Past Webinar

Can We (Should We?) Develop “Smart Drugs” to Stave Off Age-Related Memory Loss?

Quick Links

Introduction

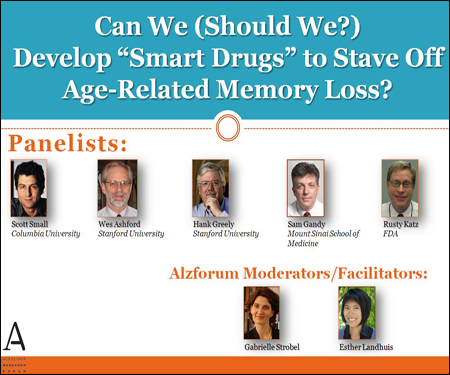

On 26 February 2009, we held a Webinar/Live Discussion with a slide presentation by Scott Small and subsequent panel discussion with legal ethicist Hank Greely at Stanford University, FDA representative Russell Katz, and clinician-researchers John (Wes) Ashford, also at Stanford, and Sam Gandy, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York.

This live discussion began with a Webinar featuring a slide talk with audio provided via a telephone line. Following the talk, the audience moved to a chatroom for Q&A and discussion.

- View/Listen to the Webinar

Click on this image to launch the recording.

Editor's note: On 3 February 2009, NPR broadcast Mind-Enhancers for All, a show based in part on the same Nature Commentary that started this Webinar discussion about drugs for cognitive aging. One of the dozens of comments noted, "In the future I will be thankful for the possibility to stay sharp when my body and mind would otherwise deteriorate." Many comments were critical of the use of drugs by healthy people.

Transcript:

Participants: Carrolee Barlow (BrainCells Inc.), Murali Mohan Bommana (St. John University), Hank Greely (Stanford University), Patricia Heyn (University of Colorado Health Sciences Center), Russell Katz (FDA), Robert McArthur (McArthur and Associates GmbH), Mark McInerney (Visium), Gretchen Reynolds (Freelance Writer), Scott Small (Columbia University School of Medicine), Gabrielle Strobel (Alzheimer Research Forum), Anne Wilson (Anne Wilson Real Estate).

Note: Transcript has been edited for clarity and accuracy.

Carrolee Barlow

Could Rusty comment on the current lack of approved treatments for age-associated memory impairment (AAMI)?

Scott Small

That is an interesting question. Rusty, can you respond to that?

Russell Katz

There aren't any approved treatments for AAMI, but only presumably because industry seems to have abandoned the project. As far as I know, nothing worked, but I don't know exactly how many studies were completed. The regulatory requirements were more or less worked out with the sponsors.

Gretchen Reynolds

I have a question for any of the participants: If exercise becomes an accepted way to decrease the severity of cognitive decline, is it reasonable to have doctors start "prescribing" exercise? And if so, not to be facetious, should running shoes and gym memberships become reimbursable from insurance companies?

Hank Greely

Gretchen, yes, at least in terms of reimbursement. In fact, some health plans are subsidizing exercise-related expenses. (Whether it works in the sense that it gets people who wouldn't exercise to actually do it, consistently and for the long run, as opposed to subsidizing those who would anyway, that remains to be seen.) There is no "prescription," though; there is nothing to order a pharmacist to prepare.

Scott Small

Gretchen, I agree this is reasonable, particularly for old and “frail” individuals who have other comorbidities (i.e., arthritis, heart disease). Thus, I think exercise would be best thought of as “physical therapy” and therefore reimbursable.

Hank Greely

To follow up more with Gretchen, whether or not something is covered by health insurance (or an HMO) is, initially at least, a matter of the insurance contract (affected to some extent by regulatory requirements). An insurer can certainly add that kind of benefit if it wants—and when employers think the benefit will be cost-effective for them, you'll see it offered.

Patricia Heyn

About exercise: we do not have a guideline/protocol in place. Yes, in general, physical activity has been shown to support neuroprotection and enhancement, but what should be the prescription, the dose, intensity, and even mode? There is still much more work to be done in the activity-induced cognitive enhancement research area. We need to study behavior adherence and motivation, as well.

Hank Greely

Rusty, do you see any good way to handle the risks of off-label use? What if lots of teens and 20-somethings were using a drug that had been tested only in people over 50? If a good treatment is developed for memory decline in older people and younger people start using it widely without any clinical trials, I'll be worried about safety.

Gabrielle Strobel

In thinking about off-label use of such future drugs, is this not a broader problem of the FDA's resources to police inappropriate off-label use? Off-label use that draws criticism from clinicians and the Alzheimer’s Association comes up in AD treatment from time to time, but to my knowledge has not prompted action by the FDA.

Robert McArthur

Following up on Dr. Ashfords’s comments: There appears to be a tacit acceptance that magic white powders will magically, or with a little training, “enhance cognitive abilities” that can transform middling intelligence to super bright in a manner analogous to taking steroids to enhance physical abilities. Where is the evidence for such an assumption? The drug industry has been trying for decades now to provide Alzheimer’s patients with such a magic powder and has succeeded only in tweaking memory, attention, and other cognitive processes of such patients. These cognitive enhancing drugs have been tested and characterized using specific testing conditions. Even if one is able to demonstrate a statistically significant improvement in performance in a more general population setting, i.e., during school exams or aptitude tests, what is the evidence that administration of these compounds/drugs will have long-term effects on presumably enhanced cognition?

Gabrielle Strobel

Robert, to clarify: Scott Small's presentation today focused on biological, mechanistic differences between cognitive aging and AD. These would provide the basis for drug discovery and lifestyle intervention. Regarding future anti-cognitive aging drugs, Dr. Katz said that the FDA would require data to show not only that such drugs have statistically significant effects in specific testing conditions, but also that they are clinically meaningful to people. We are not focusing on off-label use of current AD drugs by the young and healthy in this hour. So off-label use of those drugs is a future concern, not the goal. Does that address your concern?

Hank Greely

Gabrielle, I agree that off-label use is not the goal of those developing these drugs, but I don't think it is only a future concern. It is something we should think about—I believe—whenever a new drug is approved that has the potential for substantial off-label use. Unfortunately (I think), the law doesn't give the FDA much control over off-label uses except through regulation of marketing. Robert, the basis for my assessment that there is a "reasonable chance" such things will be developed is the incredible revolution in our knowledge of the human brain. Drugs that significantly enhance cognition may or may not actually come to pass, but they aren't a crazy idea.

Robert McArthur

Having worked for many years on pharmaceutical drug discovery for the treatment of AD, I, too, wouldn't say that it is a crazy idea. However, one does become concerned with the assumption, even within the industry, that our "cognitive enhancers" will do good things not only for the cognitively impaired but also for the normally functioning individual. The effectiveness of these compounds is yet to be shown.

Gabrielle Strobel

Robert, what do you think about aging and age-related decline? Would that seem more acceptable to you? That is really the specific aspect to this discussion today. Rusty, I am chagrined that the system is logging you off. My apologies. We are having a conversation about whether the FDA could use more authority to curtail off-label use where inappropriate. Would you welcome that?

Russell Katz

Gabrielle, I seem to be back for the moment. I'm loath to ask for more authority in this area, because we get into the practice of medicine and that's very problematic from my point of view. I think it depends on each case, but I think primarily our job is to approve drugs that are safe and effective for a particular use, and be truthful in labeling about what we do know and don't know (where appropriate). I think there are many issues that need to be considered before we tread heavily onto the practice of medicine.

Hank Greely

Rusty, that's a wise answer, certainly politically but also prudentially. But it is worrisome when drugs become very widely prescribed (and, when widely available by prescription, become easily accessible on a black market) for people and conditions other than those for which they've been tested. I respect doctors highly (I'm married to one), but I don't trust the country's 800,000 doctors always to do the right thing. I think the FDA might consider requiring, or encouraging, broader testing for drugs where off-label use seems likely. But I know this is tough—in terms of legislative authority and political power.

Gabrielle Strobel

Hank and Rusty, and all, it seems to me simply as a reader of newspaper coverage of these issues, that patients’ and doctors’ not adhering to a drug's label and safety restrictions causes at least some of the public controversies around drugs—unintended side effects, drug withdrawals from market, lawsuits. Given all this, it seems to me that curbing unsafe off-label use would have benefits, certainly with drugs that act in the brain and therefore are of perhaps heightened concern. No?

Russell Katz

Gabrielle, I can’t say what folks will do in this regard. I agree that doctors may prescribe inappropriately. We certainly spend a fair amount of time encouraging companies to develop drugs for populations that we know will be (or are being) treated off-label. There already are some provisions in the law that allow us to require studies. For example, we can require studies in pediatric patients if the disease for which it is approved in adults exists in kids. And recently the law did give us the authority to study certain conditions if we become aware of a new safety signal (this is very recent), so we do have some authority that we didn't previously have, but this is quite new.

Gabrielle Strobel

Hank, you raised the issue of fairness and access with such drugs in your audio presentation—is it much different than the broader issue of privilege in society in general? Wealthier people have advantages in many different arenas already, certainly including health and longevity. Anything specific to this type of drug that strikes you as worth thinking about?

Hank Greely

Gabrielle, that's a great point. The rich can buy lots of cognitive enhancers, like good schools, tutoring, etc. I don't think this is fundamentally different, but it is one more, cumulative unfairness—and, like many things, is probably more addressable before it becomes widespread rather than after. There really are two fairness questions, by the way—the broad, social "rich/poor" or "well insured/poorly insured" fairness issues, and individual fairness issues—in this case, maybe contestants on Jeopardy would be the clearest example, though job performance broadly could be implicated.

Gabrielle Strobel

Scott, can you say anything about the kind of compound discovery based on your dentate gyrus findings that your lab is undertaking?

Scott Small

Gabrielle, we are still in the “preclinical” stages, namely, attempting to identify the molecular defects that “cause” age-related dentate gyrus dysfunction. As I mentioned, one of the lead hits is molecules that relate to histone acetylation. This is potentially interesting because there are a number of available drugs that might correct this problem. We are currently testing to see whether they “rescue” age-related dentate gyrus dysfunction.

Gabrielle Strobel

Scott, it just so happens that our last Live Discussion was about HDAC, and the effects of HDAC inhibitors came up. I wonder, how long in the aging and dementia processes does the separation between the entorhinal cortex and the dentate gyrus hold? As people progress in AD, pathology and volumetric shrinkage spreads to other brain areas. Can one really distinguish based on hippocampal subareas except in the very earliest stages of both processes?

Scott Small

Gabrielle, from a clinical perspective, once AD progresses it actually is not very difficult to distinguish AD from aging. It’s nearly trivial. Although your point is well taken, the anatomical differentiation “game” is most easily played at early stages.

Gabrielle Strobel

I was wondering in terms of developing a cognitive aging drug, how you can make sure that you keep trial groups separate if indeed trials have to be very long. Because having the wrong people (e.g., MCI ”contamination” in your cognitive aging group) in your trial arms might make it harder to get a significant efficacy signal for the drug. On that issue, perhaps high-resolution MRI would be helpful to keep folks with MCI/incipient dementia out of trials? I am saying that because in past MCI trials, clear delineation of the trial arms has been a problem.

Scott Small

I see.... One thing about clinical trials: I do think that treating a “sick cell” will be easier than treating a dead cell. This, as you know, is the great promise of “functional imaging.” Not only distinguishing from aging, but earlier detection of AD, before the onset of rampant cell death.

Gabrielle Strobel

Rusty and all panelists, the drug Alzhemed, which is a derivative of an amino acid sold in health food stores and infant formula, had unapprovable Phase 3 data and was widely considered to have failed formal drug development. It is now being marketed in Canada as Vivimind for exactly what we are talking about today—age-related memory loss. It’s a non-FDA-approved supplement that claims to be scientifically proven to protect memory function. Given this experience, is it not likely that other developers of cognition drugs will opt for this route to the market right away, rather than go through the FDA process, especially if trials for a normal population have to be large and long, i.e., expensive?

Hank Greely

Gabrielle, the dietary supplement loophole (today's "patent medicine," I think) is particularly plausible for enhancement, as dietary supplement makers aren't allowed to make disease claims (treatment of heart disease) but only structure and function claims (improves cardiovascular health). "Improves cognitive performance"/"improves memory" is a classic structure and function claim. So if the molecule involved is found in something that someone, somewhere, sometime, has been eaten as a food, I'd worry about an almost totally unregulated influx of dietary supplement cognitive enhancers...and, in fact, you can already find many on sale at health food stores. The good news, I guess, is that, thus far, they probably don't work.

Gabrielle Strobel

Hank, Rusty, and all, along this vein, there is also a product called Axona by a company named Accera. This started out in regular Phase 1 and 2 trials (see ARF related news story), but rather than moving on to Phase 3 is going to be marketed soon as a so-called “medical food.” Is that basically a middle route between formal drug approval and no regulation at all for a dietary compound with memory function claim? Where basically the FDA grants a safety designation but no efficacy designation, in other words “won’t do harm but not proven to help?”

Russell Katz

These products are foods to be administered under the auspices of a physician intended for specific dietary management of a disease that requires "distinctive nutritional requirements.” This is intended to be a narrowly defined category. The last thing I am is an expert in this area, but it seems that these products have to be foods (i.e., have some nutritive value), and the patients for whom they are intended have to have some problem managing ordinary food. It doesn't appear that products that aren't otherwise foods would qualify as medical foods, and it doesn't look like medical foods can make claims like cognitive enhancement. Dietary supplements are defined specifically in the law, and are allowed to make "structure/function" but not disease claims (e.g., they can say they improve memory, but not that they treat AD), and these claims are not reviewed by the Agency prior to their being permitted. (For more on how the FDA defines and oversees medical foods, go to this website).

Mark McInerney

I have a question for Dr. Katz: There is a high probability that any new "cognitive enhancer" will probably be introduced through a proven regulatory pathway (like the one for adult ADHD). Would a drug featuring a new mechanism, like nicotinics, be subject to a cognitive enhancer-type safety hurdle (i.e., long trials with large numbers)?

Russell Katz

I'm actually not so sure that there is a high probability that a cognitive enhancer would first come in through a more traditional route, but be that as it may, I believe that any compound that came in for such a "cognitive enhancer" in otherwise "normal" people would probably be subject to what Mark refers to as the "cognitive enhancer-type safety hurdle." Certainly, a new mechanism may raise some new issues, but, in general, it's the claim that's being sought (and, of course, the degree of benefit seen), as well as any issues specific to the proposed population, that dictate the safety requirements. Even if the drug is already approved for some indication, if the new proposed indication markedly expands the population that would be exposed to the drug, new safety requirements appropriate to the new claim/population would be imposed (of course, in this circumstance, the previously accrued safety data are likely to be of some use, assuming the population for whom it is already approved bears some likeness to the new proposed population, so that the safety data gained in the old population would be relevant for the new population).

Anne Wilson

Is it fair to assume that these hypothetical drugs will be very expensive or is it an unknown at this point?

Murali Mohan Bommana

Dr. Small, your PowerPoint was impressive. Can age-related obesity be a factor for cognitive impairment or development of Alzheimer’s in the near future?

Russell Katz

Gabrielle, I have to leave; thanks very much, everyone, and sorry I had so much trouble logging on.

Patricia Heyn

I hope we will find more opportunities to further discuss these interesting topics.

Gabrielle Strobel

The software is malfunctioning today and activity is dying down, probably because people get disconnected frequently while trying to type. Argh! I apologize—we’ll trouble shoot the problem. For now, let me thank all of you for your patience, and I'll close today's event. Scott, Rusty, Hank, and all panelists and audience participants, I will be more than pleased to include any closing comments you want to make if you send them to me by e-mail gabrielle@alzforum.org. We will revisit this topic as the research unfolds. Goodbye for now.

Background

Background Text

By Esther Landhuis and Gabrielle Strobel

Last December, a high-powered group of legal, ethical, medical, and cognitive neuroscience scholars raised eyebrows when they argued, in a Nature commentary that the use of cognition-enhancing drugs by healthy people should be considered socially acceptable. First author Henry (Hank) Greely of Stanford University, a leading voice on the legal and ethical implications of innovations in biomedicine, and colleagues furthermore outlined policy suggestions for their safe and effective development as cognitive enhancers. The opinion piece focused on the growing off-label use—primarily though not only among students and academics—of stimulants prescribed for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, but it also mentioned the possibility of a modest memory boost for healthy people from the acetylcholinesterase inhibitors that are widely prescribed for Alzheimer disease. Occasional reports of AD drug use by cognitively normal people have cropped up anecdotally, and a small literature exists on this issue (e.g., Yesavage et al., 2002; Grön et al., 2005; Chuah and Chee, 2008; FitzGerald et al., 2008). The Alzforum set out to get a sense for how commonly AD drugs might be used as enhancers of choice. According to some noted AD clinicians, use of AD medications among the healthy appears rare and limited to short-term benefit.

But out of this conversation emerged a related topic that represents a more relevant and equally challenging discussion for Alzforum readers: that is, should the field develop drugs for the cognitive decline that accompanies “normal” aging? And if indeed this is considered legitimate in a changing society—where people live longer, with high expectations for continued mental acuity and productivity into old age—then how would researchers go about finding such drugs? This, in a sense, is the opposite question: not to give drugs originally developed to treat Alzheimer’s as cognitive enhancers to normal people, but rather to develop drugs specifically to prevent “normal” memory loss as people age.

Decades ago, investigators believed age-related memory loss simply represented early-stage AD. By now, however, converging evidence from studies in people, non-human primates, and rodents has pinpointed brain regions with a differential vulnerability to AD and to non-pathological aging. For instance, within the hippocampus early AD targets the entorhinal cortex, causing neuronal loss there (Scheff et al., 2005; Killiany et al., 2002), whereas normal aging tends to hit a neighboring subregion, the dentate gyrus, much harder than the entorhinal cortex (Chawla and Barnes, 2007). In particular, in December 2008 a team led by Scott Small at Columbia University, New York, identified age-related elevation in blood glucose concentration as a potential culprit underlying age-related memory loss that is distinct from AD (Wu et al., 2008). The work—which combined magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of 240 non-demented elders with follow-up functional MRI studies in monkeys and mice—suggests that maintaining normal glucose levels could help preserve cognitive function in healthy elders. Small’s lab has begun to identify compounds that differentially improve the function of the dentate gyrus and therefore might stem normal age-related cognitive decline.

Suggested questions for discussion:

- Should investigators develop cognition-enhancing drugs to stem a process that occurs “normally” (i.e., aging)? Is this treatment or enhancement? What exactly does “normal” mean in this context?

- On what grounds might such drugs be considered ethical? How would this differ from previous attempts at cognitive enhancement, such as with ampakines and similar drugs?

- What would be the molecular targets of drugs for normal aging?

- Would such drugs benefit people with AD, vascular dementia, or ischemic brain damage, as well, even though they are not the intended target group?

- What is the regulatory stance toward drugs treating cognitive aging?

References:

Greely H, Sahakian B, Harris J, Kessler RC, Gazzaniga M, Campbell P, Farah MJ. Towards responsible use of cognitive-enhancing drugs by the healthy. Nature. 2008 Dec 11;456(7223):702-5. Abstract

Wu W, Brickman AM, Luchsinger J, Ferrazzano P, Pichiule P, Yoshita M, Brown T, DeCarli C, Barnes CA, Mayeux R, Vannucci SJ, Small SA. The brain in the age of old: the hippocampal formation is targeted differentially by diseases of late life. Ann Neurol. 2008 Dec;64(6):698-706. Abstract

References

Webinar Citations

News Citations

- Experts Slam Marketing of Tramiprosate (Alzhemed) as Nutraceutical

- Washington: Shaking Up AD Treatment with Ketone Bodies

Paper Citations

- Greely H, Sahakian B, Harris J, Kessler RC, Gazzaniga M, Campbell P, Farah MJ. Towards responsible use of cognitive-enhancing drugs by the healthy. Nature. 2008 Dec 11;456(7223):702-5. PubMed.

- Yesavage JA, Mumenthaler MS, Taylor JL, Friedman L, O'Hara R, Sheikh J, Tinklenberg J, Whitehouse PJ. Donepezil and flight simulator performance: effects on retention of complex skills. Neurology. 2002 Jul 9;59(1):123-5. PubMed.

- Grön G, Kirstein M, Thielscher A, Riepe MW, Spitzer M. Cholinergic enhancement of episodic memory in healthy young adults. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2005 Oct;182(1):170-9. PubMed.

- Chuah LY, Chee MW. Cholinergic augmentation modulates visual task performance in sleep-deprived young adults. J Neurosci. 2008 Oct 29;28(44):11369-77. PubMed.

- FitzGerald DB, Crucian GP, Mielke JB, Shenal BV, Burks D, Womack KB, Ghacibeh G, Drago V, Foster PS, Valenstein E, Heilman KM. Effects of donepezil on verbal memory after semantic processing in healthy older adults. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2008 Jun;21(2):57-64. PubMed.

- Scheff SW, Price DA, Schmitt FA, Mufson EJ. Hippocampal synaptic loss in early Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2006 Oct;27(10):1372-84. PubMed.

- Killiany RJ, Hyman BT, Gomez-Isla T, Moss MB, Kikinis R, Jolesz F, Tanzi R, Jones K, Albert MS. MRI measures of entorhinal cortex vs hippocampus in preclinical AD. Neurology. 2002 Apr 23;58(8):1188-96. PubMed.

- Chawla MK, Barnes CA. Hippocampal granule cells in normal aging: insights from electrophysiological and functional imaging experiments. Prog Brain Res. 2007;163:661-78. PubMed.

- Wu W, Brickman AM, Luchsinger J, Ferrazzano P, Pichiule P, Yoshita M, Brown T, Decarli C, Barnes CA, Mayeux R, Vannucci SJ, Small SA. The brain in the age of old: the hippocampal formation is targeted differentially by diseases of late life. Ann Neurol. 2008 Dec;64(6):698-706. PubMed.

Other Citations

External Citations

Further Reading

Papers

- Feany MB, Bender WW. A Drosophila model of Parkinson's disease. Nature. 2000 Mar 23;404(6776):394-8. PubMed.

- Haass C, Kahle PJ. Parkinson's pathology in a fly. Nature. 2000 Mar 23;404(6776):341, 343. PubMed.

- Pereira AC, Huddleston DE, Brickman AM, Sosunov AA, Hen R, McKhann GM, Sloan R, Gage FH, Brown TR, Small SA. An in vivo correlate of exercise-induced neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Mar 27;104(13):5638-43. PubMed.

- Pereira AC, Wu W, Small SA. Imaging-guided microarray: isolating molecular profiles that dissociate Alzheimer's disease from normal aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007 Feb;1097:225-38. PubMed.

- Small SA, Tsai WY, DeLaPaz R, Mayeux R, Stern Y. Imaging hippocampal function across the human life span: is memory decline normal or not?. Ann Neurol. 2002 Mar;51(3):290-5. PubMed.

Panelists

-

Scott Small

Columbia University

Scott Small

Columbia University

-

John (Wes) Ashford, M.D., Ph.D.

Stanford / VA Aging Clinical Research Center

John (Wes) Ashford, M.D., Ph.D.

Stanford / VA Aging Clinical Research Center

-

-

Sam Gandy, M.D., Ph.D.

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Sam Gandy, M.D., Ph.D.

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

-

Comments

Stanford / VA Aging Clinical Research Center

1. I believe there is no evidence that any Alzheimer medication helps individuals without dementia. The MCI trials have been negative or showed a preponderance of adverse effects. Under normal and early AD circumstances, neurotransmitters in the brain are carefully balanced to cope with the complexities of the world.

2. Cholinesterase inhibitor medications appear to be severely addictive. Patients go into steep declines when they discontinue these drugs; that is likely due to a reactive super-production in the brain of cholinesterase molecules.

3. Memantine has only been shown to help moderately to severely demented patients, and it can be deleterious in mildly demented patients.

4. There is no long-term objective evidence that the currently available, legal, and widely used cognition-altering drugs—nicotine, caffeine, and ethanol—actually benefit anybody.

5. Before we advocate for the addition of any substance to be added for routine use by any individual, society, or species, there should be extensive evidence of exactly whom it helps, how much it helps, and what the costs and adverse effects are, particularly over very long periods of time.

6. The important direction for drug development is to determine what treatment can benefit a person's life, particularly by stopping a process that has been clearly recognized as deleterious and pathological. In this case, we still need to define the pathological process.

7. To me, treating aging per se does not make sense since aging is just the accumulation of responses to stress over the lifetime of the individual as redundant systems lose their capacity to deal with normal world events. It is the pathological process that occurs more specifically in a single individual or group of individuals that is of interest. Then, the basis of that process can be understood—either genetic or environmental, and steps may be considered to prevent that process from developing.

8. Genetic factors that lead to specific deficits should be understood, and therapies should be developed to mitigate those factors. In my view, a great deal of benefit could be had by further understanding the relationship between the apolipoprotein E subtypes and their relationship to Alzheimer pathology, particularly with respect to how dietary adjustments could delay the development of Alzheimer pathology.

Stanford / VA Aging Clinical Research Center

I have two comments that I still feel need to be clarified with respect to Dr. Small's presentation.

1. The difference between normal and pathological aging is artificial. As long as you are alive, you are surviving. When you are dead, it doesn't matter what you call it.

Four different aspects of aging are studied:

All problems, including mortality, are both pathological and normal aging. Mortality is the most serious problem a living organism can face, natural though it is. Alzheimer disease is actually more closely related to aging than to mortality itself.

For more on the Gompertz-Makeham law, see this article.

For more on how aging theory relates to understanding Alzheimer disease, and how this relationship could aid the development of new AD treatments, see Ashford et al., 2004 [.pdf].

2. As problems develop with age, they need to be addressed in the most cost-efficient means possible. That is what Dr. Katz pointed out is the critical issue in the FDA's decision-making process. But the more data and the longest view of the data possible are important.

�

Memory loss will be a bad disease to live with as we will forget how were living. To cure this, of course some drugs should be develop.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.