Exercise Program Fails to Ease Dementia

Quick Links

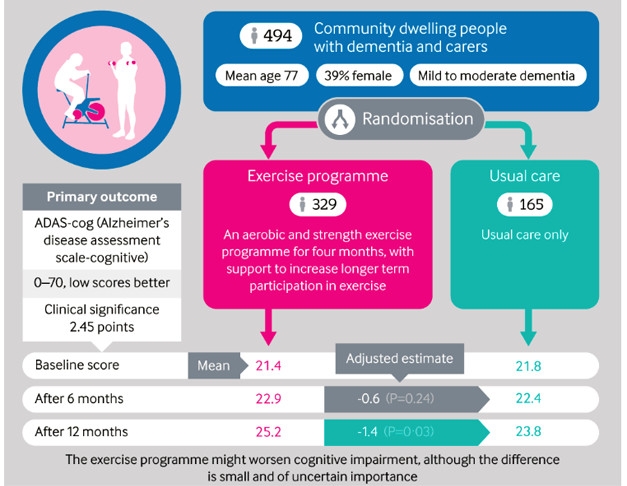

A yearlong program of brisk exercise in people with mild to moderate dementia left participants more physically fit, but no better off in terms of mental functioning, daily living, or quality of life. In fact, the intensive exercise program may have slightly worsened their cognition. The results of the randomized trial, led by Sallie Lamb of the University of Oxford, appeared May 16 in The BMJ.

- The power of exercise to slow established cognitive decline is unclear.

- Researchers enrolled 494 people with dementia to a randomized trial of moderate to intense exercise for one year.

- They became physically fitter, but their cognition worsened.

Researchers know that staying fit in midlife lowers dementia risk (Mar 2018 news), but they don’t know whether boosting fitness in later life improves cognition and function in people with established dementia. Systematic reviews of previous, mostly small and heterogeneous trials yield conflicting results (Forbes et al., 2015; Groot et al., 2016).

To test the effect of a defined regimen in a larger number of people, the Dementia and Physical Activity (DAPA) trial assigned 329 volunteers with mild to moderate dementia to an aerobic exercise and strength-training program; an additional 165 continued with standard care. Twice a week for four months, the exercisers attended supervised workouts where they spent up to 30 minutes pedaling a stationary bike and then lifted weights to strengthen their arms and legs. They did an additional hourlong session at home each week, and then kept exercising at home for one year. Most people successfully followed the program—two-thirds attended most of their scheduled sessions and 85 percent reported continuing the program at home. The goal was to boost blood flow and muscle mass, in hopes that better vascular and metabolic function would pay off in better brain health.

Fitness Test: In a randomized trial of exercise in people with dementia, scores on the ADAS-Cog after 12 months worsened compared to usual care. [Courtesy of Lamb et al., 2018.]

After 12 months of training, the exercisers were able to ride the bikes longer and lift more weights but posted no gain in mental function. They even posted a small but statistically significant increase in ADAS-Cog score, signaling more slippage. Exercise did not change other outcomes, including activities of daily living or health-related quality of life.

Eric Larson, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute in Seattle, called the trial definitive. “As a controlled trial of exercise, it’s admirable. They got good compliance in a challenging population. The results suggest that once a person has mild to moderate dementia, a vigorous exercise program doesn’t do anything but improve fitness. It’s not a magic bullet,” Larson said. He also noted the 25 adverse events, ranging from angina to falls and worsening pain. “This level of exercise does run the risk of injury in a population like this,” he told Alzforum.

Larson said in many exercise studies, most of the benefit accrues to people who are initially sedentary and then begin exercising. In this study, the investigators added exercise on top of what people were already doing, which ranged from nothing to regular running. Still, subgroup analyses taking into account starting fitness levels, type of dementia, or other variables revealed no hidden benefit for parts of the population, Lamb said.

Laura Baker of Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, wonders if the supervised part of the trial went on long enough, or if the workouts reached adequate intensity. “If we are trying to use exercise as medicine to slow disease progression, dose is important,” she said. “In my work with patients with mild cognitive impairment, it takes at least six months of moderate to high-intensity aerobic exercise, with weekly trainer support and accountability, to see improvements in executive function. To get similar improvements in people with dementia, they might need to exercise for a longer period of time,” she said. Baker also noted half the participants reported activity-limiting joint or muscle pain, which may have hampered their ability to exercise intensely enough to have an effect.

Researchers don’t know why cognition declined slightly, or whether the change is clinically significant. One possible explanation is that the added strain of exercise is detrimental to an already struggling brain. “We assumed that the beneficial effect of exercise on the healthy brain would also apply here, but I suspect that the brain that has dementia is stressed, and I wonder if it’s actually quite vulnerable,” Lamb said.

The British National Health Service commissioned the study, to determine whether providing a structured, specialized exercise program could help people with dementia. Lamb said the answer is clear. “We can say this is not a good investment for the NHS. This particular exercise program didn't help people to improve cognition or other types of outcomes the health service wants.”

That’s not to say people should abandon exercise, said Lamb. “Even if exercise does not improve cognition, if it helps people to maintain their ability to walk, or to stand up from a chair, that improves their quality of life. There’s nothing in our results to advise against starting or maintaining some kind of gentle and enjoyable activity,” Lamb said. She’d also like to test different kinds of exercise in this population.—Pat McCaffrey

References

News Citations

Paper Citations

- Forbes D, Forbes SC, Blake CM, Thiessen EJ, Forbes S. Exercise programs for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Apr 15;4:CD006489. PubMed.

- Groot C, Hooghiemstra AM, Raijmakers PG, van Berckel BN, Scheltens P, Scherder EJ, van der Flier WM, Ossenkoppele R. The effect of physical activity on cognitive function in patients with dementia: A meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Ageing Res Rev. 2016 Jan;25:13-23. Epub 2015 Nov 28 PubMed.

Further Reading

Primary Papers

- Lamb SE, Sheehan B, Atherton N, Nichols V, Collins H, Mistry D, Dosanjh S, Slowther AM, Khan I, Petrou S, Lall R, DAPA Trial Investigators. Dementia And Physical Activity (DAPA) trial of moderate to high intensity exercise training for people with dementia: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2018 May 16;361:k1675. PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

Screen, Inc.

There are several contextual factors which may influence the results of exercise studies. The studies with the most positive results are designed and performed under very unusual circumstances by extreme exercise enthusiasts, without concern for the implementation restraints upon actual clinical practice. Motivational factors may also influence the results of dietary and cognitive enrichment programs. In the present case, a British government health service wants to know the cost effectiveness and clinical significance they can expect from an exercise program implemented when patients are usually identified as appropriate (i.e., they already have dementia). Contrast that with a comprehensively funded study designed to identify subjects as early as possible, select out the most motivated, and then give "at least six months of moderate to high-intensity aerobic exercise, with weekly trainer support and accountability." That "dose" level prohibits any consideration of cost, to say nothing of the ways that data are cherry-picked by intervention enthusiasts. The academic issue (whether intensive cardiac intervention improves brain functioning) appears completely divorced from the practical questions about what is "a good investment."…More

Dr. Lamb proposes muscle toning that is gentle and enjoyable to maintain quality of life. It would be interesting to see how many of the high-intensity aerobic study subjects would settle for "maintaining their ability to stand up from a chair." As a high-intensity exerciser myself, I have asked others in that group of their plans should they be diagnosed with dementia. None of them report that they would choose to continue living, a reason why the results of cognitive testing must always be conveyed in a controlled clinical setting.

EPFL

These are very interesting findings, highlighting the importance to get a better understanding of the mechanisms by which physical activity confers its beneficial effects on brain function. In line with the mentioned suggestion that dementia brains might be too vulnerable for beneficial effects of exercise, we propose reduced specific reserve capacities of neurodegeneration-affected brains, preventing them from profiting from exercise-imposed challenges. We describe potential mechanisms in a comment to the original article here.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.