, as do mice having only one copy of the BACE1 gene (Maloney et al., 2014). The latter lack the neurological dysfunction of the full knockouts.

BACE inhibitors have been tested up to Phase 3 and could be retested without delay. “I’m pretty convinced low-dose BACE inhibition will work,” said Lichtenthaler.

What would such a trial look like? Aisen is enthusiastic about both types of trial Stone modeled, one for primary prevention and one to augment immunotherapy. Whether pharmaceutical companies would be willing to restart their BACE programs remains to be seen.

“I’m not confident we’ll get that kind of support, but am optimistic that pharma will be willing to supply the drugs,” Aisen said. One pharma scientist told Alzforum her company would likely sell its BACE inhibitor for $1 to a group able to fund and run new trials.

One possibility is an A2 trial akin to the A3 and A45 trials of lecanemab targeting people with amyloid levels between 20 and 40 centiloids, and above 40 centiloids, respectively. Aisen and Sperling are investigators on both. Indeed, the A3 trial was initially slated to test a BACE inhibitor until the cognitive side effects put the kibosh on that. “It seemed plausible then, and it seems plausible now, that BACE inhibition will have a clinically meaningful effect,” said Aisen.

As for A2, Aisen said the goal was always to go lower, to 20 or 10 centiloids. He believes it may be possible to treat people before they test positive for amyloid, using plasma tests for various p-taus or Aβ42/40 as indicators of imminent amyloid deposition. “We are discussing A2,” noted Aisen. “Our intention is to continue to move earlier, toward primary prevention, but we are not ready to pin down a trial design,” he told Alzforum.

“Our goal is to devise a path forward for new clinical trials to test low-level BACE inhibition,” said Vassar, “because we are going to need an oral disease-modifying therapy for Alzheimer’s disease.” De Strooper agreed. "It is extremely important to emphasize that anti-amyloid antibodies cannot be the primary prevention we are all looking for.” —Tom Fagan

More than a decade before memory loss, fragments of phospho-tau start to rise in biofluids. These biomarkers, particularly p-tau217, have proven to be exquisite detectors of amyloid, but they plateau once symptoms surface and don’t track tightly with tau tangles. Here’s where MTBR-tau-243 comes in. According to a paper published July 13 in Nature Medicine, this particular fragment from tau’s microtubule-binding domain rises in step with tau-PET, and continues to climb even in the symptomatic stages of AD. Led by Randall Bateman of Washington University in St. Louis and Oskar Hansson of Lund University in Sweden, the study found that, more than any other tau biomarker tested so far, MTBR-tau-243 also correlates with cognitive decline, offering clinicians an important tool for both diagnosis and prognosis. What’s more, the putative tangle detector comes at a time when it’s sorely needed for tracking treatment responses in trials aimed at tau.

Case in point, at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, held July 16-20 in Amsterdam, first data from early phase trials of Eisai’s E2814—an antibody that binds tau’s midsection—indicate that the drug safely engaged its target in people with familial AD. Importantly, it also cut CSF MTBR-tau-243 in half. Together, these findings hint at the possibility that finally, a tau antibody may be putting a dent tau tangles. Of course, the field still needs to find out if this target engagement stems cognitive decline.

In the AD brain, tau tangles comprise fibrils with a C-shaped protofilament core, which itself includes the third and fourth microtubule binding domains near the C-terminus of the protein (Jul 2017 news). Yet it is N-terminal fragments of phosphorylated tau, including p-tau181 and p-tau217, that are secreted by neurons in response to amyloid accumulation, making them sensitive fluid biomarkers for amyloid, not tau tangles (Mar 2018 news).

In search of chunks of tau in fluids that would signal the presence of tangles without the need for costly tau-PET scans, the WashU team previously identified MTBR-tau-243. Among a small number of participants in the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network (DIAN), the researchers found that the mid-section fragment tracks with tau-PET and disease progression (Dec 2020 news).

The new study tests MTBR-tau-243 in two sporadic AD cohorts: Swedish BioFINDER-2, and the Knight AD Research Center. First author Kanta Horie, an Eisai-sponsored professor at WashU, and colleagues used mass spectrometry to measure MTBR-tau-243, as well as several phospho-tau markers, in the CSF of 448 BioFINDER-2 and 219 Knight ADRC participants. Both cohorts included people across the spectrum of AD, but BioFINDER-2 has a higher proportion of cognitively impaired people. Horie et al. asked which CSF markers tracked most closely with amyloid- and tau-PET. All phospho-tau markers were measured as a ratio of phosphorylated to unphosphorylated tau. When it came to tracking with amyloid-PET, p-tau217 emerged as the clear winner. For tau-PET, MTBR-tau-243 did the best. More than any of the p-tau species, MTBR-tau-243 tracked with tau-PET signal across all Braak regions.

Viewed from a different angle, the researchers found that amyloid-PET explained most of the variation in CSF p-tau217, while tau-PET best explained variability in MTBR-tau-243. In contrast, p-tau205 variability was equally accounted for by amyloid- and tau-PET.

Pin the Tail on the Tangle. Percentage of variation in each CSF biomarker explained by amyloid-PET (blue) versus tau-PET (green). Most of the variation in p-tau231, 181, 217 was explained by amyloid; p-tau205 was equally explained by both. Tau-PET accounted for most of the variance in MTBR-tau-243 (right). [Courtesy of Horie et al., Nature Medicine, 2023.]

How would MTBR-tau-243 change as AD progressed? Among 220 participants in BioFINDER-2 who had serial CSF measurements, the scientists found that p-tau217, p-tau181, and p-tau231 increased dramatically when people became amyloid-positive, then plateaued when they became tau-positive. In contrast, MTBR-tau-243 hardly changed in response to amyloid positivity, but shot up once tau tangles had inundated the brain. The finding suggests that once a person becomes tau-PET positive, MTBR-tau-243 is the marker that best reflects their further disease progression. In line with this, MTBR-tau-243 tracked more closely than any other CSF biomarker with sinking scores on the mini-mental state exam (MMSE).

Finally, the researchers used an algorithm to pick out which combinations of fluid biomarkers best predicted amyloid accumulation, tau tangles, and cognitive decline. For amyloid, p-tau217 was the best single predictor; a combination of p-tau217, p-tau205, and Aβ42/40 did even better. For both tau-PET and MMSE, MTBR-tau-243 was the best single predictor. However, combining it with p-tau205 improved predictions for both measures. In fact, a combination of p-tau205 and MTBR-tau-243 rivaled tau-PET in predicting cognitive decline.

Hansson thinks the marker has both diagnostic and prognostic potential, particularly when used as part of a panel of fluid biomarkers for Aβ and tau. Because biomarkers such as p-tau217 rise many years before cognitive symptoms surface, and then plateau, a positive result leaves open the possibility that a person’s current cognitive impairment is caused by something other than AD, Hansson said. If MTBR-tau-243 was also elevated, this would give clinicians more confidence in calling AD the culprit. The marker will be most useful if detected in plasma, Hansson said, and researchers are working on that now.

Bateman agreed about the biomarker’s potential in the clinic. He also thinks it could help clinicians predict how well a given patient might respond to a therapy such as lecanemab, which worked better among people with low tau accumulation, as measured by PET, than among those with a high tau-PET signal. The same was true for donanemab, as reported at AAIC (see Part 1 of this series)

Gil Rabinovici of the University of California, San Francisco, noted that while convincing at the group level, the correlations between CSF MTBR-243 and tau PET are dogged by significant variability among individuals. “I think the utility of this biomarker for disease staging at the individual patient level is still to be determined,” he commented, adding that the impact of the new biomarker will depend on whether it can be detected in plasma. “With these caveats, MTBR-tau243 seems to be an interesting new biomarker, and it is especially exciting to see it utilized to measure target engagement in early phase clinical trials of MTBR-targeting tau antibodies,” Rabinovici wrote (comment below).

CSF MTBR-tau243 made its trial debut at AAIC, when Jin Zhou of Eisai presented findings from early-phase studies of E2814, a monoclonal IgG1 antibody that binds to the second and fourth microtubule-binding domains of tau. The researchers propose that the antibody intercepts seeding-competent, MTBR-containing fragments of tau released from cells, thwarting propagation of tau pathology.

Zhou showed findings from a multiple-ascending-dose study in 40 healthy participants, as well as results from a separate study conducted in people with dominantly inherited AD (DIAD). The latter included seven participants with mild to moderate dementia, who were slated to receive monthly infusions of E2814 over 18 months. Over that time, doses increased from 750 mg to 4,500 mg. The DIAD study is ongoing, and the remaining participants have reached the highest dose.

At AAIC, Zhou reported that the drug was safe and well-tolerated at all doses tested, in both healthy volunteers and those with AD. One person had two serious adverse events not attributed to treatment. Three of the seven participants in the DIAD trial dropped out due to cognitive deterioration, an expected problem in studies that include people with moderate dementia, Zhou told Alzforum. Among those with AD, target engagement appeared robust in the CSF, as the researchers detected dose-dependent binding of the antibody to both epitopes within tau’s MTBR.

Among the five participants with AD in which MTBR-tau-243 was measured, its concentration in the CSF plummeted in response to E2814 treatment. For four participants, it dropped between 40 to 70 percent within the first three months, in response to the lowest dose used. For one participant, the biomarker did not drop until dosing was doubled to 1,500mg; then it declined more slowly over the following months (see below).

Taking Down Tangles? CSF-MTBR-tau243 dropped in response to treatment with E2814 in people with dominantly inherited AD. [Courtesy of Jin Zhou, Eisai.]

The biomarker findings suggest that E2814 lowered MTBR-tau-243, but did it knock down tangles? Only post-treatment tau-PET scans will tell. Zhou expects that scan data from the remaining participants within the next few months. “We are anxious and excited about that data,” she said.

Einar Sigurdsson of New York University believes the therapeutic potential of E2184 is well supported by its reduction of MTBR-tau-243. However, he noted that the majority of the antibody’s target is inside of neurons. “With this in mind, it would be interesting if the company examined whether the antibody is taken up into neurons, which would then greatly increase the pool of targetable tau,” he wrote. “If it is not, then it may be efficacious at a lower dose if its neuronal uptake could be enhanced, for example by altering its charge (Congdon et al., 2019).

Tiny single-domain antibodies are also being developed to target intracellular tau (May 2023 conference news). Sigurdsson added that an antibody’s ability to prevent tau seeding versus toxicity may not always go hand in hand. “It will be important to determine if this antibody and related ones against the MTBR region can reduce tau neurotoxicity in vivo, and reduce functional impairments,” he wrote.

E2814 is currently being evaluated in the DIAN-TU Tau NexGen trial, concurrently with lecanemab. The trial is running at 39 locations around the world, and expected to finish in 2027. Zhou said the new tangle-tracking biomarker comes at a perfect time, and the researchers are planning to integrate this measure into the ongoing DIAN trials. “There will be a cross-validation, for both the biomarker and the drug,” Zhou said.

Bateman said he expects the marker to be deployed broadly in clinical studies targeting both Aβ and tau. “If we start using it more across the trials, it will give us more information on this part of the pathology, so we can make better decisions based on what the drugs are doing.” For example, it could be possible that amyloid-targeted therapies that lower p-tau217 but not MTBR-tau-243 are less effective at slowing cognitive decline than drugs that lower both.

E2814 forms part of a field of MTBR-targeted therapies wending their way through preclinical and early clinical development. At AAIC, scientists from Prothena presented findings from the first in-human dosing of PRX-005. This human monoclonal antibody recognizes three epitopes within the first, second, and third microtubule-binding domains of tau. The single-ascending-dose study included 25 healthy participants, who received one of three doses of the antibody, or placebo. The drug appeared safe at all doses tested, and reached a sufficient concentration in CSF, suggesting it successfully crossed the blood-brain barrier. Currently, a multiple-ascending-dose study is ongoing in people with AD.

Prothena also reported preclinical findings on PRX-123, a dual peptide vaccine against Aβ and tau. The vaccine comprises the N-terminus of Aβ and the MTBR region of tau, complexed to an adjuvant that riles T-helper and B cells. At AAIC, Prothena reported that APP/PS1 mice immunized with PRX-123 produced a robust antibody response, and that antibodies in the mice's sera bound to both Aβ plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles in brain sections from people with AD. The immunization also substantially lowered plaque burden in mice. —Jessica Shugart

No Available Further Reading

When people think of early onset Alzheimer’s disease (EOAD), autosomal-dominant mutations in the APP or presenilin genes come to mind. But these account for fewer than 15 percent of EOAD cases. For the remainder, the Longitudinal Early-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease Study (LEADS), a collaboration led by Liana Apostolova at Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Brad Dickerson of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Gil Rabinovici at the University of California, San Francisco, and Maria Carrillo of the Alzheimer’s Association aims to characterize their disease and decipher its root cause. At AAIC, held July 16-20, scientists shared baseline and longitudinal data on genetics, imaging, and fluid biomarkers.

“Our ultimate goal is to launch clinical trials," Apostolova wrote to Alzforum. "We consider EOAD to be the ideal Phase 2 cohort, because these young patients have a ‘pure’ form of AD and few medical comorbidities, yet advance rapidly” (full comment below).

What is Early Onset AD?

Sporadic EOAD strikes before age 65. Because of their young age, people with EOAD have largely been excluded from research. They might make for a suitable clinical trial population, because they have few co-pathologies and their disease progresses rapidly. What causes EOAD is unknown, but scientists believe the answers may lie in undiscovered genetic risk variants.

While most adults with EOAD primarily have memory problems, a greater proportion than is the case in LOAD are diagnosed with rare, non-amnestic subtypes, including primary progressive aphasia (PPA) or posterior cortical atrophy (PCA; Jul 2012 conference news). At AAIC, Angelina Polsinelli of Indiana U described two such cases from LEADS.

A 55-year-old man developed progressive memory and language problems over 18 months, which cost him his job because he mispronounced words, asked people to repeat themselves, and could no longer follow directions. His Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) score was 17 out of 30, working memory and language being weakest. He scored 29 out of 60 on the Boston Naming Test, on which controls his age score in the 50s. MRI showed an abnormally small left lateral-temporal lobe, an area that is key to speech and language and is often atrophied in PPA. Since his cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42/40 ratio was low, CSF total tau and phospho-tau181 high, and amyloid and tau PET scans positive, his diagnosis was PPA due to AD.

A 56-year-old woman struggled with depth perception and finding her way. She'd swerve out of her lane while driving and got lost going to the grocery store or doctor’s appointments. Her memory began declining two years later. Her MMSE was 22, with visuospatial perception faring worst. When copying an image, her version appeared “exploded,” a quintessential sign of PCA (McMonagle and Kertesz, 2006). Indeed, MRI showed shrunken temporal, parietal, and occipital cortices. Her low CSF Aβ42/40 ratio, high CSF t-tau and ptau-181, and positive amyloid and tau PET scans prompted a diagnosis of PCA due to AD.

Looks Like PCA. A woman with EOAD rendered a typically disjointed copy of a drawing and was diagnosed with PCA. [Courtesy of Angelina Polsinelli, Indiana University.]

The LEADS Cohort

Most EOAD cases are not so easily defined. PPA and PCA each account for 6 percent of the LEADS cohort, which was created to characterize EOAD cases that lack a clear clinical diagnosis. Designed after the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), LEADS will enroll 400 and 100 cognitively normal adults, ages 40 to 64, at 18 U.S. sites. Participants must not carry known mutations for autosomal-dominant AD or frontotemporal dementia. Researchers will follow controls for two years, impaired participants for four, collecting PET and MRI data, cerebrospinal fluid and blood, and administering cognitive and neuropsychologic tests.

LEADS began enrolling in 2018 and expected slow enrollment over three years because EOAD is rare, and COVID slowed things down further, Apostolova explained. Complicating the issue, 25 percent of those who were recruited tested negative for amyloid. These early onset non-AD volunteers came as a surprise to the LEADS investigators. They decided to call them EOnonAD and keep them in the study.

At AAIC, Dustin Hammers of Indiana U presented the baseline characteristics of the cohort (Hammers et al., 2023). As of June 2022, researchers had enrolled 89 controls, 212 people with clinically diagnosed EOAD, and 70 with EOnonAD. Participants were in their mid- to late-50s on average, half were women, 86 percent Caucasian.

At baseline, the EOAD group had worse memory scores than the EOnonAD group, averaging 22 on the MMSE versus 25.5 for the latter. Specifically, they did worse on episodic memory, executive function, and attention. These differences held true after accounting for the severity of global cognitive decline, age, sex, and years of education.

APOE genotype seemed to play a big role. Compared to EOnonAD participants, five times as many people with EOAD were APOE4 homozygous. Half as many had an E2 allele. In the EOAD group, 54 percent carried an APOE4 allele. In EOnonAD and controls, 41 percent did. “We were surprised by the high level of E4 heterozygosity in these two groups,” said Hammers.

What is EOnonAD? The LEAD investigators suspect an FTD-like disease, because these participants had more neuropsychiatric symptoms than their EOAD counterparts. In Amsterdam, Polsinelli reported that they were more apathetic and irritable, had less impulse control, and took more mood stabilizers at baseline (Polsinelli et al., 2023). “Although affective symptoms were common in all early onset AD cases, they were more so in EOnonAD,” she said.

In the EOnonAD group, 62 were not diagnosed with PPA, PCA, or non-amnestic dementia. Some of them had cognitive, fluid marker, and imaging characteristics of FTD. Hee Jin Kim, a visiting professor at Indiana U from South Korea’s Sungkyunkwan University, reported that some scored poorly on executive function, visuospatial, and speed/attention tasks, had high CSF and plasma levels of the neurodegeneration marker neurofilament light, and marked atrophy in their frontoparietal lobes.

What Does Genetics Say?

Genotyping, too, suggested an FTD component to EOnonAD. Kelly Nudelman of Indiana U used whole-exome sequencing in search of known pathogenic mutations. In the EOnonAD sample, two carried pathogenic variants in progranulin (GRN), one in MAPT, and two had expansions in C9ORF72. The same search in the EOAD group netted three participants carrying pathogenic PSEN1 variants.

Genetic screening was not an enrollment criterion in LEADS, hence these eight people's genotype status was determined after they had had baseline data collected. They were subsequently excluded from further data analysis and referred to the ALLFTD Study or the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network. No other FTD or ADAD mutation carriers have turned up since, according to Apostolova.

Some other genetic variants already appear to be involved. One person with EOAD and one with EOnonAD carried a variant in the sphingolipid hydrolase gene SMPD1; variants in this gene cause Niemann-Pick’s disease in homozygous carriers. Fifteen people with EOAD and two with EOnonAD carried a dominant pathogenic mutation in the Parkinson’s risk genes GBA or LRRK2. Another six, four EOAD and two EOnonAD, had a recessive variant in a copy of one of three other PD genes—PRKN, PARK7, or PRKRA.

“In a small subset of LEADS cases, the SMPD1 and PD variants may contribute to overall risk for early onset AD, without necessarily being the sole cause,” Nudelman concluded. Strangely, at baseline, only two PD variant carriers had motor symptoms—tremor or slow gait—though nine had peripheral neuropathy, REM-sleep behavior disorder, or other non-motor signs of PD.

Still, most EOAD and EOnonAD cases could not be explained by known pathogenic variants in genes related to neurodegenerative diseases. Two AD risk variants in TREM2, R47H and R62H, turned up in the cohort, but were as prevalent in controls as in symptomatic participants. “We think EOAD is enriched with novel genetic risk factors that might inform our understanding of disease mechanisms and identify novel pathways and drug targets,” Rabinovici wrote to Alzforum (comment below).

Clues from Imaging

Volumetric brain scans revealed differences between EOAD and EOnonAD. Alexandra Touroutoglou, MGH, spotted a pattern whereby the posterior cingulate cortex, lateral temporal cortex, posterior temporal lobe, inferior parietal lobe, and precuneus were smaller in EOAD than in controls. In contrast, EOnonAD participants had no signs of cortical degeneration. This atrophy signature distinguished EOAD from controls and from EOnonAD more accurately than did scanning for the typical atrophy pattern seen in people with LOAD (Dickerson et al., 2009). “The LOAD signature captured atrophy less well than our new EOAD signature. This supports the use of a measure tailored to EOAD, especially to detect small longitudinal changes, as might be expected from disease-modifying therapies,” Touroutoglou said (image below).

EOAD Signature. Nine cortical regions withered in people with EOAD (top), but not in EOnonAD (bottom). [Courtesy of Alexandra Touroutoglou, Massachusetts General Hospital.]

Greater atrophy of the EOAD signature regions correlated with poorer scores on the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) and MMSE. Touroutoglou will follow this cohort and look for different signatures in subtypes, such as PCA and PPA.

Comparing amyloid plaque and neurofibrillary tangle pathology between EOAD and EOnonAD, UCSF’s Renaud La Joie saw that, on baseline PET, all EOnonAD participants were amyloid-negative and most were tau-negative. In contrast, everyone with EOAD was amyloid-positive, and 90 percent were tau-positive (see image below). Plaque and tangle load varied greatly in EOAD, but more amyloid generally tracked with more tangles.

Pretty Separate. EOnonAD participants (orange) were amyloid-negative (x-axis) and most were tau-negative (y-axis). Most people with EOAD (black) were amyloid-positive, and varied greatly in their tangle loads. [Courtesy of Renaud La Joie, University of California, San Francisco.]

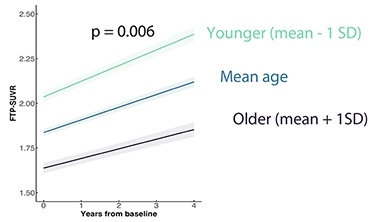

What might influence tangle load? Age at onset showed a dramatic link. Compared to people who became symptomatic in their mid-60s, people for whom this happened in their late 40s or early 50s had more cortical tangles at the baseline point of the LEADS study, and for 17 who had a follow-up scan 3.5 years later, they accumulated additional tangles faster if their age at onset was earlier (see image below). Daniel Schonhaut, also at UCSF, predicted that a 55-year-old person with EOAD would amass tangles twice as fast as someone a decade older when all other demographics matched, even if they had a similar tau load on their first scan.

Why? Perhaps tau aggregates more rapidly in younger brains. Previously, scientists correlated seeding activity of tau in brain extracts with AAO, with seeds from younger people being more aggressive (Jun 2020 news). Rabinovici thinks stronger network connectivity in younger people might also play a role. “If tau spreads trans-synaptically, the higher levels of neocortical activity in young patients may provide many more neuronal pathways for tau to spread,” he hypothesized.

Hammers found that 45- to 50-year-olds with EOAD had worse memory, visuospatial function, and attention than their older counterparts, suggesting that earlier onset signals more severe disease. This phenomenon matches prior findings in LOAD. People who developed AD between ages 65 to 74 dropped 2.0 points annually on the MMSE, while those who first showed symptoms over age 75 slipped 1.4 points per year (Stanley et al., 2019). “Age of onset should be considered a continuous variable, as the association between earlier onset and worse disease progression doesn’t start or stop at age 65,” La Joie said.

Age at onset did not influence baseline amyloid burden or amyloid accumulation over time.

Getting Worse Faster. People whose EOAD began in their late 40s to early 50s (green) had higher tangle load at the LEADS baseline scan and accumulate tau faster than those whose disease began in their early 60s (navy). [Courtesy of Renaud La Joie, University of California, San Francisco.]

Digging deeper into how tau aggregates in EOAD, Schonhaut found that, at baseline, tangles were primarily in the basal-lateral-temporal lobe, parietal association cortex, and mid-frontal gyrus. Over an average of three years, every region except the amygdala accumulated tangles, with the frontal, temporal, lateral, and occipital lobes amassing them quickest. Regions in the first three were part of the EOAD atrophy signature Touroutoglou identified.

Wondering how LEADS baseline characteristics other than age related to tau pathology, Schonhaut looked at sex, amyloid burden, CDR-SB score, and APOE genotype. Only the latter stood out. Over their follow-up, homozygous APOE4 carriers accumulated tangles twice as fast as noncarriers, even after accounting for their baseline amyloid PET load. Scientists are just beginning to appreciate how ApoE4 worsens tau pathology through Aβ-dependent and -independent pathways (Feb 2023 news; Jul 2022 news; Yamazaki et al., 2019).

As for amyloid accumulation, it is strikingly similar in EOAD and LOAD. When UCSF’s Ganna Blazhenets looked at this question, she did not notice this at first, because people with EOAD had more baseline amyloid yet added plaques more slowly than their LOAD counterparts in ADNI. However, Blazhenets realized that EOAD participants were, on average, farther up their amyloid staging curve than ADNI participants.

“Patients with EOAD face a longer path to diagnosis,” Rabinovici said. “Clinicians often don’t have AD on their radar because of the patient’s young age and atypical presentation, often with executive functioning, language, or visuospatial problems rather than memory issues.” Younger people also have high brain reserves and few co-pathologies, enabling them to tolerate a high amyloid burden before showing symptoms, he added. In fact, Blazhenets found that EOAD and LOAD participants with similar baseline amyloid loads accumulated plaques at the same rate (see image below).

Cut From Same Cloth? Amyloid accumulation tends to be detected at different time points in early and late-onset AD (top), since EOAD is often diagnosed at a later stage. When compared at the same baseline amyloid load (bottom left), EOAD and LOAD had the same accumulation rates in a linear mixed-effects model (bottom right). [Courtesy of Ganna Blazhenets, University of California, San Francisco.]

Given that, Blazhenets calculated that the average 75-year-old person in ADNI became amyloid-positive at age 52, while the average 59-year-old in LEADS had turned positive at age 32.

Being amyloid- and tau-negative and unlikely to carry APOE4, people with EOnonAD resemble another mysterious group with suspected non-Alzheimer's pathophysiology. Remember SNAP (Sep 2015 news)? These people have biomarkers of neurodegeneration, yet can be cognitively normal, whereas EOnonAD means dementia. “Technically, some of the EOnonAD individuals in LEADS would likely fall in the SNAP category,” Polsinelli said.

Fluid Biomarkers

If amyloid deposition in EOAD parallels that of LOAD, how about CSF and blood markers? At baseline, they do, too, according to Jeff Dage at Indiana U. Compared to controls, EOAD participants not only had low CSF Aβ42/40 ratios and high CSF p-tau181, t-tau, and NfL, but also abnormal reads of other markers of neuronal health, such as presynaptic protein SNAP25, the postsynaptic protein neurogranin, and the neuronal calcium sensor Vilip1. Only NfL consistently correlated with worse cognition as per CDR-SB, ADAS-Cog1, or MoCa (Dage et al., 2023).

In EOnonAD participants, CSF NfL was slightly up over controls, indicating some neurodegeneration. All other markers were normal, in keeping with a non-AD etiology.

Plasma biomarkers told the same tale. Paige Logan, in Apostolova’s lab, reported that EOAD baseline p-tau231, NfL, and GFAP were high and correlated with more tangles, but not plaques, while an uptick in NfL came with cortical gray-matter thinning. Ralitsa Kostadinova in the same lab found that, in EOAD, these three markers tracked with worse scores on the ADAS-Cog13, MoCA, MMSE, and CDR-SB.

In EOnonAD, only plasma NfL and GFAP were up, and correlated with cognitive decline.

Notably, marker levels differed by sex. Sára Nemes in the Apostolova lab detected more NfL and GFAP in the blood, and more p-tau181, t-tau, neurogranin, and Vilip1 in the CSF of women with EOAD than in blood and CSF from men. Even women with EOnonAD had higher levels of plasma GFAP than men, suggesting that these sex differences occur regardless of amyloid positivity. Nemes thinks this reflects worse pathology or neurodegeneration in women.

“This study provides the first comprehensive analysis of fluid biomarkers in sporadic EOAD. It can inform clinical trial designs that incorporate such markers in patient selection or as endpoints,” Dage said.

LEADing the Way

Apostolova said that as of July 2023, LEADS had enrolled 99 out of 100 cognitively normal controls, 361 people with EOAD, and 112 with EOnonAD. Hammers expects the study to finish enrolling by this fall once it has included 400 EOAD cases. In May 2023, five research papers and a commentary on data generated by LEADS appeared together in a special issue of Alzheimer’s & Dementia. It will contain 11 manuscripts total.

LEADS is set to add five international study sites: University College London, Vrije University Medical Center in Amsterdam, Lund University in Sweden, Sant Pau Memory Center in Barcelona, and Fleni, a nonprofit neurological hospital in Buenos Aires. This is to establish a global network for future cohort studies and, ultimately, clinical trials for EOAD. “The first round of LEADS is observational to optimize the planning of trial outcomes, with the goal of renewing the study to add trial units, like DIAN-TU,” Rabinovici wrote.—Chelsea Weidman Burke

PET tracers that illuminate α-synuclein in the brain have been hard to come by, but scientists may be getting closer. According to a study published August 3 in Cell, an 18F- tracer developed at Emory University, Atlanta, binds to α-synuclein aggregates in human Parkinson’s disease brain samples, in mouse models of synucleinopathy, and in nonhuman primates. Crucially, it does so while shunning Aβ plaques or tau tangles, which commonly co-occur with Lewy bodies. Led by Keqiang Ye, now at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Shenzhen, the study used cryo-electron microscopy to unveil the structural details of the tracer’s specific liaison with α-synuclein. 18F-F0502B joins a growing field of candidate tracers, including three presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, held July 16-20 in Amsterdam. One, made by AC Immune, binds to α-synuclein aggregates when they are highly concentrated in the brain, including in people with multiple system atrophy and in a genetic form of PD. The company’s other up-and-coming tracer candidate holds promise in latching onto the smaller inclusions that predominant in the PD brain. Another, made by Merck, bound synuclein in mouse models of PD.

“We are on the cusp of having a selective α-synuclein PET tracer that performs well in Parkinson’s disease,” said Jamie Eberling of the Michael J. Fox Foundation, which contributes funding for several ongoing efforts to develop the tracers, including AC Immune and Merck’s.

A PET ligand for α-synuclein would help immensely with diagnosis and prognosis of synucleinopathies, and with recruitment and monitoring in clinical trials. Yet, suitable tracers have eluded the field for years, due to their subpar affinity for α-synuclein within the brain, as well as off-target binding to other types of aggregates, including Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Making matters worse, α-synuclein deposits in the brain can be dwarfed by other protein inclusions. In a landmark for the field last year, AC Immune’s 18F-ACI-12589 detected α-synuclein aggregates in people with multiple system atrophy, but failed to label inclusions in people with other synucleinopathies, including PD (Mar 2022 conference news).

In their hunt, co-first authors Jie Xiang, Youqi Tao, and Yiyuan Xia and colleagues took hints from compounds known to bind and block α-synuclein oligomerization, including molecules with catechol groups, such as dopamine and its derivatives. After screening an initial batch of 23 commercially available compounds for binding to preformed, recombinant α-synuclein fibrils, the researchers ran more extensive screens with derivatives of the top hits. F0502B came out on top. This molecule bound to α-synuclein deposits within brain sections of mice expressing A53T mutant human α-synuclein, but not to Aβ plaques or tau tangles in AD mouse models. F0502B also latched onto α-synuclein in brain sections from people with multiple system atrophy (MSA), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and PD, but far less so to Aβ plaques or tau tangles in AD brain samples. Notably, the molecule, as well as its fluorinated form, 18F-F0502B, bound to α-synuclein from PD or DLB brain sections more tightly than it did to recombinant α-synuclein fibrils.

Path to PET. Chemical candidates, including dopamine derivatives, were screened for specific binding to α-synuclein fibrils (1). Top candidates were further tested in mouse models and in human brain tissue (2). Finally, structure of the α-synuclein/tracer complex was determined, and 18F-F0502B was tested in nonhuman primates (3). [Courtesy of Xiang et al., Cell, 2023.]

To understand how F0502B interacted with α-synuclein fibrils, the researchers turned to cryo-electron microscopy. High-resolution electron density maps revealed the tracer nestled into a deep groove along the surface of recombinant α-synuclein fibrils, which comprised stacked pairs of α-synuclein protofilaments. F0502B filled this binding cavity, stacking along the fibril axis in parallel (image below). While recombinant α-synuclein fibrils are distinct from the “Lewy fold” structures identified in brain samples from people with PD, Parkinson’s disease dementia, and DLB, which are collectively distinct from the fold α-synuclein takes in people with MSA, amino acids forming the F0502B binding pocket are also involved in the Lewy fold (Jul 2022 news). In cryo-EM, this fold is typically occupied by unidentified, nonprotein molecules (Mar 2020 conference news). Further, Ye told Alzforum that only a quarter of the fibrils identified in PD brain samples twisted into the Lewy fold, suggesting substantial structural heterogeneity in fibrils even within a single person. He said his group will discern the structure of tracers in complex with brain derived fibrils.

Finding Fibrils. Cryo-EM image (left) and structural diagram (right) of recombinant α-synuclein fibrils reveal F0502B (orange) binding within a groove formed by stacked pairs of α-synuclein protofibrils. [Courtesy of Xiang et al., Cell, 2023.]

Robert Mach of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia commended the researchers for solving the structure of their tracer in complex with α-synuclein fibrils. He noted that although recombinant fibrils are structurally distinct from those found in the brain, several small-molecule binding sites may be common across fibril isoforms (Hsieh et al., 2018). F0502B binds one of these sites, he said. Still, he thinks one potential concern for F0502B is its dependence on a specific tyrosine residue—Y39—for binding. This residue is a well-known hot spot for phosphorylation and nitration, either of which could influence the structure of the binding pocket.

The scientists put their tracer to the test in rhesus macaques. First, they injected into the striatum preformed, recombinant α-synuclein fibrils, or an adeno-associated virus encoding human A53T-α-synuclein. Eighteen months later, dopamine transporter (DAT) scans of the monkeys revealed substantial nigrostriatal degeneration, akin to that in PD. After infusing the tracer, the researchers found scant retention within the brains of controls, but a significant signal from monkeys burdened with synucleinopathy.

With a standard uptake value ratio of around 0.7, 18F- F0502B may not pass muster as a clinical PET tracer. Rather, Mach views it as a great starting place to make analogs. “We know that very small changes in structure can have a large influence on how these molecules perform in PET imaging studies,” he said. “It is highly possible that a close structural analog could work much better.”

Eberling agreed, noting that the tracer could benefit from further optimization, including improved brain penetrance.

Still, Ye said that although next-generation tracers are under investigation, 18F-F0502B is being tested in people with PD, DLB, and MSA. Braegen Pharmaceuticals, Ltd., a company in Shanghai co-founded by Ye, sponsors development.

Signaling Synucleinopathy. PET scans display 18F-F0502B retention in macaques previously injected with α-synuclein PFFs (bottom left panels) or with AAV-A53T-α-synuclein (right) but not substantially in controls (top left). [Courtesy of Xiang et al., Cell, 2023.]

18F-F0502B joins a handful of other up-and-coming α-synuclein ligands. At AAIC, Francesca Capotosti of AC Immune updated the audience on 18F-ACI-12589, which the company had previously reported to work in people with MSA, but not in other synucleinopathies. Since then, the Capotosti and colleagues, in collaboration with Oskar Hansson at Lund University, Sweden, have scanned more participants, including five with AD, three with PSP, and three with ataxia, as well as 23 with a synucleinopathy. Of the latter group, eight had PD, 13 MSA, and two DLB. For the most part, their initial conclusions held, in that substantial uptake in the brain was seen only in people with MSA. Was the tracer’s penchant for α-synuclein in MSA due to the protein’s conformation, or concentration?

To chip away at this question, the researchers infused the tracer into people with genetic PD or DLB caused by a duplication in the α-synuclein gene. These tend to have a higher burden of α-synuclein pathology relative to people with other forms of PD. Lo and behold, Capotosti did observe ACI-12589 uptake in disease-relevant brain regions, supporting the hypothesis that a high concentration of α-synuclein deposits is needed for them to be detected in the scanner, and that differences in fibril conformation do not explain the tracer’s differential uptake in MSA versus other synucleinopathies. In other words, it’s all about the amount of synuclein, Capotosti said. In support of this idea, 18F-ACI-12589 tracer uptake increased in monkeys after they were inoculated with AAV-A53T-α-synuclein.

Mach has a different interpretation. To his mind, conformational differences in α-synuclein fibrils are still likely to play a strong part in the differential performance of the tracer. Based on screening hundreds of α-synuclein-binding compounds, he said he would be surprised if one worked across all synucleinopathies. “We have radioligands specific for PD, and some for MSA, but not any that bind both,” he said. His group is developing separate tracers for each.

Determined to find a PET agent that can work for PD, AC Immune scientists have developed a new crop of tracers with a higher affinity for α-synuclein aggregates. The top contender, ACI-15916, binds α-synuclein with a fourfold higher affinity than its predecessor. In brain sections from people with PD, the new tracer appeared to detect very small inclusions of α-synuclein, as well as Lewy body neurites, whereas ACI-12589 only latched onto larger inclusions. So far, PET scans in monkeys suggest that the new tracer looks hopeful for clinical studies, Capotosti said.

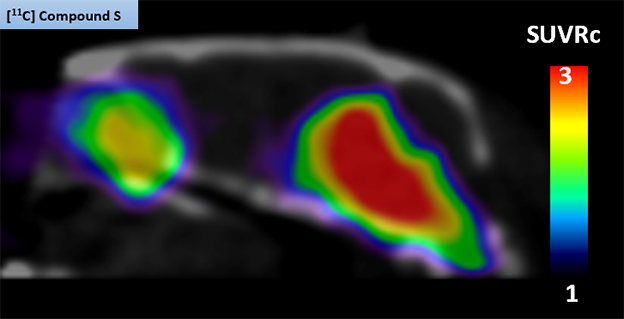

Idriss Bennacef presented the results of Merck’s quest. He cited low target concentration as the biggest hurdle to success. Merck screened its candidates using brain homogenates from people with PD. Provided by Banner Health, the samples were “clean,” in that they were devoid of Aβ plaques or tau tangles, Bennacef emphasized. Its lead compound—11C-MK-7337—bound tightly and specifically to α-synuclein aggregates in brain sections from people with PD, as well as in A30P-α-synuclein transgenic mice. In PET scans, the tracer lit up regions of the mouse brain that also bound α-synuclein antibodies (image below).

Mouse PET. The 11C-MK-7337 tracer shone brightly in the midbrains of A30P transgenic mice, but not in wild-type mice (not shown). [Courtesy of Idriss Bennacef, Merck.]

Alas, the tracer did display some off-target binding in the cerebella of rhesus macaques, raising uncertainties how it will perform in people, Bennacef said. Ongoing clinical studies aim to find out, he said.—Jessica Shugart

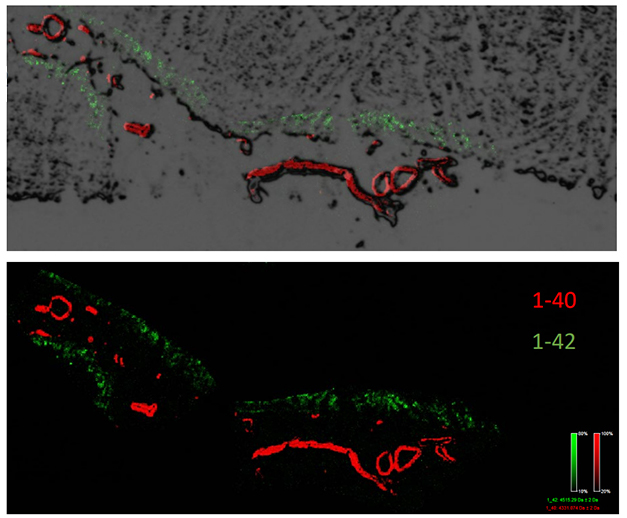

Can scientists who study Alzheimer’s disease find a solution to ARIA? These amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, which reflect brain edema, microbleeds, and occasionally large brain bleeds, have been associated with some deaths in clinical trials. At the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, held July 16-20 in Amsterdam, scientists discussed the latest data on what causes ARIA.

They homed in on an inflammatory reaction to cerebral amyloid angiopathy. CAA experts noted that ARIA-E resembles CAA-related inflammation, a rare and serious condition caused by auto-antibodies to Aβ. In a plenary talk, Cynthia Lemere of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, sketched out a possible mechanism, suggesting that anti-amyloid antibodies may bind vascular amyloid, triggering the complement cascade to attack cerebral blood vessels. This would punch small holes, leading to fluid leakage and microhemorrhages.

Lemere and other speakers proposed therapeutic targets that might blunt the severity of ARIA, while highlighting the need for biomarkers of CAA to aid in prognosis and patient management (see Part 7 of this series). Pharma scientists noted that this is an active area of investigation at their companies, as well, with ongoing efforts to develop algorithms and blood tests to predict and better detect ARIA. “I’m hopeful we will be able to find a way around ARIA,” Lemere said in Amsterdam.

Complement As Hatchet Man. According to a new hypothesis, anti-amyloid antibodies (light blue) bind to vascular amyloid and trigger the complement cascade, prompting the membrane attack complex to form (dark blue), which damages blood vessels. [Courtesy of Cynthia Lemere and Maria Tzousi Papavergi.]

Vascular amyloid is common in AD. In Amsterdam, Roxana Carare of the University of Southampton, U.K., described how soluble Aβ in the parenchyma normally gets flushed out of the brain along blood vessels, draining into the basement membrane that packs the vessel wall. Excess Aβ can become trapped there, clogging the plumbing and forming CAA. White matter, which has fewer vessels and drains solutes more slowly than gray, is particularly vulnerable to this phenomenon. In postmortem analysis of brains that had CAA, fluid buildup can be seen in the perivascular space around white-matter vessels, damaging vascular architecture, Carare noted.

White Matter at Risk. Vascular amyloid (yellow) clogs leptomeningeal arteries and penetrating arterioles. Vascular damage (green) tends to be worse in white matter, which has slower blood flow. [Courtesy of Roxana Carare and Roy Weller.]

What happens during immunotherapy? Carare believes antibody therapy worsens the blockage, because antibody-antigen complexes become stuck in the already-obstructed basement membrane. In people immunized with Elan’s active vaccine AN-1792, the first attempt at immunotherapy 20 years ago, postmortem analysis revealed a worsening of CAA, along with damaged white matter (Boche et al., 2008).

Is Complement to Blame?

Lemere focused on how the innate immune system might contribute to ARIA. Praveen Bathini in her group investigated the effects of immunotherapy in 16-month-old APP/PS1 mice expressing human APOE4. These mice develop extensive vascular amyloid. Treating them for 15 weeks with 3D6, the mouse forerunner of the anti-amyloid antibody bapineuzumab, left cerebral vessels coated with the complement proteins C1q and C3. These vessels sprang leaks, leading to many microhemorrhages. In mice treated with a control antibody, vessels remained intact, as well as free of complement activation.

Antibodies Attract Complement. In amyloidosis mice treated with the 3D6 antibody (top), but not in those that receive an isotype control antibody (bottom), vascular amyloid (blue) in cerebellum (left) and meninges (right) becomes coated with complement protein C1q (red). The antibodies also attract activated microglia (green) and macrophages (gold). [Courtesy of Cynthia Lemere and Praveen Bathini.]

Lemere noted that after a patient has received an infusion of therapeutic antibodies, i.e., a big bolus entering their veins, these circulating anti-Aβ antibodies encounter and bind vascular amyloid first. She thinks these antibodies may get tagged by C1q, which recruits C1r and C1s, forming the C1 complex right there at the cerebral vessel wall. This complex would activate the classical complement cascade, producing C3a and C5a, and eventually resulting in formation of the membrane attack complex C5b-9. The complex pokes holes in cells, in this case along the blood-brain barrier, resulting in leakiness and microhemorrhages. She believes this may be the mechanism by which anti-amyloid antibodies give rise to ARIA-E and -H (see image at right).

In addition, complement proteins C3a and C5a likely activate microglia in the area, triggering vascular inflammation, Lemere said. Other talks in Amsterdam hinted at a microglial contribution, as well (see below).

If the complement cascade does trigger ARIA, then interrupting it, for example with antibodies directed against C1s, might halt this calamitous process. However, Lemere cautioned that therapies would have to be precisely directed, and brief, so as not to leave people immunocompromised. For example, while inhibiting C5 would disrupt the membrane attack complex, it would also hobble the body's essential antimicrobial defenses. C1q itself would also be a tricky target, because it promotes essential cellular function, such as differentiation, migration, and survival. Nonetheless, the complement cascade offers myriad targets, and Lemere said her group is exploring several of them.

These data caught the eye of pharma, with Rachelle Doody at Roche calling the findings an exciting lead. Roche is using data from its gantenerumab trials to model possible mechanisms of ARIA (Aldea et al., 2022).

Myriad Targets. The complement cascade is complex, affording many points where therapeutic interventions could be aimed (red stars). [Courtesy of Garred et al., 2021.]

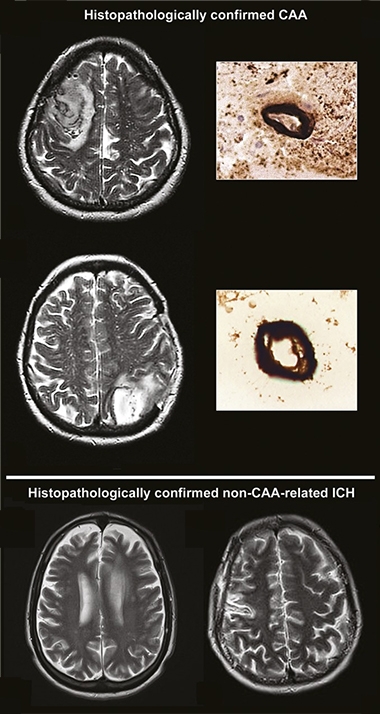

Is ARIA Treatment-Induced CAA-ri?

Others at AAIC elaborated on the links between ARIA and CAA-related inflammation (CAA-ri). Steven Greenberg of Massachusetts General Hospital, an expert on CAA, noted that they look suspiciously similar on MRI scans. Both conditions cause headaches and seizures. Both CAA-ri and ARIA tend to occur in APOE4 carriers, who have more vascular amyloid. Like ARIA, CAA-ri can trigger microbleeds, or occasionally larger hemorrhages. Most tellingly, CAA-ri events are associated with endogenous anti-amyloid antibodies, which peter out as the condition resolves (Kinnecom et al., 2007; Zedde et al., 2023). “ARIA-E is iatrogenic CAA-ri,” Greenberg concluded in Amsterdam.

Fabrizio Piazza of the University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy, linked Alzheimer’s to CAA-ri. He showed case studies of four patients with CAA-ri. Two, who were also positive for AD biomarkers, had more microglial activation, as seen by TSPO PET, in brain areas showing edema. The other two did not. With corticosteroid treatment, this microglial activation waned along with the edema and Aβ autoantibodies (Piazza et al., 2022). The data suggest there may be a heightened inflammatory response to CAA in the context of AD pathology, due to the disassembly of parenchymal plaques that floods clearance pathways with soluble Aβ, Piazza told Alzforum.