Being Bilingual Buffers Against Alzheimer’s by Improving Connectivity

Quick Links

A new study led by Jubin Abutalebi of the Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan, provides a possible explanation for why speaking a second language slows the development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The researchers reported in the January 30 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that bilingual people form stronger connections between some regions of their brains than do monolinguals. These beefed-up networks might allow people to adapt to age-related reductions in brain functions.

“This is a really exciting paper because it’s the first to examine differences in brain metabolism in people who are bilingual,” said Judith Kroll of the University of California, Riverside. Kroll was not connected to the study. “It begins to unpack what it is about language experience [that inhibits AD symptoms], and how [that experience] manifests in the brain,” she told Alzforum. Brian Gold of the University of Kentucky in Lexington, who also wasn’t connected to the research, called it very provocative and interesting. “The study adds evidence that speaking a second language may delay AD by increasing metabolic response in several brain circuits,” he said.

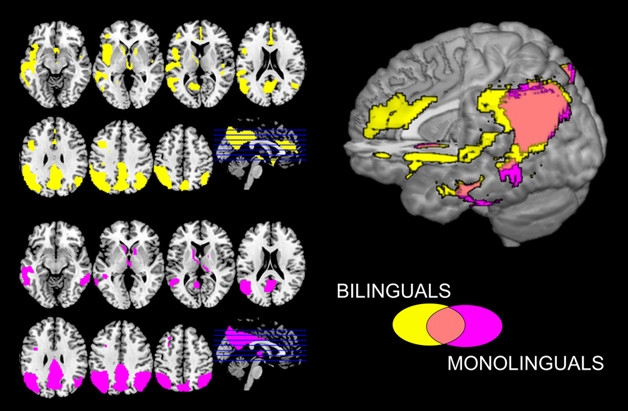

Parli Italiano? Though they perform better in some memory tests, bilingual AD patients have more widespread brain hypometabolism (yellow) than monolinguals (pink). [Courtesy of Jubin Abutalebi and PNAS.]

Bilingual people are known to develop AD four to five years later than do monolinguals. Several studies have shown that speaking a second language from a young age fends off brain and cognitive deterioration late in life (see Nov 2010 news; Jan 2013 news). What is it that protects them from AD? Adding to the mystery, imaging studies have revealed that older bilinguals with AD have more brain atrophy than do their monolingual counterparts (see Jan 2013 news). Researchers have speculated that better connectivity between intact neurons may compensate for this atrophy.

To determine if bilingualism alters brain activity in AD patients, first author Daniela Perani and colleagues compared two groups of patients who had the disease. Forty spoke Italian, while 45 spoke fluent German and Italian. Only patients who were proficient in both languages and had been regularly exposed to them qualified as bilingual for this study. The bilingual patients outperformed their counterparts on tests of short-term spatial and verbal memory and of long-term memory.

The researchers next measured brain activity with FDG-PET, which gauges neuronal metabolic levels by recording the absorption of a radioactively labeled glucose analog (but see Feb 2017 news for a slightly different take). For comparison, the scientists also scanned the brains of healthy people of similar age.

PET scans revealed that in a few brain areas, metabolism was lower in all AD patients than controls (see image above). This weakened activity was more widespread in the bilingual participants, hinting that they had more neurodegeneration than monolinguals. That finding dovetails with results from previous brain atrophy studies. However, in bilingual people, metabolic activity rose in other brain areas, suggesting that they were trying to make up for the damage. This increase was largest in people who were strongly bilingual as defined by frequently using their second language and interacting with other speakers.

Bilingual people also had an advantage when the researchers measured the degree of connectivity in the brain. To do this, the scientists correlated glucose metabolism among different brain regions, focusing on the executive control network, which contributes to decision-making, and the default mode network (DMN), which is active at rest. Both are known sites of AD pathogenesis (see Research Timeline 2004; Aug 2014 news). Perani found bilingual patients had forged stronger connections within both networks than had monolingual patients. For example, the former had tighter links among areas involved in language and cognition, such as the cingulate cortex, the inferior frontal gyrus, the parietal operculum, the insula, and the caudate nucleus. In the DMN, posterior cingulum connected more strongly with the anterior cingulum. The stronger connections may enable bilingual people to better compensate for reduced neural activity as they age. In fact, their findings support the idea that a posterior-anterior shift in connectivity compensates for cognitive decline during normal aging (see Davis et al., 2008).

The results also suggest that the benefits of speaking a second language are so great they outweigh two other factors that would seem to promote AD in that particular group. The bilingual participants had on average two fewer years of schooling than the monolingual patients, and were nearly five years older. “Despite having signs of more neurodegeneration, the bilinguals are better off,” Abutalebi told Alzforum.

However, before all you Anglophones with high school French or German pat yourselves on the back, the upside of a second tongue dwindles if people don’t continue to speak it. “Only those who really use the two languages are protected,” Abutalebi said. He added that he would like to investigate whether refresher courses benefit older people who haven’t kept up.—Mitch Leslie

Mitch Leslie is a freelance writer based in Tucson, Arizona.

References

News Citations

- Research Brief: AD Risk—Do Bilinguals Buy Time?

- Can Being Bilingual Preserve Brain Function?

- Do Astrocytes Blur the PET Signal for ‘Neuronal’ Activity?

- Neural Circuitry Goes Haywire in Both Sporadic and Familial AD

Paper Citations

- Davis SW, Dennis NA, Daselaar SM, Fleck MS, Cabeza R. Que PASA? The posterior-anterior shift in aging. Cereb Cortex. 2008 May;18(5):1201-9. Epub 2007 Oct 8 PubMed.

Other Citations

Further Reading

No Available Further Reading

Primary Papers

- Perani D, Farsad M, Ballarini T, Lubian F, Malpetti M, Fracchetti A, Magnani G, March A, Abutalebi J. The impact of bilingualism on brain reserve and metabolic connectivity in Alzheimer's dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Feb 14;114(7):1690-1695. Epub 2017 Jan 30 PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

National University of Singapore

It would be interesting to study bilingual and monolingual elderly who have normal cognitive function, elevated risk of future dementia, subjective cognitive decline, or mild cognitive impairment, so we will have a complete picture of how bilingualism changes brain plasticity and reserve and the natural history of dementia.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.