Evidence Mounts That Mitochondrial Gene Is Bona Fide ALS, FTD Risk Factor

Quick Links

Just three months after a paper outed a gene for a mitochondrial protein as a potential cause of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-frontotemporal dementia, four new publications have made the case clear. CHCHD10 is an ALS/FTD spectrum gene. A handful of different mutations in the gene whose acronym stands for the tongue twister coiled-coil-helix-coiled-coil-helix domain containing 10 cause a range of symptoms comprising ALS-FTD, ALS, and also mitochondrial myopathy, according to the studies. “It became clear in recent weeks that this is a ‘true’ ALS gene,” wrote Jochen Weishaupt of Ulm University in Germany, author on one of the new papers, in an email to Alzforum (Müller et al., 2014).

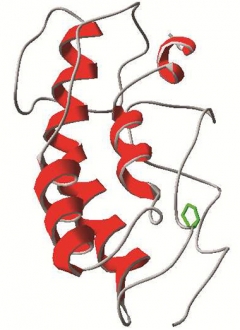

Researchers based this model for CHCHD10 on the structure of the related CHCHD5. In some cases of ALS, proline 34 (green) is mutated to serine. [Image courtesy of Chaussenot et al.]

Last June, Véronique Paquis-Flucklinger and colleagues from the Université de Nice Sophia Antipolis in France described a French family with a type of myopathy plus atypical ALS-FTD features due to a serine-59-leucine CHCHD10 mutation, and a single Spaniard with ALS-FTD due to the same amino acid swap (see Jun 2014 news story. In July, the same authors followed up with publication of two more cases, proline-34-serine mutations this time, from a French cohort with FTD-ALS (Chaussenot et al., 2014.

In August, Weishaupt and colleagues added two Germans with ALS due to arginine-15-leucine mutations and a Finn with ALS caused by a glycine-66-valine substitution. Then in September, scientists led by Teepu Siddique of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago reported CHCHD10 mutations in a Puerto Rican family. In this kindred, which exhibited mitochondrial myopathy, members carry two substitutions in the gene, arginine-155-serine and glycine-58-arginine (Ajroud-Driss et al., 2014). Siddique originally reported the CHCHD10 finding at the 2012 American Academy of Neurology meeting in New Orleans (Ajroud-Driss et al., 2012).

In the latest paper, a letter in the September 26 Brain online, researchers from the National Institute on Aging in Bethesda, Maryland, describe one family and two unrelated ALS cases due to an R15L substitution in CHCHD10. This finding results from the first whole-genome sequencing of familial ALS cases by a consortium led by senior author Bryan Traynor of the NIA. All told, that makes 11 published families or cases with CHCHD10 mutations. Experts who spoke with Alzforum estimated that mutations in this gene might account for 2–5 percent of ALS and ALS-FTD cases.

The French kindred published in June had a primarily muscle disease with some features reminiscent of ALS and FTD, leading ALS clinicians to question how appropriate it was at that time to label CHCHD10 an ALS gene. Including the new cases, the phenotypes span pure ALS to ALS-FTD to myopathy. Bulbar symptoms—problems with speaking or eating—are common in the cases reported so far. Several of the newly reported cases “do sound more like ALS than the cases in the original paper did,” commented Richard Bedlack of the Duke ALS Clinic in Durham, North Carolina (see full comment below). “The ALS is atypical because of the slow progression, but that is within the range of what we see in our clinics.” People with CHCHD10 mutations have survived for up to 17 years past the onset of symptoms in Paquis-Flucklinger’s original report, compared to two to three years for typical ALS.

In the September Brain paper, first author Janel Johnson of the NIA and colleagues initially tried whole-exome sequencing to identify the disease-causing mutation in four people from a large family with ALS. Though the CHCHD10 substitution occurs in an exon, technical trouble kept it from coming to light, said co-author Ekaterina Rogaeva from the University of Toronto. Sometimes, certain areas of the exome are incompletely sequenced, for example when DNA primers bind poorly. Johnson and colleagues had to use whole-genome sequencing to find the CHCHD10 mutation. The high proportion of guanine and cytosine in the CHCHD10 gene could have interfered with the exome sequencing, agreed Paquis-Flucklinger and colleagues in a response to Johnson’s work (Bannwarth et al., 2014). The strong bonds between those nucleotides can interfere with sequencing and primer binding due to their high melting temperature. “The coverage and reliability of whole-genome sequencing is better than whole exome,” Rogaeva said, suggesting other genetic sleuths should take note.

CHCHD10 provides the strongest evidence yet that mitochondria contribute to motor neuron disease, Rogaeva noted. Little is known about the protein’s function; it is thought to contribute to oxidative phosphorylation (Martherus et al., 2010). Paquis-Flucklinger and colleagues reported that their myopathy patients had disorganized mitochondria with fragmented DNA. The scientists have suggested the mutation could interfere with protein stability or protein-protein interactions.

In ALS cases, the pathology appears different, Siddique told Alzforum. In work not yet reported, his group analyzed spinal cord tissue from people with CHCHD10 mutations who died of ALS. The Chicago scientists saw skein-shaped cytoplasmic inclusions and denervation characteristic of the disease. “Mitochondria may contribute to the disease, but the problem is proteins that aggregate elsewhere,” Siddique said.

Traynor continues to collect cases for sequencing, and Rogaeva predicts other ALS genes will be found in the next several years.—Amber Dance

References

News Citations

Paper Citations

- Müller K, Andersen PM, Hübers A, Marroquin N, Volk AE, Danzer KM, Meitinger T, Ludolph AC, Strom TM, Weishaupt JH. Two novel mutations in conserved codons indicate that CHCHD10 is a gene associated with motor neuron disease. Brain. 2014 Dec;137(Pt 12):e309. Epub 2014 Aug 11 PubMed.

- Chaussenot A, Le Ber I, Ait-El-Mkadem S, Camuzat A, de Septenville A, Bannwarth S, Genin EC, Serre V, Augé G, French research network on FTD and FTD-ALS, Brice A, Pouget J, Paquis-Flucklinger V. Screening of CHCHD10 in a French cohort confirms the involvement of this gene in frontotemporal dementia with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Neurobiol Aging. 2014 Dec;35(12):2884.e1-4. Epub 2014 Jul 24 PubMed.

- Ajroud-Driss S, Fecto F, Ajroud K, Lalani I, Calvo SE, Mootha VK, Deng HX, Siddique N, Tahmoush AJ, Heiman-Patterson TD, Siddique T. Mutation in the novel nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein CHCHD10 in a family with autosomal dominant mitochondrial myopathy. Neurogenetics. 2014 Sep 6; PubMed.

- Ajroud-Driss S, Fecto F, Ajroud K, Siddique T. Mutations in the Nuclear Encoded Novel Mitochondrial Protein CHCHD10 Cause an Autosomal Dominant Mitochondrial Myopathy. Neurology. 2012 Apr 26;78(Suppl 1): S55.001.

- Bannwarth S, Ait-El-Mkadem S, Chaussenot A, Genin EC, Lacas-Gervais S, Fragaki K, Berg-Alonso L, Kageyama Y, Serre V, Moore D, Verschueren A, Rouzier C, Le Ber I, Augé G, Cochaud C, Lespinasse F, N'Guyen K, de Septenville A, Brice A, Yu-Wai-Man P, Sesaki H, Pouget J, Paquis-Flucklinger V. Reply: Mutations in the CHCHD10 gene are a common cause of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2014 Sep 26; PubMed.

- Martherus RS, Sluiter W, Timmer ED, VanHerle SJ, Smeets HJ, Ayoubi TA. Functional annotation of heart enriched mitochondrial genes GBAS and CHCHD10 through guilt by association. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010 Nov 12;402(2):203-8. Epub 2010 Oct 1 PubMed.

External Citations

Further Reading

Papers

- Bannwarth S, Ait-El-Mkadem S, Chaussenot A, Genin EC, Lacas-Gervais S, Fragaki K, Berg-Alonso L, Kageyama Y, Serre V, Moore D, Verschueren A, Rouzier C, Le Ber I, Augé G, Cochaud C, Lespinasse F, N'Guyen K, de Septenville A, Brice A, Yu-Wai-Man P, Sesaki H, Pouget J, Paquis-Flucklinger V. Reply: Two novel mutations in conserved codons indicate that CHCHD10 is a gene associated with motor neuron disease. Brain. 2014 Aug 11; PubMed.

- Stribl C, Samara A, Trümbach D, Peis R, Neumann M, Fuchs H, Gailus-Durner V, Hrabě de Angelis M, Rathkolb B, Wolf E, Beckers J, Horsch M, Neff F, Kremmer E, Koob S, Reichert AS, Hans W, Rozman J, Klingenspor M, Aichler M, Walch AK, Becker L, Klopstock T, Glasl L, Hölter SM, Wurst W, Floss T. Mitochondrial dysfunction and decrease in body weight of a transgenic knock-in mouse model for TDP-43. J Biol Chem. 2014 Apr 11;289(15):10769-84. Epub 2014 Feb 10 PubMed.

- Stoica R, De Vos KJ, Paillusson S, Mueller S, Sancho RM, Lau KF, Vizcay-Barrena G, Lin WL, Xu YF, Lewis J, Dickson DW, Petrucelli L, Mitchell JC, Shaw CE, Miller CC. ER-mitochondria associations are regulated by the VAPB-PTPIP51 interaction and are disrupted by ALS/FTD-associated TDP-43. Nat Commun. 2014 Jun 3;5:3996. PubMed.

Primary Papers

- Johnson JO, Glynn SM, Gibbs JR, Nalls MA, Sabatelli M, Restagno G, Drory VE, Chiò A, Rogaeva E, Traynor BJ. Mutations in the CHCHD10 gene are a common cause of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2014 Dec;137(Pt 12):e311. Epub 2014 Sep 26 PubMed.

- Chaussenot A, Le Ber I, Ait-El-Mkadem S, Camuzat A, de Septenville A, Bannwarth S, Genin EC, Serre V, Augé G, French research network on FTD and FTD-ALS, Brice A, Pouget J, Paquis-Flucklinger V. Screening of CHCHD10 in a French cohort confirms the involvement of this gene in frontotemporal dementia with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Neurobiol Aging. 2014 Dec;35(12):2884.e1-4. Epub 2014 Jul 24 PubMed.

- Müller K, Andersen PM, Hübers A, Marroquin N, Volk AE, Danzer KM, Meitinger T, Ludolph AC, Strom TM, Weishaupt JH. Two novel mutations in conserved codons indicate that CHCHD10 is a gene associated with motor neuron disease. Brain. 2014 Dec;137(Pt 12):e309. Epub 2014 Aug 11 PubMed.

- Ajroud-Driss S, Fecto F, Ajroud K, Lalani I, Calvo SE, Mootha VK, Deng HX, Siddique N, Tahmoush AJ, Heiman-Patterson TD, Siddique T. Mutation in the novel nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein CHCHD10 in a family with autosomal dominant mitochondrial myopathy. Neurogenetics. 2014 Sep 6; PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

NIH/NINDS

I consider the latest results from Johnson and colleagues, along with the earlier reports of the French and German teams (Bannwarth et al., 2014; Chaussenot et al., 2014; Muller et al., 2014), as pretty compelling evidence for CHCHD10’s role as a disease gene of familial ALS and ALS-FTD. Analysis of the CHCHD10 gene in additional, well-phenotyped familial ALS and ALS-FTD cases should provide further insight into the relative frequency of disease-causing CHCHD10 mutations in this spectrum of neurodegenerative disorders.

The affected members of the initial family that led to the discovery of disease-causing CHCHD10 mutations had a complex clinical picture that seemed to go beyond an ALS-FTD phenotype. However, the more recent studies by the U.S. and German teams identified CHCHD10 mutations in cases with a confirmed ALS diagnosis, suggesting that CHCHD10 should indeed be added to the growing list of ALS disease genes. Deep phenotyping of additional patients with CHCHD10-linked disease is warranted to provide a better understanding of the clinical presentation of this genetic subgroup.…More

Previous research has implicated mitochondrial dysfunction in ALS mostly through the analysis of model systems of mutant SOD1-linked ALS and, more recently, mutant VCP-linked ALS. The discovery of ALS-causing CHCHD10 mutations provides an exciting new entry point for exploring mitochondrial dysfunction in ALS.

I expect other ALS genes to turn up. Next-generation sequencing efforts in familial ALS have mostly focused on whole-exome sequencing, which remains an incredibly powerful and efficient tool for identifying disease-causing mutations. It has already led to the discovery of a number of new ALS genes. Some groups have begun moving toward whole-genome sequencing. For sporadic ALS, whole-genome sequencing is underway by Project MinE, an initiative launched in 2013 and enabled by crowd-funding. The initiative aims to sequence at least 15,000 whole genomes of ALS patients and has already reached over 10 percent of this goal. One significant advantage of whole-genome sequencing is that it captures non-protein-coding and other intergenic regions of the genome that are missed by whole-exome sequencing. These intergenic regions may contain critical regulatory sequences that are relevant for disease. Whole-genome sequencing also has an increased capacity for covering GC-rich stretches of protein-coding sequences. As the cost of whole-genome sequencing continues to fall, it will likely gain increasing traction.

References:

Bannwarth S, Ait-El-Mkadem S, Chaussenot A, Genin EC, Lacas-Gervais S, Fragaki K, Berg-Alonso L, Kageyama Y, Serre V, Moore D, Verschueren A, Rouzier C, Le Ber I, Augé G, Cochaud C, Lespinasse F, N'Guyen K, de Septenville A, Brice A, Yu-Wai-Man P, Sesaki H, Pouget J, Paquis-Flucklinger V. Reply: Mutations in the CHCHD10 gene are a common cause of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2014 Sep 26; PubMed.

Chaussenot A, Le Ber I, Ait-El-Mkadem S, Camuzat A, de Septenville A, Bannwarth S, Genin EC, Serre V, Augé G, French research network on FTD and FTD-ALS, Brice A, Pouget J, Paquis-Flucklinger V. Screening of CHCHD10 in a French cohort confirms the involvement of this gene in frontotemporal dementia with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Neurobiol Aging. 2014 Dec;35(12):2884.e1-4. Epub 2014 Jul 24 PubMed.

Müller K, Andersen PM, Hübers A, Marroquin N, Volk AE, Danzer KM, Meitinger T, Ludolph AC, Strom TM, Weishaupt JH. Two novel mutations in conserved codons indicate that CHCHD10 is a gene associated with motor neuron disease. Brain. 2014 Dec;137(Pt 12):e309. Epub 2014 Aug 11 PubMed.

Duke University

Replication by these two other groups (Mueller et al. 2014; Johnson et al. 2014) definitely strengthens the original claim that CHCHD10 is an ALS gene (Bannwarth et al., 2014). Also, while there is still less optimal phenotypic description of the cases in these two new papers, they do appear more like ALS than did the cases in the original paper. The ALS is still atypical because of the reported slow progression rate, but it is within the range of what we see in our clinics.

References:

Müller K, Andersen PM, Hübers A, Marroquin N, Volk AE, Danzer KM, Meitinger T, Ludolph AC, Strom TM, Weishaupt JH. Two novel mutations in conserved codons indicate that CHCHD10 is a gene associated with motor neuron disease. Brain. 2014 Dec;137(Pt 12):e309. Epub 2014 Aug 11 PubMed. …More

Johnson JO, Glynn SM, Gibbs JR, Nalls MA, Sabatelli M, Restagno G, Drory VE, Chiò A, Rogaeva E, Traynor BJ. Mutations in the CHCHD10 gene are a common cause of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2014 Dec;137(Pt 12):e311. Epub 2014 Sep 26 PubMed.

Bannwarth S, Ait-El-Mkadem S, Chaussenot A, Genin EC, Lacas-Gervais S, Fragaki K, Berg-Alonso L, Kageyama Y, Serre V, Moore DG, Verschueren A, Rouzier C, Le Ber I, Augé G, Cochaud C, Lespinasse F, N'Guyen K, de Septenville A, Brice A, Yu-Wai-Man P, Sesaki H, Pouget J, Paquis-Flucklinger V. A mitochondrial origin for frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis through CHCHD10 involvement. Brain. 2014 Aug;137(Pt 8):2329-45. Epub 2014 Jun 16 PubMed.

To date, both the association of CHCHD10 with FTD-ALS and the identification of recurrent variants in ALS families from different geographical origins are solid observations that substantiate a causal genetic link between CHCHD10 mutations and the development of ALS, at least in a subset of patients. Elucidating the cellular pathways disrupted by the expression of CHCHD10 mutant alleles will be crucial in clarifying the role of mitochondrial dysfunction, not only in ALS, but also more broadly in other more complex neurodegenerative disorders.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.