Aducanumab: Will Appropriate-Use Recommendations Speed Uptake?

Quick Links

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval of Biogen and Eisai’s anti-amyloid antibody aducanumab on June 7 left many questions unanswered, including how to use the drug in clinical practice. Since then, a group of Alzheimer’s researchers led by Jeffrey Cummings at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, have tried to fill the gap. They formulated appropriate-use recommendations (AUR) for identifying, treating, and monitoring patients who would most likely benefit. On July 27, at this year’s Alzheimer’s Association International Conference from July 26–30 in Denver, Cummings and a panel of experts outlined the AUR and addressed questions and concerns in a series of three panel discussions.

- Appropriate-use recommendations spelled out for aducanumab.

- They call for at least four MRIs in the first year to monitor ARIA.

- Access to the treatment remains very limited, with few centers providing it.

Researchers and clinicians, who attended the hybrid-style meeting in person or online, welcomed the guidance, saying it helped clarify an overly broad FDA label. Unlike aducanumab's approval, which incited a storm of criticism, there was no controversy about these AUR. Rather, the AAIC audience seemed starved for this guidance, asking more detailed questions about implementing the treatment than the AUR, or speakers, were able to answer. In each discussion session, questions had to be cut off for lack of time.

“The AUR are timely and necessary. They should help with the intended and safe use of aducanumab,” Ron Petersen at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, wrote to Alzforum. Mary Sano at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, agreed. “The experts who prepared the AUR have done a great service for practitioners,” she wrote (full comment below).

Published July 20 in the Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease, these AUR were based on available clinical trial data. They will be revised as real-life and more trial data come in. It is unclear if any medical organizations such as the American Academy of Neurology or the American Geriatrics Society, both of which had come out against approving aducanumab, will adopt them. At the moment, the AUR are merely guidelines.

Confusion over appropriate use may partly explain why the clinical rollout of the new therapy is slow. And with no guarantee that private insurance companies or Medicare will cover the $56,000 yearly price tag (see Part 5 of this series), several large healthcare providers have announced they will not administer the treatment. Some researchers worry that rural areas and underserved communities will have trouble accessing the drug, widening disparities in U.S. healthcare. Biogen is promoting aducanumab to practitioners and directly to the public, with sessions at AAIC targeted to the former, and a controversial ad campaign aimed at the latter. The long-term effects of all this on the development of other AD drugs, including other immunotherapies, remain unclear (see Part 7 of this series).

Who Qualifies for Treatment?

After a fraught process, the FDA granted aducanumab’s marketing license under the agency’s accelerated approval pathway, based on the idea that robust amyloid removal is reasonably likely to produce a clinical benefit over time (Jun 2021 news). The decision unleashed intense controversy, which has not abated (Jun 2021 news series; Alexander et al., 2021). In particular, clinicians were incensed by the FDA’s label, which initially specified only “Alzheimer’s disease” as a criterion for treatment. The agency later narrowed that to people with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia due to AD (Jul 8 Endpoints news). Even so, many issues around proper use of the treatment remain unresolved.

To clarify matters, Cummings joined forces with Paul Aisen at the University of Southern California in San Diego, Liana Apostolova at Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis, Alireza Atri at Banner Sun Health Research Institute in Sun City, Arizona, Stephen Salloway at Butler Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island, and Michael Weiner at the University of California, San Francisco. The panel combed through the trial data to define more specific guidelines for how local clinicians should select patients and monitor their treatment.

So what are the AUR? For a start, the panel recommended that clinicians obtain a detailed medical history, test cognition, and perform a thorough neurological exam as first steps in their evaluation of whether the patient before them might benefit from aducanumab. On this, discussion at AAIC emphasized the importance of listening to patient concerns about memory slippage, and paying attention to change in the patient's cognition rather than relying on group-based screening cutoffs that may be inaccurate at an individual level. “Screening tests aren’t always sensitive enough,” Petersen noted. Atri agreed. “You don’t treat a number, you treat an individual,” he said at AAIC. The Alzheimer’s Association has convened a working group to develop step-by-step guidelines for patient screening, Atri added.

Dorene Rentz at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said that even with these AUR, primary care physicians may have trouble selecting the right patients for aducanumab. “Referral to specialists, including behavioral neurologists, dementia experts, and neuropsychologists, should be required prior to administration of the drug,” she wrote to Alzforum.

The aducanumab trial population was limited to people between 50 and 85 years of age, whose MMSE was 24 or higher. In clinical practice, both these ranges could be broader, the panel suggested. They put no limits on age, and proposed an MMSE of 21, or MoCA of 17, as the lower limit, noting that these scores are statistically indistinguishable from those used in the trials. Other researchers agree that due to differences in education, some people who score this low may still be at an early stage of amyloid accumulation and able to benefit from treatment. As in the trial population, patients could be taking cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine.

As important as whom to treat is whom not to treat, the AUR say. The panel urged that anyone who has cerebral amyloid angiopathy, a blood clotting disorder, or takes anticoagulants should not be on aducanumab, because they are already at higher risk for the brain swelling and microhemorrhages known as ARIA. Likewise, aducanumab is inappropriate for anyone who has had more than four microhemorrhages, or any larger brain bleed.

The panel also recommends that chronic conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease be stable before prescribing aducanumab. Moreover, physicians should rule out other causes for cognitive impairment, including side effects of medication, folate or vitamin B12 deficiencies, vascular dementia, or normal pressure hydrocephalus.

Above all, before prescribing this amyloid-reducing medication, physicians should confirm patients have amyloid plaques in their brains. Given the high concordance between amyloid PET, CSF Aβ42, and even CSF p-tau, this ascertainment can be done by either modality. Because Aβ42 drops in the CSF before plaques show up on PET scans, the panel recommended that, in cases where both are available and only CSF is abnormal, the physician not prescribe aducanumab at that time and instead follow up with another PET scan in one to three years.

What about other neurologic conditions in which amyloid accumulates? The panel recommended against prescribing aducanumab for dementia with Lewy bodies or Down’s syndrome, noting a lack of information on how the antibody would affect these complex conditions. In contrast, they said its use could be considered for autosomal-dominant AD and atypical forms of the disorder, such as posterior cortical atrophy or logopenic aphasia. Even so, patients and their families should be informed about the lack of data on how aducanumab performs in these specific populations.

Managing ARIA—MRIs Galore

A great concern for clinicians is how to manage ARIA. This side effect occurred in 41 percent of clinical trial participants who received aducanumab, compared to 10 percent of those on placebo. Most of this difference came from brain edema, or ARIA-E. Isolated cases of ARIA-H, or microhemorrhages, were equally common on drug or placebo, according to a poster at AAIC by Biogen's Patrick Burkett. The ARIA-E incidence was 35 percent overall.

Notably, ARIA-E was much more common in APOE4 carriers, with an incidence of 42 percent, compared to 20 percent in noncarriers. The panel recommended that physicians discuss with patients and their families the option of getting genotyped for APOE4, but only proceed with that testing if the additional risk posed by an APOE4 allele would be a factor in the family’s decision-making.

Another wrinkle is that the E4 allele may increase Alzheimer’s risk in African-Americans less than it does in Caucasians (Farrer et al., 1997; Jan 2019 news). At AAIC, Gil Rabinovici of UCSF noted that because of the lack of diversity in aducanumab's clinical trial population, no one knows if race affects the risk-benefit analysis for aducanumab treatment in APOE4 carriers. Sudha Seshadri of Boston University bemoaned the lack of information on how aducanumab affects non-whites. “We should strongly advocate for a Phase 3 trial for these underrepresented groups,” Seshadri said.

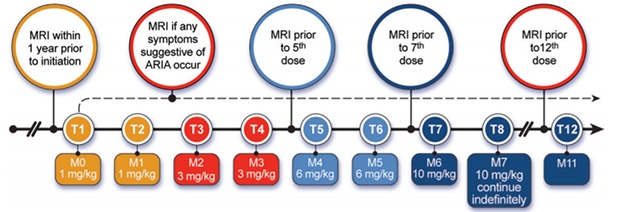

You Better Love That Scanner. The AUR recommend four scheduled MRIs over the first year of treatment, plus an extra scan any time ARIA symptoms crop up. [Courtesy of Cummings et al., JPAD.]

The panel recommends that aducanumab monthly dosing and MRI monitoring should be the same for all APOE genotypes. The FDA label specifies that aducanumab be titrated up over six months, with the first two doses being 1 mg/kg, the second two doses 3 mg/kg, and the third two, 6 mg/kg. At the seventh month and thereafter, physicians would infuse the full dose of 10 mg/kg. About half of ARIA-E events take place during that titration window, and 90 percent within the first year, according to Biogen.

With this in mind, the panel recommended MRI scans at baseline, before the fifth dose, before the seventh dose, and at one year. Ideally, all MRIs should be done at the same center with the same scanning parameters. Physicians should also order an MRI any time the patient develops symptoms suggestive of ARIA, such as headache, confusion, or dizziness. About one-quarter of people with ARIA develop such symptoms. The AUR are strictly medical guidelines; they do not address who will pay for all these scans.

The AUR suggest that the response to ARIA depend on its severity. For asymptomatic cases that look mild on MRI scans, dosing can continue unchanged. In the trials, 6 percent of these cases worsened enough to become symptomatic. For symptomatic cases, or for ARIA cases that look moderate or severe on MRI, physicians should stop dosing and repeat the MRI scan monthly. Once the ARIA-E goes away, or ARIA-H stabilizes, dosing can resume. Ninety percent of ARIA cases resolve within five months, according to Biogen, leaving one in 10 unresolved by that time. About 1 percent of clinical trial participants developed severe symptoms; in such cases, the physician should take the patient off aducanumab permanently, the panel said.

“I found the suggested algorithm around ARIA monitoring and management particularly helpful, as outside of trialists few clinicians will have had experience managing this common adverse effect of the drug,” Rabinovici told Alzforum (full comment below). Kejal Kantarci at the Rochester Mayo Clinic thinks even more guidance is needed. “Because MRI is so critical in the monitoring of patients for safety, we may also need technique-based recommendations on how to best monitor with the available technology and give guidance to neuroradiologists,” she wrote to Alzforum.

When to Stop? It’s Anyone’s Guess

On the question of when to stop treatment, aducanumab trial data offer no guidance. According to the AUR, the decision could be based on what the patient or family want, for example if the side effects or monthly injections become too burdensome to continue, or if the treatment does not seem to be helping.

And how would the patient, family, or physician know if it is helping? The panel members suggested that cognitive and functional decline be monitored with easy-to-administer clinical tools, such as the MMSE, MoCA, AD8, the NPI questionnaire, or FAQ. Importantly, cognitive decline is expected to continue even if aducanumab works, and notoriously variable rates of decline in AD will make it challenging to determine if aducanumab is slowing it down, the panel acknowledged. No guidelines are in place to determine if any such slowing exceeds a minimum clinically important difference (Liu et al., 2021). Many researchers have questioned whether the small benefit seen in the aducanumab trials would be detectable to patients.

For his part, Salloway, who was a site P.I. on these trials, believes it is possible to identify people who stay in the mild stage of AD longer than expected. “There are clear responders,” he said at AAIC. Rabinovici suggested that in the future, effectiveness might be judged by the change in biomarkers associated with cognition and synaptic function. In any case, researchers agree that treatment should be stopped when patients progress to moderate AD, as seen by an MMSE below 20 or a CDR of 2 or more.

What to do once aducanumab has cleared all plaques from the brain? Stop giving the drug, as was suggested by the trial of Eli Lilly's anti-amyloid antibody donanemab (Mar 2021 news)? Biogen's data provide too little evidence on this point, the AUR suggest. “Once significant amyloid lowering has been achieved, it may be possible to reduce the frequency of infusions,” the authors noted.

Uptake Slow, Despite Push from Sponsor

With the question of insurance coverage still wide open, few healthcare systems are offering aducanumab just yet. Two large systems have said they will not administer the infusions at this time: the Cleveland Clinic, based in Ohio, and the Mount Sinai Health System in New York (Jul 15 Fierce Healthcare news). Individual physicians in these systems can prescribe the drug for their patients, who then have to go elsewhere to get the infusions. It’s unclear how many clinicians will sign off on aducanumab use. A survey of 200 primary care physicians and neurologists found that two-thirds doubted the drug’s benefits (STAT news).

As of this writing, about 100 patients across the U.S. have begun to get the treatment (STAT news). Marwan Sabbagh at the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas told Alzforum that he has prescribed aducanumab for some patients, but has had to scramble to find places where they can get the infusions. “I’ve gotten names of doctors around the country who are infusing, but it’s been piecemeal,” Sabbagh noted. One such provider is Amber Specialty Pharmacy, which has 21 locations throughout the U.S. (Businesswire). At the moment, patients who want aducanumab may have to be willing to travel for it.

At AAIC, researchers said the limited access is likely to deepen racial and geographic inequities in healthcare. Many people live in “neurology deserts” without access to specialists, an audience member pointed out. Rentz suggested the increasing acceptance of telehealth could help. “Our clinic is open to consultations from around the world. We do cognitive testing over Zoom,” she said.

The other side of the coin is that only about a quarter of AD cases are diagnosed at the MCI stage, and this rate is even lower for minorities. “Brain health needs to be part of the conversation in primary care,” Kate Possin of UCSF said at AAIC.

Meanwhile, Biogen is promoting aducanumab use to physicians and patients. At AAIC, the company sponsored talks on early diagnosis of MCI using biomarkers, and on how to put together multidisciplinary healthcare provider teams to manage diagnosis and treatment. Targeting consumers directly, the company launched a marketing campaign advising people to seek medical advice for mild memory problems (e.g., see website). One ad in The New York Times drew criticism from Madhav Thambisetty at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, who noted use of misleading statistics (STAT News).

Sabbagh said that every one of his AD patients asks about aducanumab. “The interest from the patient side is very robust. The demand is there. Physician preparedness is not,” he told Alzforum.

Some researchers see answers to some of these questions forthcoming. “I expect there will be an evolution in our patient selection and management when treating patients with aducanumab, and the recommendations may evolve accordingly,” Kantarci said. Rabinovici agreed. “We are at the beginning of a new era of AD therapy, and it will be exciting to see how we refine our approach to patient care as we gain ‘real world’ experience with molecular therapies,” he wrote.—Madolyn Bowman Rogers

References

Therapeutics Citations

News Citations

- Will Insurance Cover Aducanumab? Jury Is Out

- Aduhelm Approval Reverberates Through Research

- Aducanumab Approved to Treat Alzheimer’s Disease

- Do Alzheimer’s Biomarkers Vary by Race?

- Donanemab Confirms: Clearing Plaques Slows Decline—By a Bit

Series Citations

Paper Citations

- Alexander GC, Knopman DS, Emerson SS, Ovbiagele B, Kryscio RJ, Perlmutter JS, Kesselheim AS. Revisiting FDA Approval of Aducanumab. N Engl J Med. 2021 Aug 26;385(9):769-771. Epub 2021 Jul 28 PubMed.

- Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, Hyman B, Kukull WA, Mayeux R, Myers RH, Pericak-Vance MA, Risch N, van Duijn CM. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer Disease Meta Analysis Consortium. JAMA. 1997 Oct 22-29;278(16):1349-56. PubMed.

- Liu KY, Schneider LS, Howard R. The need to show minimum clinically important differences in Alzheimer's disease trials. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021 Nov;8(11):1013-1016. Epub 2021 Jun 1 PubMed.

External Citations

Further Reading

News

- Advisory Committee Again Urges FDA to Vote No on Aducanumab

- Aducanumab Still Needs to Prove Itself, Researchers Say

- FDA Advisory Committee Throws Cold Water on Aducanumab Filing

- Exposure, Exposure, Exposure? At CTAD, Aducanumab Scientists Make a Case

- ‘Reports of My Death Are Greatly Exaggerated.’ Signed, Aducanumab

Primary Papers

- Cummings J, Salloway S. Aducanumab: Appropriate use recommendations. Alzheimers Dement. 2021 Jul 27; PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

Mount Sinai School of Medicine

The experts in the field who prepared the AUR for aducanumab have done a great service for practitioners who are faced with speaking to patients and need to know how to weigh the information that has been provided.

Unfortunately, the information from the trial and from the FDA decision is scant. We have very little information on which to construct these recommendations.

I am so glad that my colleagues were able to step up and summarize what we do know. I hope the company and the FDA will soon become more transparent, and allow us to know critical information such as how the trials were conducted, how many people failed screening and why, and what data was used to allow the FDA to approve on the accelerate basis. Without this information we are truly working in the dark.

UCSF

In the setting of a broad FDA label, the AUR make an important contribution by providing clear guidelines around which patients may be candidates for treatment and, importantly, which clinical features should be considered exclusionary. I found the suggested algorithm around ARIA monitoring and management particularly helpful, as outside of trialists few clinicians will have had experience managing this common adverse effect of the drug.

That said, there are still many outstanding pragmatic and scientific questions about how to implement this new class of drugs in patient care.

We are at the beginning of a new era of AD therapy, and it will be exciting to see how we refine our approach to patient care as we gain “real world” experience with molecular therapies.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.