Is Dementia Incidence Still Dropping? Birth Cohort Data Say Yes.

Quick Links

As the baby boom generation reaches its hopefully golden years, scientists have been projecting a doubling of dementia cases in the U.S. by 2050, alarming health care agencies, the public, and health economists. Now, a new editorial argues this “tsunami” could be more of a gentle wave. In the March 12 JAMA, Eric Stallard, Svetlana Ukraintseva, and Murali Doraiswamy at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, explain that tsunami predictions assume that dementia prevalence in each age range remains constant over time. That is not the case, they say.

- Over the last 40 years, age-adjusted dementia prevalence in the U.S. has dropped by two-thirds.

- This predicts a 25 percent rise in total dementia cases by 2050, due to population aging.

- The findings belie predictions of dementia doubling by 2050.

Their analysis of three large population studies found that age-adjusted prevalence has dropped by a whopping two-thirds over the last 40 years. In other words, every successive birth cohort has a lower risk of dementia than did its predecessor. Extrapolated forward, these rates would predict only a 25 percent bump in dementia cases by 2050. This would challenge conventional wisdom. “I feel a bit like Copernicus,” Stallard quipped.

Other scientists agreed this analysis is reasonable, and said it highlights the potential for people and societies to modify dementia risk through health and lifestyle interventions. “The authors convey a message of hope,” said Jennifer Weuve at Boston University School of Public Health. At the same time, commenters cautioned that encouraging trends toward better overall health may be erased by rising chronic health problems, such as obesity and diabetes. “Even though a dementia decline has begun, it might not last in the coming decades. The future depends on the balance of diverging trends,” Walter Rocca at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, wrote to Alzforum (comments below).

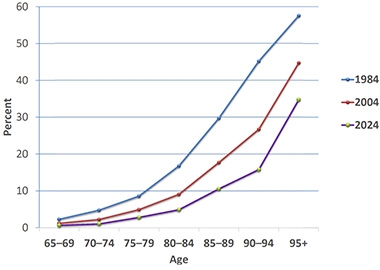

Lower Every Generation? Over the last 40 years, the percentage of people at a given age who have dementia has dropped by two-thirds, hinting that incidence has gone down over time. [Courtesy of Eric Stallard.]

Rethinking Estimates

The doubling prediction comes from applying the current dementia prevalence at each age range to the 2050 population, when the U.S. Census Bureau predicts there will be twice as many people over age 80 as there are now (Hebert et al., 2001; Rajan et al., 2021). However, several population studies have found that incidence is falling in the U.S. and Europe, raising questions about future prevalence (May 2013 news; Jul 2014 conference news; Feb 2016 news).

Stallard became aware of these declining dementia rates while leading the National Long Term Care Survey from 1984 to 2004. This study, funded by the National Institute on Aging, used Medicare data to determine how many people over age 65 had disabilities requiring long-term care. Analyzing these data for the insurance industry, Stallard found that the prevalence of severe cognitive impairment fell by 2.7 percent per year during this period (Stallard and Yashin, 2016).

To find out if the trend continued past 2004, Stallard analyzed 2000 to 2012 data from the U.S. Health and Retirement Study. Again, dementia prevalence declined about 2.5 percent per year (Nov 2016 news). Finally, data from nearly 50,000 people in the National Health and Aging Trends Study recorded a drop of 3.7 percent per year between 2011 and 2021 (Freedman and Cornman, 2024). For the 2020-2021 period, however, Stallard believes the fall was accelerated by COVID deaths among nursing home residents. For this reason, he used data from the pre-COVID years of 2011-2019, during which dementia prevalence went down 3 percent per year.

Stallard combined these three sources to estimate change over the last 40 years, using 2.7 percent as the annual decline and extrapolating that this rate would remain constant between 2019 and 2024. The analysis revealed a staggering 67 percent drop over this time period in the percentage of people who had dementia at any given age. For example, in 1984, 30 percent of people between the ages of 85 and 89 had dementia; in 2024, it was 10 percent (image above). Looking at the data another way, Stallard calculated that each successive five-year birth cohort had less dementia at a given age than did their predecessors (image below).

Dementia by Birth Year. People born in 1945 had much less dementia at a given age range than did those born in 1895. [Courtesy of Eric Stallard.]

What might this mean for the future? Carrying forward the observed declines for these current birth cohorts, dementia prevalence would rise a quarter by 2050, as the number of older people doubles. A previous analysis from scientists in the Netherlands supports this prediction, projecting 30 percent more dementia cases in 2050 than in 2020 based on data from the Rotterdam Study (Brück et al., 2022). If the risk of dementia continues to drop at the same rate in future birth cohorts, the picture would be even rosier, with only a 10 percent bump in cases by 2050, Stallard said. He is uploading his data to the NIA Linkage website so that others can analyze it.

But Will the Trend Continue?

The big questions now are what brought dementia rates down, and whether this trajectory will be maintained, Stallard noted. There have been big improvements in public health since 1895, when the oldest birth cohort he analyzed was born. Nutrition and education have gotten better, infectious disease claims fewer lives thanks to vaccines and antibiotics, and doctors manage chronic health conditions such as cardiovascular disease and stroke more effectively. Deaths from heart disease plummeted about three-quarters during the same time period in which dementia fell by two-thirds, hinting the two could be linked. A recent analysis even suggests older people can continue to improve their literacy and math skills well into their 60s (Hanushek et al., 2025).

Scientists don’t know what may have had the biggest impact, but recent studies have emphasized the effects of modifiable factors such as exercise, smoking, hearing loss, and hypertension on dementia risk (Feb 2016 news; Jul 2022 news).

“This analysis provides evidence to support our forecast from 2011, and subsequent Lancet Commission reports, which estimated that up to half of the anticipated increase in dementia due to the aging of the population could potentially be prevented through risk reduction interventions,” Deborah Barnes at the University of California, San Francisco, wrote to Alzforum (comment below). The Lancet reports highlighted education and good management of chronic diseases in delaying cognitive decline (Barnes and Yaffe, 2011; Aug 2017 news; Aug 2020 news).

At the same time, negative health trends, such as the rise in obesity and diabetes, may counteract the drop in cases. “There are major uncertainties. Risk and protective factors are changing substantially across time, and affect individuals at different life stages,” Sebastian Walsh and Carol Brayne and at the University of Cambridge wrote to Alzforum (comment below).

Will the findings apply to underrepresented groups such as blacks and Latinos? Weuve noted that they make up a growing proportion of the elderly population in the U.S., but less data are available on how dementia may be changing among them. Brayne and Walsh agreed. “There is little active fieldwork that is truly representative of the many communities within the U.S.,” they noted.

Finally, the situation may vary by country. Many studies have shown similar trends in Europe (Wolters et al., 2020; Mukadam et al., 2024), but the picture looks different in developing countries. Dementia seems to be on the rise in Latin America, India, and China (May 2012 news; Jun 2013 news). Alzheimer’s Disease International and the Global Burden of Disease Study both project a tripling of dementia worldwide by 2050 (Aug 2015 news; GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators, 2022).—Madolyn Bowman Rogers

References

News Citations

- Dementia Incidence Said to Drop as Public Health Improves

- Falling Dementia Rates in U.S., Europe Hint at Prevention Benefit

- Falling Dementia Rates in U.S. and Europe Sharpen Focus on Lifestyle

- U.S. Dementia Rates Fall

- In the U.S., 40 Percent of All-Cause Dementia Is Preventable

- Lancet Commission Claims a Third of Dementia Cases Are Preventable

- Lancet Commission’s Dementia Hit List Adds Alcohol, Pollution, TBI

- Dementia Numbers in Developing World Point to Global Epidemic

- Prevalence of Dementia, AD, in China Eclipses Predictions

- World Alzheimer Report 2015: Revised Estimates Hint at Larger Epidemic

Paper Citations

- Hebert LE, Beckett LA, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Annual incidence of Alzheimer disease in the United States projected to the years 2000 through 2050. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001 Oct-Dec;15(4):169-73. PubMed.

- Rajan KB, Weuve J, Barnes LL, McAninch EA, Wilson RS, Evans DA. Population estimate of people with clinical Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment in the United States (2020-2060). Alzheimers Dement. 2021 May 27; PubMed.

- Freedman VA, Cornman JC. Dementia Prevalence, Incidence, and Mortality Trends Among U.S. Adults Ages 72 and Older, 2011-2021. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2024 Nov 7;79(Supplement_1):S22-S31. PubMed.

- Brück CC, Wolters FJ, Ikram MA, de Kok IM. Projected prevalence and incidence of dementia accounting for secular trends and birth cohort effects: a population-based microsimulation study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2022 Aug;37(8):807-814. Epub 2022 Jun 22 PubMed.

- Hanushek EA, Kinne L, Witthöft F, Woessmann L. Age and cognitive skills: Use it or lose it. Sci Adv. 2025 Mar 7;11(10):eads1560. Epub 2025 Mar 5 PubMed.

- Barnes DE, Yaffe K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer's disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol. 2011 Sep;10(9):819-28. PubMed.

- Wolters FJ, Chibnik LB, Waziry R, Anderson R, Berr C, Beiser A, Bis JC, Blacker D, Bos D, Brayne C, Dartigues JF, Darweesh SK, Davis-Plourde KL, de Wolf F, Debette S, Dufouil C, Fornage M, Goudsmit J, Grasset L, Gudnason V, Hadjichrysanthou C, Helmer C, Ikram MA, Ikram MK, Joas E, Kern S, Kuller LH, Launer L, Lopez OL, Matthews FE, McRae-McKee K, Meirelles O, Mosley TH Jr, Pase MP, Psaty BM, Satizabal CL, Seshadri S, Skoog I, Stephan BC, Wetterberg H, Wong MM, Zettergren A, Hofman A. Twenty-seven-year time trends in dementia incidence in Europe and the United States: The Alzheimer Cohorts Consortium. Neurology. 2020 Aug 4;95(5):e519-e531. Epub 2020 Jul 1 PubMed.

- Mukadam N, Wolters FJ, Walsh S, Wallace L, Brayne C, Matthews FE, Sacuiu S, Skoog I, Seshadri S, Beiser A, Ghosh S, Livingston G. Changes in prevalence and incidence of dementia and risk factors for dementia: an analysis from cohort studies. Lancet Public Health. 2024 Jul;9(7):e443-e460. PubMed.

- GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2022 Feb;7(2):e105-e125. Epub 2022 Jan 6 PubMed.

External Citations

Further Reading

News

- Alzheimer’s Incidence is Rising, Not Falling, a Researcher Says

- Can Preserving Vision and Hearing Prevent Dementia?

- Diabetes in Mid-Life Drives Up Dementia Risk

- You Are What You Breathe: Polluted Air Tied to Plaques, Brain Atrophy

- Air Pollution and Dementia—Through Hazy Data, Links Emerge

- Blood Pressure: How Low to Prevent Dementia—and When?

- Dementia: Frailty Hastens It, Physical Activity Wards It Off

- 44-Year Study Ties Midlife Fitness to Lower Dementia Risk

- Is Alcohol Abuse a Bigger Dementia Risk Than We Thought?

- In the United States, Racial Disparities in Dementia Risk Persist

- WHO Weighs in With Guidelines for Preventing Dementia

Primary Papers

- Stallard PJ, Ukraintseva SV, Doraiswamy PM. Changing Story of the Dementia Epidemic. JAMA. 2025 Mar 12; Epub 2025 Mar 12 PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

Boston University

The report by Stallard et al. is provocative for two reasons. First, in their attempts to correct national projections of dementia prevalence for the modest downturns in prevalence reported by several studies, the authors convey a message of hope. That is to say, the future certainly holds a large percentage of older adults in the U.S. living with dementia, but that percentage and the corresponding number of their families and affected communities may be smaller than previously forecast. Prior projections typically assumed that dementia incidence and survival would remain unchanged over time.

The second reason this paper is provocative—and here I could be mistaken, but I am concerned—is that it mainly reflects the experience of white older adults. If that is the case, the hope offered—to families and to individuals—may be less. Why does this matter? The racial and ethnic composition of the U.S. older adult population is poised to change over coming decades. Among adults age 65 and older, the percentage who are black is projected to increase from 11 to 14, and the percentage who are Hispanic is slated to nearly double from 11 to 20. During this same period, the percentage who are white is projected to drop from 75 to 65. These patterns are exaggerated among those 85 and older (Census.gov). It is individuals from this group who make up most of the participants in studies of secular trends in dementia incidence and prevalence. This limitation of the evidence base was also described by the authors of the systematic review cited by the authors (Mukadam et al., 2024).

The underrepresentation of black, Hispanic/Latino older adults in research on secular trends in dementia, as in research on dementia in general, is critical because, in the U.S., black older adults have about twice the risk of dementia as do whites (Muir et al., 2024). Estimates of dementia risk in Hispanic older adults are sparser and often based on smaller sizes. Most of the few studies in this population suggest that they face dementia risks similar to that of, or exceed, the dementia risk among non-Hispanic whites (Alzheimer’s Association 2024). The few studies to evaluate how dementia prevalence and/or incidence has been changing over time among black or Hispanic older adults are equivocal. Some have found little change over time, whereas others have observed a decline in dementia prevalence among black adults, but with little change in the dementia prevalence disparity between black and white adults (Rajan et al., 2019; Chen and Zissimopoulo, 2018; Power et al., 2021).

It may be that dementia prevalence has been falling among these underrepresented populations. The evidence isn’t as robust as it is in the larger evidence among white individuals, and the evidence that does exist is based on sample sizes of black and/or Hispanic older adults that are sometimes an order of magnitude smaller than the samples of white participants. Frustrating matters further, as Livingston et al. state in their Lancet Commission report on dementia risk factors, most of what we know about how to prevent and treat dementia comes from studies of older white adults (Livingston et al., 2024). The populations of black and Hispanic older adults are growing, but we have painfully few indications about what their future dementia experience will be.

References:

Mukadam N, Wolters FJ, Walsh S, Wallace L, Brayne C, Matthews FE, Sacuiu S, Skoog I, Seshadri S, Beiser A, Ghosh S, Livingston G. Changes in prevalence and incidence of dementia and risk factors for dementia: an analysis from cohort studies. Lancet Public Health. 2024 Jul;9(7):e443-e460. PubMed.

Muir RT, Hill MD, Black SE, Smith EE. Minimal clinically important difference in Alzheimer's disease: Rapid review. Alzheimers Dement. 2024 May;20(5):3352-3363. Epub 2024 Apr 1 PubMed.

2024 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2024 May;20(5):3708-3821. Epub 2024 Apr 30 PubMed.

Rajan KB, Weuve J, Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Evans DA. Prevalence and incidence of clinically diagnosed Alzheimer's disease dementia from 1994 to 2012 in a population study. Alzheimers Dement. 2019 Jan;15(1):1-7. Epub 2018 Sep 7 PubMed.

Chen C, Zissimopoulos JM. Racial and ethnic differences in trends in dementia prevalence and risk factors in the United States. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2018;4:510-520. Epub 2018 Oct 5 PubMed.

Livingston G, Huntley J, Liu KY, Costafreda SG, Selbæk G, Alladi S, Ames D, Banerjee S, Burns A, Brayne C, Fox NC, Ferri CP, Gitlin LN, Howard R, Kales HC, Kivimäki M, Larson EB, Nakasujja N, Rockwood K, Samus Q, Shirai K, Singh-Manoux A, Schneider LS, Walsh S, Yao Y, Sommerlad A, Mukadam N. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. Lancet. 2024 Aug 10;404(10452):572-628. Epub 2024 Jul 31 PubMed.

Mayo Clinic

The projections presented by Stallard et al. are based on existing data for the United States over the past 40 years and on some important assumptions. The projections are reasonable if we accept those assumptions. On the optimistic side, we can argue that history offers reasons for hope. The burden of disease is malleable and may change with time. Humans can modify the burden of disease with political, social, and medical interventions. On the less optimistic side, we must remember that the changes in risk over time may vary by sex and gender, across ethnic and cultural groups, and across U.S. states or countries worldwide. Trends in chronic diseases, such as dementia, reflect complex interactions of multiple risk and protective factors or events. The changes are very delicate, unstable, and contingent. The incidence of dementia has declined over the past 30 or 40 years in some countries but the future remains uncertain.

We need to continue to study the trends in risk of dementia in the coming years, and we need to continue to implement interventions targeting the known modifiable risk factors. Even though a dementia decline has begun, it might not last in the coming decades. The future depends on the balance of diverging trends. The increasing education levels, the reduction in smoking and the introduction of medications to better control hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, or depression may support the prediction of a continuing reduction in risk. However, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, depression, multi-morbidity, and polypharmacy are increasing over time. These trends may dampen the decline and may even contribute to an increasing risk of dementia in the future. For example, increasing rates of dementia over time have been reported for Japan and Italy, and stable rates were reported for Nigeria.

Cambridge University

University of Cambridge

Stallard et al. have summarized existing evidence from population representative studies in the U.S. and beyond to propose that future dementia numbers may not rise as much as has been suggested by others (Stallard et al., 2025). They rightly highlight consistent findings that age-specific prevalence and incidence has been shown to be lower in more recent birth cohorts than earlier ones. They extrapolate these reductions across time to provide future scenarios that still include substantial increases in numbers due to population aging, but are less alarming.

The exercise is appropriately cautious, pointing out that there are major uncertainties. Risk and protective factors, such as obesity, diabetes, heart disease, etc., are changing substantially across time, and affect individuals at different life stages. We do not know what the causal windows might be in terms of these risk factors, and the reasons for the age-specific declines remain largely unknown. All the risk factors that we understand, including those within and outside the Lancet Commission’s most recent list (Livingston et al., 2024), cluster with disadvantage.

There is little active fieldwork that is truly representative of the many communities within the U.S., drilling down deeply to understand variation in prevalence and incidence. The large national studies are important, but they need to be supplemented by estimates from robust descriptive epidemiological work in contemporary older populations who were not included. The danger of using national studies without such additional work is that they can, despite huge efforts, still miss substantial populations at varying risk because their sampling approaches simply cannot reach those people.

Ideally, national studies would also be validated at regular intervals along the lines of the Aging Demographics and Memory Study, using both past diagnostic study criteria and those in use today (Langa et al., 2005). As with hypertension and diabetes, changing the criteria across time creates an instability in understanding what the true changes in populations are, as noted by the authors. Moving toward preclinical states automatically increases the proportion of the population included in that diagnostic criterion.

Such biases need to be understood—as they can push estimates both up and down.

The authors rightly note that these quite critical international findings have largely been underplayed in our media and have not really reached our politicians. Who, if they understood the implications, would perhaps support more efforts for primary prevention at scale, including the research efforts in this area (Walsh et al., 2022). On a positive note, investment into initiatives such as the Gateway Exposome Coordinating Centre by the NIA should yield very valuable information for the increasing number of researchers interested in this area. Some risk and protective factors are “no-brainers” and there is already evidence supporting more work on intervention in this regard, aligned to healthy ageing itself (Walsh et al., 2023; Mukadam et al., 2024). The WHO Ageing focus and the Population Level Approaches to Dementia Risk Reduction are both working with life-course policy analysis to encourage such action (World Health Organization, 2022; Walsh et al., 2023).

References:

Stallard PJ, Ukraintseva SV, Doraiswamy PM. Changing Story of the Dementia Epidemic. JAMA. 2025 Mar 12; Epub 2025 Mar 12 PubMed.

Livingston G, Huntley J, Liu KY, Costafreda SG, Selbæk G, Alladi S, Ames D, Banerjee S, Burns A, Brayne C, Fox NC, Ferri CP, Gitlin LN, Howard R, Kales HC, Kivimäki M, Larson EB, Nakasujja N, Rockwood K, Samus Q, Shirai K, Singh-Manoux A, Schneider LS, Walsh S, Yao Y, Sommerlad A, Mukadam N. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. Lancet. 2024 Aug 10;404(10452):572-628. Epub 2024 Jul 31 PubMed.

Langa KM, Plassman BL, Wallace RB, Herzog AR, Heeringa SG, Ofstedal MB, Burke JR, Fisher GG, Fultz NH, Hurd MD, Potter GG, Rodgers WL, Steffens DC, Weir DR, Willis RJ. The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study: study design and methods. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25(4):181-91. PubMed.

Walsh S, Govia I, Wallace L, Richard E, Peters R, Anstey KJ, Brayne C. A whole-population approach is required for dementia risk reduction. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022 Jan;3(1):e6-e8. PubMed.

Walsh S, Wallace L, Kuhn I, Mytton O, Lafortune L, Wills W, Mukadam N, Brayne C. Population-level interventions for the primary prevention of dementia: a complex evidence review. Lancet. 2023 Nov;402 Suppl 1:S13. PubMed.

Mukadam N, Anderson R, Walsh S, Wittenberg R, Knapp M, Brayne C, Livingston G. Benefits of population-level interventions for dementia risk factors: an economic modelling study for England. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2024 Sep;5(9):100611. Epub 2024 Jul 31 PubMed.

World Health Organization. A blueprint for dementia research. World Health Organization, 4 October 2022 World Health Organization

Walsh S, Govia I, Peters R, Richard E, Stephan BC, Wilson NA, Wallace L, Anstey KJ, Brayne C. What would a population-level approach to dementia risk reduction look like, and how would it work?. Alzheimers Dement. 2023 Jul;19(7):3203-3209. Epub 2023 Feb 15 PubMed.

University of California, San Francisco

This is an interesting analysis and perspective. It's true that dementia prevalence and incidence appear to be declining with successive birth cohorts. There are many generational changes in risk factor profiles that may explain this, particularly improvements in education and management of chronic health conditions.

This analysis provides evidence to support our forecast from 2011, and subsequent Lancet Commission reports, which estimated that up to half of the anticipated increase in dementia due to the aging of the population could potentially be prevented through risk reduction interventions. This analysis suggests that we have made changes at a societal level that have fundamentally reduced dementia risk at a given age. They provide hope that ongoing and future efforts to target modifiable risk factors will result in continued reductions in dementia risk for younger generations.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.