Air Pollution and Dementia—Through Hazy Data, Links Emerge

Quick Links

Part 1 of 2

As coronavirus lockdowns have led to noticeably clearer skies above many metropolitan areas, people are beginning to wonder anew about the effects of air pollution. Traffic and industrial exhaust have long been linked to respiratory and cardiovascular disease, but far fewer studies have examined what this smog might do to the brain. That has begun to change. In PubMed, searching for “pollution and dementia” returned a paltry half-dozen papers for each year before 2014, but 51 for 2018, 56 for 2019, and 22 already in 2020, some of which are summarized below.

- The study of air pollution and dementia is gaining traction.

- Data points to neurodegeneration and cognitive decline.

- Researchers agree that more definitive studies are needed.

Overall, scientists are reporting that people with the highest exposures to pollutants are more likely to get dementia. Some of the risk may lie in chronic deterioration of the cardio- and cerebrovascular systems. Alas, researchers are finding that particulate matter can also get into the brain through olfactory nerves or across the blood-brain barrier, whereupon they may affect neurons and glia directly. Diffuse Aβ plaques, hyperphosphorylated tau, and aggregates of α-synuclein have been detected in olfactory bulbs in the brains of young people who lived in Mexico City, where air pollution is high.

Exhaust Smoke. Diesel trucks are a source of pollution in the United States.

Even countries with cleaner air may not entirely escape the problem. A report from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, entered into the Federal Register in January 2020, concludes that long-term exposure to fine particulate matter likely causes nervous system effects (see EPA Integrated Science Assessment for Particulate Matter).

With the field heating up, are epidemiologists ready to claim that air pollution increases a person’s risk for dementia? “I think we are comfortably suspicious. The toxicology suggests it is biologically plausible, but there’s a lot of diversity in the exposure and outcome data,” said Jennifer Weuve, Boston University School of Public Health.

Most epidemiologists Alzforum contacted were cautious. “Air pollution is similar to other risk factors,” said Melinda Power, George Washington University, Washington, D.C. “There is a signal that may be far from certain but [is] strong enough to warrant more attention.” In fact, an update to the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care will include pollution as one of the modifiable life-course risk factors, said Eric Larson at the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle. Larson co-wrote the original 2017 report that concluded that one-third of dementia cases are preventable (Aug 2017 conference news).

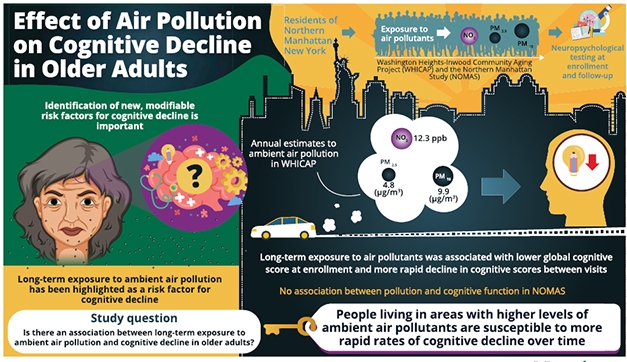

Pollution and Dementia. Evidence is growing that air pollution is a risk factor for cognitive decline. [Courtesy of Kulick et al., Neurology 2010 © American Academy of Neurology.]

Dirty Air and Dementia

What, then, is the data linking air pollution to dementia? Studies have correlated pollutant exposure with incident dementia, cognitive decline or, more recently, with brain imaging measures of degeneration (for example Zhang et al., 2019; Cacciotolo et al., 2017; Gatto et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2015; Power et al., 2018). For this, scientists measure pollutants directly from monitoring data gathered by the EPA and other government agencies, or indirectly by proximity of homes to major roads (Jan 2017 news). In a 2016 review, Power, Weuve, and colleagues identified 18 such studies; by May 13, 2020, while presenting at Brain Health and Air Pollution, a webinar organized by the Health Effects Institute, Weuve said that number was up to 48 (Power et al., 2016). Each study investigated common pollutants, including particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen oxides, wood smoke, and other airborne toxins for their effects on cognition, dementia, or neurodegeneration. Most report positive correlations.

That said, the findings are based on limited exposure and outcome data. Researchers therefore agree that they are tricky to interpret, much less extrapolate to the general population.

For example, linking exposure in the year prior to a person’s diagnosis of a disease such as Alzheimer’s, which has a decades-long prodrome, makes it difficult to infer causality, noted Power. “We need better studies that look at critical exposure windows,” she said. Comparisons are further complicated because different studies measure different types of pollution in different parts of the world. Selection bias and other confounds that frequently dog epidemiology can cloud air pollution research, too. The field is responding, however. “Some studies have begun to use complex methodologies to solve confounding and selection bias issues,” said Weuve.

Recently, researchers led by Erin Kulick at Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, correlated long-term exposure to air pollutants with cognitive scores among two cohorts in northeastern Manhattan. They reported their findings in the April 28 Neurology. Among 5,330 people in the longitudinal Washington Heights–Inwood Community Aging Project (WHICAP), which has been running since 1992, the scientists found the lowest cognitive scores at enrollment, and also the fastest decline, among participants living at addresses that had recorded the highest ambient levels of nitrogen dioxide, fine particulate matter, or respirable particulate matter in the year before they joined the study.

The researchers used a statistical method called inverse probability of censoring weights to account for dropouts. Attrition due to cognitive decline, or other illness caused by pollution, could dramatically skew the outcome. IPCW can account for that, which Weuve in an accompanying editorial called “a welcome undertaking in this line of inquiry.”

In the U.S. these air pollutants are regulated, hence they are continually monitored by the EPA Air Quality System. As defined, fine particulate matter measures less than 2.5 micrometers (PM2.5), while respirable particles measure less than 10 microns (PM10).

In contrast, Kulick and colleagues found no such correlation between NO2, PM2.5, or PM10 and cognition among 1,093 participants in the Northern Manhattan Study. NOMAS enrolled people who live in the same neighborhoods as those in WHICAP. What gives? NOMAS is smaller, participants were on average five years younger, and fewer of them had cardiovascular disease, which itself is linked to both air pollution and dementia. NOMAS enrolled 60 percent Hispanics, while WHICAP aims to have equal numbers of Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, and non-Hispanic white participants. These variables partly explain why one study found a correlation and one did not.

Alas, there is more to it. Illustrating the challenges epidemiologists face in studying air pollution, the calculated exposures in the two studies were not quite the same, despite the studies’ overlapping postal codes. While WHICAP and NOMAS had similar mean levels of exposure to NO2—31.9 and 30.5 parts per billion (ppb), respectively—their interquartile ranges were 12.3 versus 3.2 ppb. The IQR represents the “sweet spot” covering the middle half of the data and eliminates outliers that might cause spurious effects. When this range is narrow, as in the NOMAS data, it can be difficult to estimate associations with other variables, noted Weuve.

One caveat is that one-year measures may not reflect a participant’s lifetime exposure. This is especially important because air pollution levels in the U.S. have declined steadily since the Clean Air Act was passed in 1970. What was their exposure in middle age, for example, when other risk factors, including hypertension, appear to strongly influence the risk of future dementia?

To address when in a person’s life exposure may be important for future dementia, researchers are tapping broader historical sampling of air pollution. Lianne Sheppard, University of Washington, Seattle, is collaborating with Larson to examine the effects of pollution in the Adult Changes in Thought study. ACT has been assessing cognition in volunteers 65 and older around the state’s Puget Sound since 1994; separately, the EPA started monitoring air pollution in this area in the 1980s. Sheppard is using the EPA data to calculate long-term exposure and to correlate it with cognitive decline, dementia incidence, neuropathology, and potentially other variables such as co-morbidities and prescription medication in the ACT participants.

Similarly, Power is using data from the Atherosclerosis Risks in Community study to correlate long-term exposure to air pollution with similar cognition, dementia, and pathology measures. A prospective examination of causes and consequences of atherosclerosis, ARIC had been gathering data in four communities in Maryland, Minneapolis, Mississippi, and North Carolina since 1987. Power hopes to include amyloid biomarker data, as well, to distinguish a specific Alzheimer’s disease etiology from all-cause dementia.

For her part, Weuve has begun to correlate long-term air pollution exposures, as per EPA data and hundreds of private monitors installed by collaborators from the University of Washington, with dementia and biomarkers in seven different longitudinal observational cohorts around the Chicago area: the Memory and Aging Project; the Religious Orders Study; the Minority Aging Research Study; the Latino CORE Study; the Clinical Core study; Parent Offspring Resilience and Cognitive Health; and the Chicago Health and Aging Project. These well-characterized cohorts undergo regular cognitive assessments and include neuropathology.

Such data seem promising. In the January issue of Brain, researchers led by Jiu-Chiuan Chen at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, correlated PM2.5 exposure with memory deficits. They report that the relationship was mediated, in part, by an Alzheimer’s-like regional pattern of atrophy seen on MRI scans. Co-first authors Diana Younan, Andrew Petkus, and colleagues studied 998 volunteers in the Women’s Health Initiative. Each had undergone two MRI scans four years apart, plus annual cognitive testing. The researchers correlated these measures with three-year PM2.5 levels at their homes drawn from environmental air-quality measures. “It seems that air pollution may alter brain structure, and that then leads to memory problems,” Younan told Alzforum. “We were trying to see the pathway that leads to brain deficits.”

Because the WHI began in 1996, before PET and CSF measures of amyloid and tau were established, Chen and colleagues relied on an AD-pattern-similarity tool devised by Mark Espeland and colleagues at Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (Casanova et al., 2011). It uses machine learning to score MRI patterns for similarity to those seen in people with AD.

Similarly, researchers led by Jose Luis Molinuevo at the Barcelonaβeta Brain Research Center in Spain correlated ambient air pollution with cognition and brain atrophy among people in the Alzheimer and Families cohort. ALFA is a prospective study of middle-aged people, many from families with a history of AD. In the March 6 Environment International, first author Marta Crous-Bou and colleagues reported that higher exposure to NO2 and PM10 weakly correlated with thinner cerebral cortices among 228 participants, average age 58. The regions affected were those known to atrophy in AD, including entorhinal, inferior and middle temporal, fusiform, posterior cingulate, precuneus, and supramarginal gyri.

Taking a bird’s-eye view of brain effects, researchers led by Shawn Gale and Dawson Hedges at Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, spotted an ambient air pollution effect among 18,292 people, average age 62, who are being tracked in the U.K. Biobank study. In the March 13 Brain Sciences, first author Lance Erickson and colleagues detailed how higher PM2.5 correlated with lower white-matter volume on MRI. PM2.5, and also PM10, NO, and NO2, all correlated with less gray matter, as well. The U.K. Biobank aims to capture MRI scans of 100,000 people and rescan 10 percent of them. This ambitious project has collected data on 500,000 registrants in hopes of understanding causes and correlates of disease of aging. It gathers air pollution data at the neighborhood level, as well as participant self-reports of time spent outdoors, which helps improve exposure estimates (Sudlow et al., 2015).

Initial results suggest that air pollution, at least at levels seen in the U.K., has a weak effect on cognition over the short term. Breda Cullen and colleagues at the University of Glasgow reported that among 86,759 participants, average age 58, air pollution measured at one time up to five years before baselineF poorly correlated with cognitive measures at baseline and after an average of 2.8 years of follow-up once they adjusted for other variables such as age, gender, physical activity, and population density (Cullen et. al., 2018).

All told, links between ambient air pollution and dementia seem to be strengthening, said Caleb (Tuck) Finch, University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Finch calls air pollution a gerogen. “It accelerates aging, weakens blood vessels in the brain, and promotes amyloid production,” he told Alzforum. “The argument that air pollution is a risk factor for dementia is doubly strong because it also accelerates atherosclerosis, which is a risk factor independently of everything else,” he said. Finch estimates that air pollution could account for 10 percent of dementia cases worldwide. “By continuing to burn fossil fuels we are promoting a global health hazard,” he said. For more on how airborne pollutants might wreak havoc on the brain, see Part 2 of this story.—Tom Fagan

References

News Citations

- Lancet Commission Claims a Third of Dementia Cases Are Preventable

- Dementia Risk Ticks Up Near Major Roadways

- The Air We Breathe—How Might Pollution Hurt the Brain?

Paper Citations

- Zhang HW, Kok VC, Chuang SC, Tseng CH, Lin CT, Li TC, Sung FC, Wen CP, Hsiung CA, Hsu CY. Long-Term Exposure to Ambient Hydrocarbons Increases Dementia Risk in People Aged 50 Years and above in Taiwan. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2019;16(14):1276-1289. PubMed.

- Cacciottolo M, Wang X, Driscoll I, Woodward N, Saffari A, Reyes J, Serre ML, Vizuete W, Sioutas C, Morgan TE, Gatz M, Chui HC, Shumaker SA, Resnick SM, Espeland MA, Finch CE, Chen JC. Particulate air pollutants, APOE alleles and their contributions to cognitive impairment in older women and to amyloidogenesis in experimental models. Transl Psychiatry. 2017 Jan 31;7(1):e1022. PubMed.

- Gatto NM, Henderson VW, Hodis HN, St John JA, Lurmann F, Chen JC, Mack WJ. Components of air pollution and cognitive function in middle-aged and older adults in Los Angeles. Neurotoxicology. 2014 Jan;40:1-7. Epub 2013 Oct 19 PubMed.

- Chen JC, Wang X, Wellenius GA, Serre ML, Driscoll I, Casanova R, McArdle JJ, Manson JE, Chui HC, Espeland MA. Ambient air pollution and neurotoxicity on brain structure: Evidence from women's health initiative memory study. Ann Neurol. 2015 Sep;78(3):466-76. Epub 2015 Jul 28 PubMed.

- Power MC, Lamichhane AP, Liao D, Xu X, Jack CR, Gottesman RF, Mosley T, Stewart JD, Yanosky JD, Whitsel EA. The Association of Long-Term Exposure to Particulate Matter Air Pollution with Brain MRI Findings: The ARIC Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2018 Feb 16;126(2):027009. PubMed.

- Power MC, Adar SD, Yanosky JD, Weuve J. Exposure to air pollution as a potential contributor to cognitive function, cognitive decline, brain imaging, and dementia: A systematic review of epidemiologic research. Neurotoxicology. 2016 Sep;56:235-253. Epub 2016 Jun 18 PubMed.

- Casanova R, Whitlow CT, Wagner B, Williamson J, Shumaker SA, Maldjian JA, Espeland MA. High dimensional classification of structural MRI Alzheimer's disease data based on large scale regularization. Front Neuroinform. 2011;5:22. PubMed.

- Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, Beral V, Burton P, Danesh J, Downey P, Elliott P, Green J, Landray M, Liu B, Matthews P, Ong G, Pell J, Silman A, Young A, Sprosen T, Peakman T, Collins R. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015 Mar;12(3):e1001779. Epub 2015 Mar 31 PubMed.

- Cullen B, Newby D, Lee D, Lyall DM, Nevado-Holgado AJ, Evans JJ, Pell JP, Lovestone S, Cavanagh J. Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses of outdoor air pollution exposure and cognitive function in UK Biobank. Sci Rep. 2018 Aug 14;8(1):12089. PubMed.

External Citations

Further Reading

Papers

- Gale SD, Erickson LD, Anderson JE, Brown BL, Hedges DW. Association between exposure to air pollution and prefrontal cortical volume in adults: A cross-sectional study from the UK biobank. Environ Res. 2020 Jun;185:109365. Epub 2020 Mar 11 PubMed.

- Wilker EH, Preis SR, Beiser AS, Wolf PA, Au R, Kloog I, Li W, Schwartz J, Koutrakis P, DeCarli C, Seshadri S, Mittleman MA. Long-term exposure to fine particulate matter, residential proximity to major roads and measures of brain structure. Stroke. 2015 May;46(5):1161-6. PubMed.

- Hedges DW, Erickson LD, Gale SD, Anderson JE, Brown BL. Association between exposure to air pollution and thalamus volume in adults: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2020;15(3):e0230829. Epub 2020 Mar 30 PubMed.

- Hedges DW, Erickson LD, Kunzelman J, Brown BL, Gale SD. Association between exposure to air pollution and hippocampal volume in adults in the UK Biobank. Neurotoxicology. 2019 Sep;74:108-120. Epub 2019 Jun 17 PubMed.

Primary Papers

- Kulick ER, Wellenius GA, Boehme AK, Joyce NR, Schupf N, Kaufman JD, Mayeux R, Sacco RL, Manly JJ, Elkind MS. Long-term exposure to air pollution and trajectories of cognitive decline among older adults. Neurology. 2020 Apr 28;94(17):e1782-e1792. Epub 2020 Apr 8 PubMed.

- Younan D, Petkus AJ, Widaman KF, Wang X, Casanova R, Espeland MA, Gatz M, Henderson VW, Manson JE, Rapp SR, Sachs BC, Serre ML, Gaussoin SA, Barnard R, Saldana S, Vizuete W, Beavers DP, Salinas JA, Chui HC, Resnick SM, Shumaker SA, Chen JC. Particulate matter and episodic memory decline mediated by early neuroanatomic biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2020 Jan 1;143(1):289-302. PubMed.

- Crous-Bou M, Gascon M, Gispert JD, Cirach M, Sánchez-Benavides G, Falcon C, Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Gotsens X, Fauria K, Sunyer J, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Luis Molinuevo J, ALFA Study. Impact of urban environmental exposures on cognitive performance and brain structure of healthy individuals at risk for Alzheimer's dementia. Environ Int. 2020 May;138:105546. Epub 2020 Mar 6 PubMed.

- Erickson LD, Gale SD, Anderson JE, Brown BL, Hedges DW. Association between Exposure to Air Pollution and Total Gray Matter and Total White Matter Volumes in Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Brain Sci. 2020 Mar 13;10(3) PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.