Japanese ADNI Data Parallel North American ADNI, Encouraging Global Trials

Quick Links

The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative laid the groundwork for secondary prevention trials by determining rates of progression at the early stages of disease. How well do data from this U.S. study translate to other countries? Findings from the Japanese ADNI, published today in Alzheimer’s & Dementia, suggest the disease advances similarly in this population. Researchers led by Takeshi Iwatsubo at the University of Tokyo followed 537 people with mild AD, mild cognitive impairment, or normal cognitive health, for an average of three years, using the same protocols as the U.S. ADNI. For prodromal disease, they found that the rates of cognitive decline exactly mirrored those in ADNI. Japanese participants with mild AD had better baseline cognitive scores and declined more slowly than those in the North American ADNI. It is unclear if this represents a biological difference, or merely a discrepancy in how early AD was diagnosed in each population. Amyloid positivity was similar between the two studies. “This [study] demonstrates that ADNI methodologies and findings apply to the Asian population,” Iwatsubo wrote to Alzforum.

- J-ADNI and ADNI found identical rates of cognitive decline in prodromal AD.

- Mild AD patients in J-ADNI declined more slowly than in ADNI.

- The similarities between the data sets bode well for international trials.

Researchers hailed the publication. “These [ADNI studies] are critically important for understanding what we’re seeing in trial data,” said Laurie Ryan at the National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, Maryland. Johan Luthman at Eisai Pharmaceuticals said researchers will use the J-ADNI findings to design trials in the Japanese population. “ADNI data has been fundamental for the design of disease-modification trials in the Alzheimer’s arena in the last 10 years. We’re starving for [global] data,” he told Alzforum.

The Japanese government funds a follow-up project, the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) preclinical AD study. In addition, Japanese researchers are working to facilitate research and drug development through public-private partnerships, and Iwatsubo and colleagues recently hosted an international roundtable on this topic.

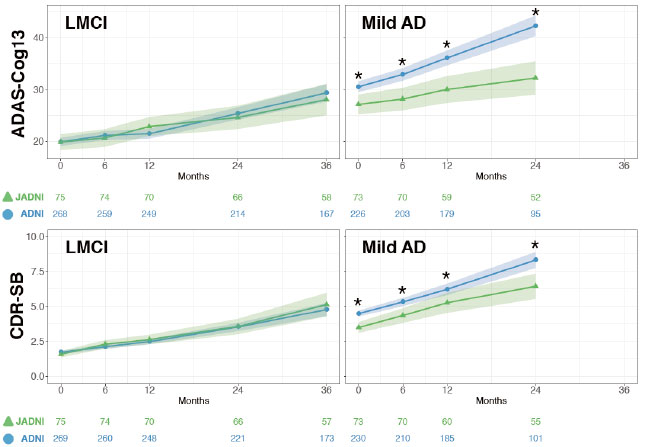

Similar Profiles. People with late MCI (left) worsened at the same rate in J-ADNI (green) and ADNI (blue), but in those with mild AD (right), the deterioration was significantly slower (asterisks) in J-ADNI. Colored numbers indicate sample sizes at each time point. [Courtesy of Iwatsubo et al., Alzheimer’s & Dementia.]

ADNI launched in 2005 and its latest iteration, ADNI3, continues today (Mar 2005 news; 2008 news series; Oct 2010 news). The initiative inspired similar studies worldwide, with the Japanese version being its closest cousin, sticking to the same protocols, recruitment criteria, and outcome measures (Oct 2008 news; Feb 2011 news).

Of the 537 people in J-ADNI, 149 had mild AD, 234 had MCI, and 154 were cognitively normal. About half the participants underwent amyloid PET scanning or lumbar punctures to assess amyloid accumulation. As in ADNI, the percentage who were positive for amyloid climbed with increasing disease stage, from 23 percent of controls to 67 percent of MCI to 88 percent of AD patients. While the latter two figures are similar to those in ADNI, amyloid positivity in controls was strikingly lower in J-ADNI compared to the 44 percent of ADNI controls testing positive. This might be due to age differences, the authors noted; with a mean age of 74, ADNI controls were six years older than those in J-ADNI. Another possibility is that more people at high risk of AD volunteered in the U.S. than in Japan. Half of U.S. controls reported a family history of the disease, as compared with 43 percent of Japanese controls.

About 24 percent of cognitively normal participants in J-ADNI carried an ApoE4 allele, nearly the same as the 28 percent in ADNI, even though there are fewer ApoE4 carriers in Asian than European populations. “I was surprised by that,” noted Eric Reiman of Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, Phoenix. It is unclear why there were so many carriers in the study, though it may suggest a selection bias that could limit how well these findings generalize to the broader population, he added.

Among the MCI groups, decline on the MMSE, ADAS-Cog13, CDR-SB, and FAQ was nearly identical in J-ADNI and ADNI (see image). However, the J-ADNI MCI group progressed to dementia more quickly, with 29 percent receiving that diagnosis after a year, and 40 percent by 18 months, compared with 20 and 27 percent in ADNI at those time points. The percent of ADNI MCI participants who developed dementia had caught up by two years. Possibly, clinicians in the Japanese study diagnosed AD at an earlier time in the disease trajectory than did those in the U.S. and Canada, the authors suggested.

Supporting this, people diagnosed as AD in J-ADNI were less impaired at baseline than in the North American ADNI, with 70 percent receiving the lowest CDR rating of 0.5, compared with 48 percent of ADNI participants, and scoring better on the ADAS-Cog and FAQ. In addition, J-ADNI AD patients declined more slowly than those in the U.S./Canada on the MMSE, ADAS-Cog13, and CDR-SB. “It is well known that participants who are less impaired at baseline will progress more slowly,” commented John Morris at Washington University, St. Louis.

An earlier diagnosis could be due to cultural differences. One factor is how well a person manages activities of daily living, and that may depend on the surrounding community, the authors suggested. Iwatsubo noted that the J-ADNI study focused on the MCI to AD transition point, perhaps leading clinicians to pay more attention to the earliest signs of dementia. Howard Feldman at the University of California, San Francisco, suggested stratifying future trial participants by a severity factor such as CDR to make recruitment more uniform (see comment below). On the other hand, underlying genetic differences could account for the discrepancy. GWAS studies will be crucial for dissecting this issue, Ryan said.

Overall, researchers said the similarities between the datasets far outweighed the differences. “I found this very encouraging, in terms of the ability to harmonize data in international studies,” Reiman said.

Data from J-ADNI is available to researchers on the Japanese National Bioscience Database Center website. For biomarker and cognitive data, researchers need to apply and explain how the data will be used. This makes access more limited than for ADNI data, Luthman noted. Because ADNI posts the raw data, researchers can analyze the data set any way they want; this is not yet possible with J-ADNI data. Iwatsubo said that J-ADNI researchers are considering linking their database to the Global Alzheimer’s Association Interactive Network (GAAIN) to improve access (Nov 2016 news).

This crucial data comes after J-ADNI was thrown into crisis in 2014 when a former J-ADNI investigator falsely accused the study of mishandling data, and media outlets misrepresented statements by other J-ADNI investigators (Jan 2014 news). The resulting furor caused the government to halt data collection a few months early and cancel the grant for a planned J-ADNI2 study, Iwatsubo said. Two investigations by the University of Tokyo and one by a third-party committee subsequently cleared J-ADNI investigators of any wrongdoing, finding no problems with data handling or quality, as J-ADNI and international investigators had insisted at the time.

To replace the cancelled J-ADNI2, the Japanese government issued a grant for the AMED preclinical study in 2015. Hiroshi Mori, of Osaka City University, leads the study. It had to start from scratch, since J-ADNI rollover participants and private funding had been lost due to the delay. Fewer than a dozen participants have enrolled so far, leaving the future of the study in doubt, Iwatsubo told Alzforum.

Nonetheless, Iwatsubo believes J-ADNI created lasting gains for Japanese Alzheimer’s research. It established the infrastructure to run AD trials of disease-modifying therapies supported by public-private partnerships, he wrote to Alzforum. He noted that Japan now has an AD industry scientific advisory board composed of 11 companies, and an imaging scientific advisory board seating seven more. A network of 38 AD clinical sites exists, as well as an amyloid imaging core with standardized protocols.

Iwatsubo is capitalizing on this infrastructure to further advance Alzheimer’s research. He convened a March 16 roundtable in Tokyo, where academic researchers, pharma representatives, and patient advocates from around the world met to brainstorm ways to address the disease by 2025. The group called for the Japanese prime minister to use his upcoming presidency of the G20 to advance Alzheimer’s research. In particular, they recommended connecting regional clinical trial networks into an international system, and establishing a global fund to fight dementia. The meeting was part of the World Dementia Council launched in 2013 (Dec 2013 conference news; Jul 2014 conference news).—Madolyn Bowman Rogers.

References

News Citations

- Sorrento: ADNI Imagines the Future of AD Imaging

- Research Brief: Announcing ADNI2—Funding for Five More Years

- Worldwide ADNIs: Other Nations Follow Suit

- Miami: Updates on J-ADNI, 18F Tracers, Biopsies

- EMIF, GAAIN: Online Gateways to Reams of Alzheimer’s Data

- Japanese ADNI Called to Defend Its Data Handling

- G8 Vows to Improve Care, Cure Dementia

- Global Endeavor Underway to Treat Dementia

Series Citations

External Citations

Further Reading

Primary Papers

- Iwatsubo T, Iwata A, Suzuki K, Ihara R, Arai H, Ishii K, Senda M, Ito K, Ikeuchi T, Kuwano R, Matsuda H, Sun CK, Beckett LA, Petersen RC, Weiner MW MW, Aisen PS PS, Donohue MC, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Japanese and North American Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative studies: Harmonization for international trials. Alzheimers Dement. 2018 May 9.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

University of California, San Diego

The results of this paper by Itwatsubo et al. comparing baseline characteristics and longitudinal clinical outcomes of late MCI and mild AD between JADNI and ADNI are important to those who are designing clinical trials that cover the spectrum of early AD. The weakness of this designated distinction between late MCI and mild AD, is that it is clinically but not biologically determined. The defining criteria that were used overlapped considerably in MMSE range (24-30 for LMCI vs 20-26 for mild AD), in CDR stages (0.5 for LMCI and mild AD and 1.0 for mild AD) and in their defined episodic memory impairment. Nevertheless, it is apparent that despite the overlap, the defined mild AD group differed significantly in ADNI versus JADNI, with JADNI enrolling a more mildly impaired population who declined more slowly on cognitive, global, and functional measures. As this applies to clinical trials and the potential for pooling of data, these results suggest that caution is in order. Care should be given in the randomization approach to early AD trials, particularly in stratifying broadly defined study populations of early AD, which includes LMCI and mild AD. Modelling with effect sizes determined from stratified subgroups and balancing recruitment by a severity stratification factor such as CDR 0.5 and CDR 1.0 could help address these findings. Additionally it would be best to investigate treatment by severity interaction in early phase trials before undertaking a large inclusive later stage trial.

Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry

The results of the JADNI project have given us a wealth of information. In particular, the very similar progress of MCI in Japan and the United States shows that Alzheimer’s disease might be fundamentally different from conventional diseases.

In the past, there were far fewer Alzheimer patients. Therefore, Alzheimer’s may be described as a phenomenon created by increased longevity, apart from some rare exceptions such as juvenile Alzheimer’s. If Alzheimer’s is caused by aging, it is important that we diagnose the symptoms early and respond appropriately. Furthermore, unlike conventional diseases, Alzheimer’s may be caused by various factors being mutually related at the same time.

An important contribution to the study of AD, the JADNI project made it possible to effectively gather research data worldwide by providing a standard for data quality. For future research, accurately grasping the symptoms related to this multifactorial disease and performing multiple analyses will be indispensable. From this point of view, future Japanese research is expected to greatly contribute to the world in terms of collecting high-quality data on multiple factors and performing multi-analysis using artificial intelligence.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.