Boxing: Study of Human Model for CTE Enters Second Round

Quick Links

Viewed through a scientist’s lens, professional boxing is a series of scheduled, measurable head traumas. In other words, it is a human model for chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Seen this way, the sport offers a unique opportunity to study the natural history of this proposed progressive tauopathy for an understanding of its presymptomatic pathogenesis and progression. Such data can form the basis for treatment studies and for tools that help boxers decide when to retire from the ring. On 30 September 2012, at a research conference on CTE held at the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas, Nevada, Charles Bernick of the Lou Ruvo Center summarized what is known about CTE in boxers and shared early results of his ongoing work with 225 fighters in Las Vegas who have joined a longitudinal biomarker study.

Boxing is the sport that prompted the first phenotypic description of what is now CTE, when the pathologist and Newark medical examiner Harrison Martland coined the term Punch Drunk syndrome (JAMA, 1928;91:1103-1107). The term CTE first showed up in a chapter titled “Punch drunk syndrome: The chronic traumatic encephalopathy of boxers,” that the British neurologist MacDonald Critchley contributed to a 1949 book edited by the French neurosurgeon Clovis Vincent. The current research focus on CTE in the U.S. began with a report on the neuropathology of the former NFL players Terry Long and Mike Webster (see ARF related news story on Omalu et al., 2006).

Epidemiological data on CTE in boxers are sparse, Bernick told the audience in Las Vegas. Some studies put its prevalence among boxers at 17 percent, while others note abnormal brain function in almost all boxers studied. The natural history literature is equally disparate. A predictable course is not yet known. The prevailing estimate is that one-third of cases are progressive, but fighters’ frequent comorbidities such as substance abuse or stroke make that difficult to ascertain. Likewise, some potential risk factors are known—age, number of bouts, number of knockouts, duration of career, ApoE4 status—but those, too, need to be rigorously tested in a natural history study, Bernick said. One particularly fuzzy area is how scientists can measure exposure to cumulative head trauma beyond the bouts and knockouts of known fights. “We do not know what happens in sparring,” Bernick said. “When you ask a fighter if he has ever been knocked out, he’ll say ‘No.’ ‘Have you ever had concussion?’ ‘No.’ ‘Have you ever gotten your bell rung?’ ‘Oh yeah, that happens all the time.’”

In 2011, Bernick started the Professional Fighters Brain Health Study to identify early markers and predictors of CTE. The Nevada Athletic Commission and promoters in town support the study and help spread the word, Bernick said. Ninety-six boxers and 136 mixed martial arts fighters aged 17 to 44—some active, some retired—have joined thus far. Their education level ranges widely from six to 18 years, as does the number of years they have fought professionally (0 to 25) and bouts per year (0-80). “Many are early in their careers,” Bernick said.

The idea is similar to cohort studies such as ADNI. The fighters visit the center for a baseline measurement of family and medical history, education, and genotyping. To estimate exposure, the scientists drew up a composite index that combines data on volume, intensity, and frequency of fights. Participants come in annually for extensive cognitive testing, speech sampling, and to have blood drawn that the study banks for assaying once promising biomarker tests are available. One ELISA claiming to measure all isoforms of tau in serum was recently published (Randall et al., 2012). “This is a highly sensitive assay for tau in serum,” Max Albert Hietala of Gothenburg University in Sweden told the audience in Las Vegas.

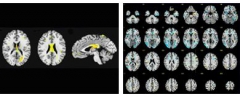

The fighters also lie down in the scanner for brain imaging with various MRI modalities including volumetrics, resting-state connectivity, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), and blood flow. By this point, 45 participants have gone through their second-year tests. In Las Vegas, Bernick summarized the first-year imaging data. On volumetric MRI, the scientists noticed that a variety of brain areas—particularly subcortical ones such as the caudate, putamen, and thalamus—tend to be smaller in fighters who had more exposure. Smaller brain volume was linked to slower processing speed on computerized cognitive testing. Atrophy appeared prior to cognitive findings. Along the same lines, resting-state functional connectivity imaging indicated disconnection in networks involving the caudate and the basal ganglia. On DTI, which images fiber tracts, the corpus callosum appeared to thin out with more exposure. Finally, cerebral blood flow was lowest in people who scored highest on impulsivity tests.

Prospective study of boxers

produces these types of brain images, among others: areas of transverse diffusivity indicating fiber tract damage (left) rise the more knockouts a boxer had, and measures of cerebral blood flow (right) decrease with increasing impulsivity. Image courtesy of Charles Bernick, Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health

These findings broadly recapitulate previous observations in the literature about brain imaging and CTE. Importantly, they come from a single, comprehensively assessed cohort in whom all measures can be compared side by side, rather than as separate bits and pieces from various different convenience samples or retrospective studies, all of which are done slightly differently. “Up to now, radiological evidence has not been terribly helpful in diagnosing CTE. We will need a multimodal approach to distinguish between chronic effects of brain injury and CTE,” said Martha Shenton of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, who runs the brain imaging component of a separate study of concussed athletes (see Part 5 of this series).

At present, this dataset is still cross sectional. Drawing exposure trajectories from it, Bernick suggested that up to five years of fighting generates few findings, but after that, decline across these measures becomes apparent. “Maybe there is a threshold of what the brain can tolerate,” Bernick said.

Once the study is complete, Bernick hopes to use its data to build a tool that regulatory bodies and boxers can use to assess risk and decide when it is time to stop fighting. As a case in point, Bernick cited International Boxing Federation Welterweight Champion Meldrick “The Kid” Taylor, who continued to fight until 2001, years after he started showing outward evidence of brain injury. It is widely believed that a brutal bout in 1990 in Las Vegas—dubbed Thunder Meets Lightning—damaged Taylor’s brain. A 2003 HBO documentary showed the previously loquacious young man struggling with slurred speech (see more on Taylor).

Does the Cerebrospinal Fluid Flag CTE?

Bernick’s study does not currently collect cerebrospinal fluid CSF samples from its participants. Keeping boxers and martial arts fighters committed to a multiyear intensive study is challenging as it is, Bernick said, though he is considering adding lumbar punctures to the protocol. Extensive previous research from longitudinal cohort studies in Sweden and the U.S. has established an increase in CSF total tau and hyperphosphorylated tau as people develop Alzheimer’s disease. Curiously, the same CSF tau assays are not useful in other tauopathies such as frontotemporal dementia, which shares some symptomatic and brain imaging features with CTE.

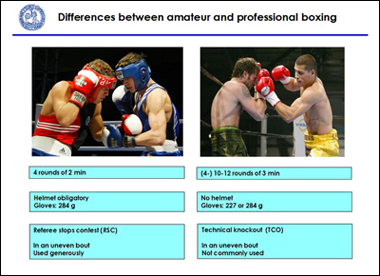

Swedish researchers have, however, detected changes in CSF proteins after traumatic brain injury in boxers soon after a bout. In Las Vegas, Hietala told the audience that when a boxer takes a punch to the head, neurons get sheared, axons are injured, and proteins leak out. This is detectable in the CSF. Working with Henrik Zetterberg and Kaj Blennow at Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg, Hietala studied 14 Swedish amateur Olympic boxers and 10 healthy controls, with the support of the boxers’ coaches. In CSF samples collected days after a bout, the neurologists detected a sharp increase in the cytoskeleton component neurofilament light protein, plus a less dramatic increase in tau. Both changes receded to normal after three months of rest (Zetterberg et al., 2006). This paper appeared the same year as another one linking CSF tau to a one-year outcome in 39 people with severe brain trauma (Ost et al., 2006). “Neurofilament light protein, in particular, is a robust marker for axonal injury after concussions,” Hietala said.

This clear finding surprised him, because Swedish amateur boxing would be considered “sissy fighting” in the U.S., Hietala said. Wearing extra padded helmets and gloves, boxers face off for only four rounds, and the referee stops the game when a boxer seems groggy.

Either way, boxing is not for "sissies." Image courtesy of Kaj Blennow, Sahlgrenska University Hospital

“This was an explosive topic in Sweden,” Hietala recalled. The medical committee of the Swedish Boxing Association subsequently initiated its own study of 30 amateur Olympic boxers and 25 controls led by Sanna Neselius, a boxer-turned-neurosurgeon. Hietala said it was widely assumed this second study was intended to disprove the initial report. Instead, it resoundingly confirmed it, and even found that in a subgroup of boxers, the CSF elevation of neurofilament light protein and tau did not recover to baseline after several weeks, possibly indicating “ongoing degeneration” (Neselius et al., 2012). Recently, the Swedish researchers have tested the tau assay reported by Randall et al. in samples of these same boxers. “Although the timing of the sampling was optimized for CSF biomarker changes, we saw higher serum tau levels in the boxers,” Zetterberg wrote to Alzforum, adding that future studies may want to take samples hours, not days, after the concussion.

Do as this doctor told you! Sanna Neselius, boxer-turned-neurosurgeon, studies CSF changes in boxers with Max Albert Hietala. Image courtesy of Sanna Neselius

No CSF study on American boxing has yet been published. In 2005, the World Medical Association recommended a ban on boxing.

Not all hits to the head are equally bad, however. In a separate study that measured the same markers in the University of Gothenburg Medical School soccer team, the Swedish neurologists found no changes in the CSF of 23 students who headed 20 corner kicks in a row, even if they got dizzy doing so (Zetterberg et al., 2007). Biomechanics researchers at the Lou Ruvo Center conference noted that when flexed neck muscles support the head in an anticipated soccer header, the uncontrolled, whip-like rotational acceleration of the head that injures axons may not happen.—Gabrielle Strobel.

This is Part 2 of a six-part series. See also Part 1, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6. Read a PDF of the entire series.

References

News Citations

- Butting Heads—Autopsies Fuel Debate on Football and Neurodegeneration

- CTE Needs Consensus on Lifetime Diagnosis

- Meet the New Progressive Tauopathy: CTE in Athletes, Soldiers

- CTE: Trauma Triggers Tauopathy Progression

- Do Tau "Prions" Lead the Way From Concussions to Progression?

- CTE Advocates Pivot Toward Preventing Concussions in Kids

Paper Citations

- Omalu BI, DeKosky ST, Hamilton RL, Minster RL, Kamboh MI, Shakir AM, Wecht CH. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in a national football league player: part II. Neurosurgery. 2006 Nov 1;59(5):1086-92; discussion 1092-3. PubMed.

- Randall J, Mörtberg E, Provuncher GK, Fournier DR, Duffy DC, Rubertsson S, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Wilson DH. Tau proteins in serum predict neurological outcome after hypoxic brain injury from cardiac arrest: Results of a pilot study. Resuscitation. 2012 Aug 9; PubMed.

- Zetterberg H, Hietala MA, Jonsson M, Andreasen N, Styrud E, Karlsson I, Edman A, Popa C, Rasulzada A, Wahlund LO, Mehta PD, Rosengren L, Blennow K, Wallin A. Neurochemical aftermath of amateur boxing. Arch Neurol. 2006 Sep;63(9):1277-80. PubMed.

- Ost M, Nylén K, Csajbok L, Ohrfelt AO, Tullberg M, Wikkelsö C, Nellgård P, Rosengren L, Blennow K, Nellgård B. Initial CSF total tau correlates with 1-year outcome in patients with traumatic brain injury. Neurology. 2006 Nov 14;67(9):1600-4. PubMed.

- Neselius S, Brisby H, Theodorsson A, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Marcusson J. CSF-biomarkers in Olympic boxing: diagnosis and effects of repetitive head trauma. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e33606. PubMed.

- Zetterberg H, Jonsson M, Rasulzada A, Popa C, Styrud E, Hietala MA, Rosengren L, Wallin A, Blennow K. No neurochemical evidence for brain injury caused by heading in soccer. Br J Sports Med. 2007 Sep;41(9):574-7. PubMed.

Other Citations

External Citations

Further Reading

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

�

Dr. Cantu's team is responsible for uncovering and reporting the accurate historical facts regarding CTE:

"CTE first showed up in a chapter titled 'Punch drunk syndrome: The chronic traumatic encephalopathy of boxers,' that the British neurologist MacDonald Critchley contributed to a 1949 book edited by the French neurosurgeon Clovis Vincent."

He reported this both at the Lou Ruvo Center and again in Zurich. He mentioned a paper soon to appear. I am glad he finally cleared up the confusion with Omalu and Miller (see blog post).

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.