CONFERENCE COVERAGE SERIES

Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting 2013

San Diego, CA, U.S.A.

09 – 13 November 2013

CONFERENCE COVERAGE SERIES

San Diego, CA, U.S.A.

09 – 13 November 2013

Researchers interested in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and other disorders of RNA arrived early for the Society for Neuroscience annual meeting this year, attending “RNA Metabolism in Neurological Disease,” a two-day satellite symposium held November 7-8 in San Diego. To facilitate cross-fertilization among researchers studying different kinds of repeat disorders and RNA metabolism pathology, meeting organizers Paul Taylor of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and Fen-Biao Gao of the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester invited speakers studying a range of conditions. Gao told Alzforum he was glad to see attendance up from the last RNA meeting in 2011 (see Nov 2011 conference story), with nearly 300 attendees.

About one-third of the more than 30 genes linked to ALS affect RNA metabolism, either directly or indirectly, said Robert Brown of the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester, who opened the conference with an overview of genetics. Many attendees were excited about recent results in the study of the C9ORF72 gene. C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat expansions are the most common cause of familial ALS and frontotemporal dementia. Scientists discussed how the repeat size correlates with disease presentation, various up-and-coming animal models, and potential treatment strategies. Antisense oligonucleotides were recently tested in disease models as one possible treatment strategy (see Oct 2013 news story; news story). Christopher Pearson of The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto suggested another, based on destabilizing G-quadruplex structures that the repeat likely assumes.

Pearson and others noted that ALS and FTD researchers benefit from previous studies of more than 40 other nucleotide repeat disorders, such as myotonic dystrophy, from which they can mine hypotheses and techniques. For example, repeat associated non-ATG (RAN) translation, identified for C9ORF72 earlier this year, was found first in other diseases (see Feb 2013 news story, news story). Laura Ranum of the University of Florida in Gainesville, who originally described this unusual translation, welcomed C9ORF72 researchers to the fold (Zu et al., 2011). “The RAN translation field has been pretty lonely,” she said.

A Stable Shape for C9ORF72 RNA Foci?

Scientists have established that C9ORF72 forms stable RNA foci, with aggregates forming out of RNA in both the sense and antisense direction (see Nov 2013 news story). How might the GGGGCC repeats tangle together? Pearson presented results, released over the last year by his group and others, that suggest the sense RNA forms a stable structure called a G-quadruplex (see Sep 2012 news story, Reddy et al., 2013, Fratta et al., 2013).

Stabilizing Expansions

G-quadruplexes are formed of stacks of square G-quartets, with guanines at each corner, surrounding a positive ion. The DNA or RNA strands forming the edges can be parallel or antiparallel, as shown here, and come from the same nucleic acid chain (as shown) or multiple chains. Nucleotides that are not guanines hang off the structure in the external loops. [Image courtesy of Julian Huppert, Wikimedia Commons.]

G-quadruplexes form naturally from guanine-rich sequences of single-stranded DNA or RNA. Four guanines interact around a positive ion, making a square called a G-quartet, and these stacked squares make up a quadruplex. An individual nucleic acid strand may form a quadruplex, or multiple strands may come together to create it. G-quadruplexes appear throughout biology. For example, unimolecular G-quadruplexes show up in the single-stranded telomeric DNA at the ends of chromosomes, and in oncogene promoters when they unwind DNA (reviewed in Chen and Yang, 2012). In RNA, G-quadruplexes are common in 5’ untranslated sequences and affect translation (reviewed in Bugaut and Balasubramanian, 2012).

Given the guanine-rich nature of the C9ORF72 repeat sequence, Pearson suspected it might form a G-quadruplex. Using circular dichroism, Kaalak Reddy and colleagues in Pearson's lab showed this was the case for repeats of two to eight GGGGCC sequences in RNA in vitro. The structures formed out of multiple RNAs, with the backbones of the RNA at each corner of the quadruplex lined up in parallel. The G-quadruplexes were highly stable, and did not melt completely even at 95 degrees Celsius.

Researchers suspect that C9ORF72 expanded RNA forms these structures in vivo, though it would be difficult to prove, Pearson told Alzforum. He also found that some RNA-binding proteins, such as hnRNPA1, interact with C9ORF72 quadruplexes in vitro. The antisense version of the expanded RNA (GGCCCC), which researchers recently found transcribed in cells expressing expanded C9ORF72, would be more likely to form a hairpin, he predicted.

If RNA foci comprising G-quadruplexes prove to be toxic, then drugs that bind the quadruplex backbone might do some good, Pearson reasoned. Researchers have already developed some small molecules that interact with the quadruplexes (reviewed in Neidle, 2010). Pearson and colleagues tested one such compound on C9ORF72 G-quadruplexes in vitro (see Siddiqui-Jain et al., 2002; Monchaud et al., 2010; Faudale et al., 2012). TMPyP4—which stands for the mouthful tri-meso(N-methyl-4-pyridyl), meso(N-tetradecyl-4-pyridyl) porphine—looks like a four-pronged “ninja star,” Pearson said, that can stick to the squares of G-quadruplexes. He found it bound C9ORF72 G-quadruplexes and destabilized them. It also interrupted the interaction between the quadruplex and RNA-binding proteins such as hnRNPA1, he reported.

Brown said Pearson’s ideas should be tested in cells and animals as soon as possible. However, Pearson was careful to caution that he does not propose TMPyP4 as a treatment for human disease, but rather presents the results as a proof of principle that a small molecule can alter the structure of C9ORF72 RNA foci. For one, he pointed out, researchers are not yet certain if RNA foci are the pathological cause of C9ORF72 disease. For another, TMPyP4 binds several kinds of G-quadruplexes, not just the GGGGCC sequence, and he does not yet know if it binds C9ORF72’s sequence preferentially.

C9ORF72 Genetics

While Pearson worked with a handful of repeats in vitro, in people the expansion can grow to considerable lengths. Marka van Blitterswijk and colleagues in Rosa Rademakers' lab at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, have characterized the repeat size in different tissues of individuals who carry the expansion. As Rademakers’ lab reported previously, the number of repeats varies widely among expansion carriers and even among tissues within the same person (see Jan 2013 conference story). Van Blitterswijk and colleagues used Southern blots to measure repeat sizes in 84 expansion carriers with FTD, motor neuron disease, or both, as well as some asymptomatic carriers, from a range of tissues including blood, cerebellum, and frontal cortex, as she presented in a poster and Rademakers showed in a slide presentation (see Van Blitterswijk et al., 2013). Overall, the cerebellum tended to have the shortest average repeat length, 1,667, compared with 5,250 in frontal cortex. The expansion size failed to predict whether someone had FTD versus ALS. Blood repeat size, with an average of 2,717, correlated with neither brain repeat length nor disease severity. Pearson said this was disappointing from a clinical point of view, because it precludes predicting disease course with a simple blood test for expansion size. However, blood testing can still identify or exclude someone as an expansion carrier, Van Blitterswijk noted.

Van Blitterswijk and others have reported that C9ORF72 expansion carriers may have second mutations that could contribute to pathology, and perhaps even explain why one carrier gets FTD while another has ALS (see Jan 2013 conference story; Van Blitterswijk et al., 2012; Van Blitterswijk et al., 2013). In San Diego, Rademakers reported genotyping C9ORF72 carriers for a rare variant in the gene TMEM106B, a protective factor against FTD in carriers of progranulin mutations (see Feb 2010 news story; Finch et al., 2011; Aug 2012 news story). Among more than 300 expansion carriers, Van Blitterswijk observed a lower-than-normal frequency of homozygotes for the minor allele, but this pattern occurred only in those with FTD. The protective, minor allele appears to stave off FTD, but not ALS, she suggested.

TMEM106B is the first genetic modifier of C9ORF72 to be identified, Rademakers noted. Brown agreed. “It looks like it is a real modifier,” he said. Van Blitterswijk speculated that because TMEM106B influences lysosome shape and activity, genetic variants might affect degradation and aggregation of TDP-43, which could influence FTD risk.

Animal Models Under Construction

Since the discovery of the C9ORF72 gene’s link to disease in 2011 (see Sep 2011 news story), researchers have started to develop a number of experimental models to study the expansion. Gao, Christopher Donnelly of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and Clotilde Lagier-Tourenne of the University of California, San Diego, described published models of cultured primary fibroblast and induced pluripotent stem cell lines from C9ORF72 expansion carriers (see Almeida et al., 2013). In San Diego, researchers reported progress with several new whole-animal models. The creatures are difficult to create, scientists told Alzforum, due to the unstable nature of the repeated sequence.

Brian Freibaum of St. Jude and Helene Tran of the University of Massachusetts in Worcester reported introducing C9ORF72 into fruit flies, which have no homolog to the human gene. Freibaum expressed C9ORF72 with eight, 28, and 58 repeats (the cutoff between health and disease appears to be about 30) and looked for RNA aggregates and peptides due to translation of the repeat sequence, both of which are subjects of intensive research. At eight repeats, he saw neither. At 28, he observed RNA foci. At 58, he saw both RNA foci and peptide aggregates. The 28-repeat construct might be “on the cusp” of RAN translation, Freibaum speculated. The longer constructs were toxic when expressed in various fly tissues. For example, flies transcribing C9ORF72 with 28 or 58 repeats in muscle tissue held their wings awkwardly up or down, instead of flat like wild-type animals.

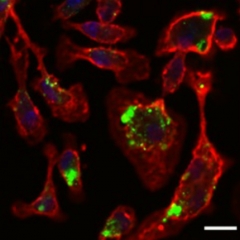

Peptides RAN amok in flies

A proline-glycine poly-dipeptide (green) born of RAN translation of C9ORF72 aggregates in the muscles of transgenic Drosophila. Image courtesy of Brian Freibaum, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tennessee.

Tran engineered flies with a range of repeat lengths. Those with 160 repeats accumulated RNA aggregates, climbed poorly, and died earlier than flies with only five repeats. Both Tran and Freibaum are conducting screens for genetic suppressors and enhancers of the C9ORF72 phenotype in their models. These screens could identify genes involved in disease progression and potential drug targets, Freibaum told Alzforum. The repeats also caused neurodegeneration in a fly model published earlier this year (see Xu et al., 2013).

Focus on Flies

In a Drosophila model of C9ORF72 with 160 repeats, fluorescence in-situ hybridization identifies RNA foci (red) in the ventral nerve cord of larvae (blue=nuclei). Image courtesy of Helene Tran, University of Massachusetts, Worcester.

Vertebrate C9ORF72 models are also making headway. Bettina Schmid of the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE) in Munich presented preliminary results from zebrafish models. Schmid created knockout animals and fish that express two or 80 repeats in the zebrafish homolog of the human gene. Knockout models should help identify the natural function of C9ORF72, which is unknown, Schmid told Alzforum. However, her knockouts had no obvious phenotype. “They swim and grow normally,” Schmid said. Another group recently reported that zebrafish C9ORF72 knockouts swam poorly. The difference could be due to different knockout technology used by the two groups, Schmid speculated (see Ciura et al., 2013). In Schmid’s expansion models, two repeats elicited no RNA foci or peptide aggregates, whereas 80 repeats created both. Schmid says she needs to confirm these preliminary results.

No C9ORF72, No Problem

Motor neuron axon length was the same between wild-type and C9ORF72 knockout zebrafish embryos in these sections stained with an antibody to znp-1. Image courtesy of Alexander Hruscha, German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases, Munich.

Finally, both Brown and Lagier-Tourenne discussed mouse models. They and several other researchers are part of a large collaboration, working with C9ORF72 bacterial artificial chromosomes provided by the ALS Association. Brown described a mouse engineered to have 600 repeats which has now reached 11 months old and produced three further generations. It has no obvious motor phenotype, he reported. The animals gain weight normally and grip and balance on a rotating rod just like wild-type mice. However, Brown believes the animals will be useful because they accumulate RNA foci and RAN-translated dipeptides, as collaborators in Gao’s lab and Leonard Petrucelli's lab at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville have found. Lagier-Tourenne and Don Cleveland at the University of California, San Diego, have created several mouse lines, with repeats ranging from 100 to 450. They plan to test antisense oligonucleotide treatments in those mice.

Brown also reported on a C9ORF72 knockout model created by Kevin Eggan of Harvard University. These mice are about a year old, and the researchers have observed a subtle but progressive loss of motor function, including denervation of muscles, paralysis, and early death. These data support the theory that C9ORF72 disease results from haploinsufficiency of the gene, commented Aaron Gitler of Stanford University in Palo Alto, California. Lucie Bruijn from the ALS Association said that all these models would be useful and complementary.

Future Questions

Researchers at this meeting agreed that they have only started to untangle the effects of C9ORF72 expansions. “Much more needs to be understood at the mechanistic level,” Gao told Alzforum. “We know so little.” Some data support loss of C9ORF72 function as a problem, but what about RNA foci and RAN-translated peptides—“Are they pathogenic, or are they a parlor trick?” asked Brown. He said for now data seem to indicate that silencing C9ORF72 would be beneficial, and Bruijn agreed this would be her priority treatment approach.—Amber Dance

Several proteins linked to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia show up in stress granules. These natural RNA-protein accumulations protect essential RNAs in times of cellular strife, but cause trouble if they fail to dissipate when the good times return. Stress granules have become a major theme in the study of ALS and related disorders, Robert Brown of the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester noted when he gave the opening address at “RNA Metabolism in Neurological Disease,” a symposium held November 7–8 in San Diego. Researchers have observed disease-associated mutants of TDP-43, FUS, hnRNPA1, hnRNPA2, and ataxin-2 all mired in pathological stress granules. Unexpectedly, Aaron Gitler and Matthew Figley of Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, added another ALS gene to the list: profilin-1, an actin-binding protein. Profilin-1 associates with stress granules in yeast and in mammal cell lines, they reported.

Gitler said he has come to think of stress granules as “crucibles of ALS pathogenesis” because their failure to disassemble may promote neurodegeneration (see Li et al., 2013 and reviewed in Wolozin, 2012). He and Figley offered their results in an oral presentation and poster, respectively.

They did not expect to find themselves studying stress granules when they followed up on the identification of profilin-1 as an ALS gene. ALS-linked profilin-1 mutations occur in the protein’s actin-binding domain, leading researchers to suspect that defects in actin filament assembly or axon outgrowth predispose to the disease, but the mechanism remains a mystery. To get a handle on it, Figley, who works in Gitler’s lab, studied the yeast version of profilin-1, PFY1, which also interacts with actin.

Yeasts that lack PFY1 or express a mutated variant grow at 30 degrees Celsius, but, unlike wild-type yeast, they are inviable at 37 degrees. Adding the human profilin-1 gene allowed the cells to tolerate the higher temperature, reported Figley. He reasoned that he could use the yeast system to assess the functionality of various human profilin-1 variants. The cysteine-71-glycine and methionine-114-threonine substitutions, for example, failed to rescue the deletion strain, whereas the glutamate-117-glycine mutation did, indicating that the first two mutations are fully inactive while E117G might retain some function. This lines up neatly with human results. People with the E117G substitution have no sign of disease, leading scientists to suspect it creates a less severe defect than the C71G and M114T mutations, which turned up only in ALS cases in the original study (see Jul 2012 news story).

To understand profilin’s natural role in yeast, Figley created a set of strains with mutations in PFY1 plus one other gene—for a total of 4,800 crosses—and looked for double mutants that failed to grow. The screen identified three categories of genes that interact with PFY1. One comprised those involved in actin and actin-related cellular activities—no great surprise there. Another consisted of genes related to dynactin, which helps drive intracellular transport. This was interesting, Gitler said, because profilin-1 had no prior link to dynactin. The multipart dynactin complex helps dynein tote cellular cargo along microtubules, and mutations in dynactin components have been linked to motor neuron disease (see Münch et al., 2004; Münch et al., 2005). What was surprising to Gitler and Figley was the third, noncytoskeleton category of genes. About 10 percent of the hits related to stress granules or P-bodies, which are similar mRNA aggregates. Might profilin-1 be important for stress granule formation? To test this hypothesis, Figley stressed various cell types and looked for profilin-1 in the RNA foci.

The researchers treated HeLa cervical cancer cultures with arsenite or dithiothreitol, and observed that profilin-1 co-localized with ataxin-2 and Hu protein R, another stress granule marker. Treatment with cyclohexamide, which prevents RNA from forming into stress granules, prevented the profilin-1 foci (see image below). The same pattern occurred in the human osteosarcoma line U2OS, and in primary mouse cortical neurons. A heat shock also redistributed profilin-1 to RNA foci in the primary neural line. Gitler and Figley concluded that the profilin-1 foci were likely to be stress granules.

Profiling Stress

In primary cortical mouse neurons under duress, profilin-1 (green) co-localized with the known stress granule marker ataxin 2 (red).

The researchers still need to work out how profilin-1 mutations affect stress granules in ALS. The researchers are collaborating with Paul Taylor at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, to video granule assembly and disassembly in living cells and sort out how profilin-1 might contribute to motor neuron degeneration. Thus far, ALS-linked profilin-1 mutants appear to accumulate in abnormal RNA aggregates, Gitler said.

Ben Wolozin of Boston University said that in hindsight, he did not find it so surprising that profilin-1 might participate in stress-granule formation. When those structures form, they must rely on the cytoskeleton to deliver components; similarly, the cytoskeleton must pull the granules apart when the RNAs are needed again, he reasoned. He speculated that profilin-1 loss-of-function mutants might be unable to disassemble stress granules, causing long-lasting, pathological granules to accumulate.

Overall, the idea of pathological stress granules has become widely accepted, Wolozin said. Treatments to dissolve pathological stress granules could have therapeutic potential, he added.—Amber Dance.

No Available Comments

As misfolded proteins corrupt their natively folded counterparts, many neurodegenerative diseases spread from one part of the brain to the next in a predictable fashion. To take a crack at formally categorizing this sequence for the neuropathology of TDP-43, Virginia Lee of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia presented a four-part staging scheme at “RNA Metabolism in Neurological Disease,” a conference held November 7-8 in San Diego. “We can add ALS to the growing list of neurodegenerative diseases where the pathology spreads in a stereotypical manner,” said Lee. Published last July, the scheme should help clinicians and researchers classify pathology at autopsy, much as Braak staging has done for Alzheimer’s disease (Brettschneider et al., 2013). That pathology progresses in a defined pattern also indicates a potential therapeutic avenue: treatments that block TDP-43 spread might freeze disease at an early stage, suggested Robert Brown of the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester, who was not involved with the work.

Misfolded Aβ, tau, and α-synuclein all spread from cell to cell in the brain in predictable patterns. Might TDP-43 do the same? Studies indicate that misfolded TDP-43 infiltrates cells in culture and seeds new misfolding and aggregation (see Apr 2011 news story; Nonaka et al., 2013). To find out if brain pathology supports a cell-to-cell pathway, Johannes Brettschneider from the University of Ulm, Germany, analyzed human autopsy tissue in a study begun while he was on sabbatical in the laboratory of John Trojanowski at UPenn. Brettschneider continued the work in Ulm along with co-first author Kelly Del Tredici and co-senior author Heiko Braak.

Brettschneider examined the brains and spinal cords from 76 people who died of ALS. The researchers did not examine brains of ALS patients who died early in the disease of other causes. People with ALS typically die when their diaphragm no longer supports breathing unless they use a respirator; this can happen at different stages of disease, so the scientists believe their sample reflects various degrees of severity of ALS. They found that TDP-43 antibodies bound dash-, dot-, and skein-shaped inclusions in the cytoplasm of neurons and oligodendrocytes. Based on the patterns of these aggregates, the researchers defined four different stages.

Stage 1 cases exhibited TDP-43 aggregates only in the motor cortex, brainstem, and spinal cord. In stage 2, aggregates also dotted the prefrontal neocortex, precerebellar nuclei, and the red nucleus, a midbrain structure involved in motor control. By stage 3, TDP-43 pathology spread to the postcentral neocortex and striatum. In those few people who reached stage 4, the pathology also occurred in the temporal lobe. Overall, TDP-43 pathology appears to start in the motor cortex at the top of the brain and radiate downward to the spinal cord, as well as forward to the frontal cortices.

Since autopsy tissue provides only a static snapshot, the precise directionality of any TDP-43 transfer remains uncertain, Trojanowski said. Presumably, TDP-43 turns bad at a single point and spreads from there, Trojanowski speculated, via axons (reviewed in Braak et al., 2013).

Eleven of the people in the study had ALS due to a repeat expansion in the C9ORF72 gene. Brettschneider and colleagues noted that in those cases, the direction of spread was the same, but the density of TDP-43 lesions was greater at any given stage. This makes sense, Trojanowski said, since doctors have observed that C9ORF72 expansions create a more aggressive disease.

“It is a useful construct for understanding the [progression] of disease in the brain,” commented Brown, who called the paper “brilliant.” Even so, researchers at the meeting agreed there is more work to be done. Brown would like to see more details on TDP-43 spread in the spinal cord, because ALS is a disease primarily of spinal motor neurons, not the brain. Trojanowski said the scientists are now taking a closer look at spinal-cord pathology. They also are examining frontotemporal dementia cases to complement the ALS work, because TDP-43 proteinopathy can cause either condition or a combination of the two. That prefrontal cortex pathology was a regular feature of the ALS cases in this study could explain why cognitive dysfunction is a common symptom, the authors suggest.

Staging systems provide a useful shorthand for clinical researchers, Trojanowski said. Instead of describing dozens of places where pathology occurs, they can label a case by stage and easily communicate the extent of disease. In living persons, there is no sure way to identify stages; rather, physicians typically estimate what stage a patient is at by assessing their symptoms and deducing which brain areas are likely affected. This could prove useful if someday there are different treatments appropriate to different stages, Brown speculated.

The predictable spread of TDP-43 indicates that this misfolded protein, like others, transfers pathology down the axon and across synapses through connected neural networks. Scientists are actively working on tracing this cell-to-cell spread in animal models, as has been done already for Aβ, tau and α-synuclein (see Jul 2012 news story; Jun 2009 news story; Mougenot et al., 2011).

“The evidence of cell-to-cell spread is transformative in how we think of therapy,” Trojanowski said. An extracellular antibody to each protein might halt that spread, effectively isolating the pathology in one part of the nervous system. Scientists are already testing this new kind of passive immunotherapy in tauopathy (see Aug 2013 news story), and Trojanowski suggests a similar treatment could work for TDP-43 proteinopathy as well.—Amber Dance.

No Available Comments

Researchers are taking aim at amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with an antisense oligonucleotide targeted toward microRNA (miRNA), those nucleic acid snippets that each regulate hundreds of mRNAs. A single anti-miRNA therapeutic could tune a whole network of genes, suggests Erica Koval of Washington University in St. Louis. She presented preclinical data on anti-miR-155 at “RNA Metabolism in Neurological Disease,” a meeting held November 7–8 in San Diego. Koval reported that blocking miR-155 in mouse models of ALS slowed disease progression. Koval, senior author Timothy Miller, and colleagues published some of the findings last month (Koval et al., 2013).

Anti-microRNA therapy has been tested for conditions including hepatitis, stroke, and cancer (Janssen et al., 2013; Buller et al., 2010; Abba et al., 2012), but Koval believes she is the first to try it for a neurodegenerative condition. Anti-miRNA oligonucleotides work a bit differently than standard antisense molecules aimed at much larger mRNAs. While the latter destroy the mRNA target, anti-microRNAs simply bind to their targets, preventing them from interacting with the mRNAs they regulate. Koval and Miller collaborated with Regulus Therapeutics of San Diego, a spinoff of Isis Pharmaceuticals of Carlsbad, California. Isis develops traditional anti-mRNA treatments, including an antisense therapy for the ALS gene superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) in collaboration with Miller and others (see May 2013 news story). Regulus focuses on anti-microRNAs.

At the start of the project, Koval and colleagues predicted that microRNAs would be dysregulated in ALS, and that correcting the dysregulation might help. Using microarrays, she identified 12 microRNAs that were upregulated in mouse and rat models of ALS, compared to control animals. Of these, six were also upregulated in the spinal cords of people who had died of ALS, according to Koval’s analysis of autopsy tissues. No microRNAs were significantly downregulated. Koval chose to focus on miR-155 first, because levels were doubled in spinal cords from people who had either familial or sporadic ALS, indicating a common problem. Researchers already knew that MiR-155 promotes neuroinflammation (O’Connell et al., 2010), a key feature of ALS pathology (see Boillée et al., 2006; Sep 2008 news story), and Regulus already had an antisense molecule ready to evaluate in animals.

MiR-155’s targets include mRNAs for these genes:

Because the blood-brain barrier prevents microRNAs from entering the central nervous system (CNS), Koval delivered a constant stream of anti-miR-155 directly into mouse brain lateral ventricles using a micropump. Tracking the fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide, she saw that it entered neurons and glia throughout the brain and spinal cord of wild-type mice (see figure below). She also confirmed that the two-week treatment derepressed miR-155 target mRNAs; levels of SHIP1, PU.1, CARD11, and CYR61 mRNA all rose.

Infused into the lateral ventricles of mice, Cy5-labeled anti-miR-155 (red), infiltrated neurons (top) , microglia (middle), and astrocytes (bottom) labeled with antibodies (green) to NeuN, Iba1, and GFAP, respectively. Image courtesy of Erica Koval, Washington University in St. Louis.

“It is fantastic how well these things get into the nervous system,” commented Peter Nelson of the University of Kentucky in Lexington, who was not involved in the work. “Anti-microRNA provides such a ready opportunity for treatment.” Nelson speculated that neurons might take up the oligonucleotides by some sort of active mechanism.

Next, Koval tried the anti-miR-155 treatment in an ALS mouse model that expresses mutant human SOD1. She was uncertain if cells in the CNS, peripheral immune cells infiltrating the CNS, or both might be involved in any possible benefits. Notably, peripheral macrophages undergo activation in ALS (see Nov 2009 news story). To maximize her chances of treating the disease, Koval combined administration to the brain lateral ventricles with weekly peripheral injections. She began treatment when the mice were 60 days old, about 40 days before symptoms of disease—weight loss and paralysis—normally emerge. Disease onset was unchanged, but the treated mice lived 10 days longer than untreated controls, surviving to an average of 139 days. This may seem a short reprieve, but for mSOD1 mice it was comparable to results obtained with other treatments, such as SOD1 antisense therapy (see Jul 2006 news story).

Koval and Miller are now investigating precisely how blocking miR-155 increases lifespan. The immune system’s role in the disease has proved to be complex, with both positive and negative effects (see Sep 2009 news story; Oct 2008 news story; Henkel et al., 2009). Koval speculated that the treatment dampens inflammatory processes that would otherwise exacerbate the disease. “It is presumably just a way of treating inflammation in the nervous system,” agreed Nelson. Therefore, the treatment would be unlikely to halt disease in people but might slow it down, Miller said. While researchers cannot directly correlate life extension in mice to that in humans, Miller hopes that an anti-miR-155 therapeutic would offer more than the extra few months people get from taking riluzole, currently the only approved treatment for ALS.

The Miller lab and Regulus are not headed for the clinic just yet. Toxicology work remains, and Koval needs to determine whether peripheral or CNS treatment, or both, explains the benefits. A peripheral treatment would be more convenient in the clinic, though Koval noted that researchers are making excellent progress with intrathecal delivery of antisense treatments directly to the CNS (see Mar 2011 news story; Jan 2013 news story).—Amber Dance

The authors of this interesting report have nicely demonstrated a new method of inhibiting micro RNAs (miRNAs) in vivo in a mouse model of ALS. Essentially, they have utilized oligonucleotides as miRNA inhibitors. By targeting one such miRNA, miRNA-155, they demonstrate improvement in their ALS mouse model, about a 10-day prolonged survival. From a neuroinflammation perspective, what I find most intriguing is that miRNA-155 is avidly taken up by microglia and astrocytes. While the authors do not further investigate a putative mechanism to account for this, it would be interesting to determine if an active process is at work here (e.g., fluid-phase pinocytosis) or whether some form of glial-neuronal interaction is taking place. Nonetheless, this work raises our awareness of the therapeutic potential of blocking miRNAs for neurodegenerative disease.…More

View all comments by Terrence TownPart one of a two-part story. Read part two here.

Neurodegenerative disease researchers have caught on that glia do more than supply energy to neurons or respond to emergencies such as amyloid accumulation or tissue damage. At the Society for Neuroscience (SfN) annual meeting, which drew nearly 25,000 scientists to San Diego November 9–14, researchers reported new data on the fundamental roles played by glial cells in forming and refining neural circuits. As the brain ages, those functions seem to get creaky, raising the possibility that keeping glial cells young and fit could protect against neurodegeneration. Other scientists outlined new approaches to promote a kind of glial cell activation that might help mice tackle Alzheimer’s-like pathology in the brain (see part two of this series).

Won-suk Chung, a postdoc in in Ben Barres' lab at Stanford School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California, studies astrocytes—the most common glial cell in the brain. Earlier work in the lab had revealed that the star-shaped cells express high levels of phagocytic receptors. Given that an individual astrocyte can touch thousands of synapses, Chung and colleagues wondered if astrocyte phagocytosis contributes to synaptic turnover. As described on their poster—and reported 24 November in Nature—they first examined neuronal-glial interactions in mice less than a week old. At this young age, retinal ganglion cells shed synapses as a normal part of visual system development. Using confocal microscopy, the researchers saw astrocytes engulfing axon terminals and synapses on these retinal cells. They saw the same with array tomography, a newer technique that allows quantitative, high-resolution imaging of serial tissue sections (see Micheva and Smith, 2007).

To test whether astrocyte phagocytosis is responsible for this synaptic pruning, Chung turned to mice lacking multiple EGF-like-domains 10 (MEGF10) and C-mer proto-oncogene tyrosine kinase (MERTK), two phagocytic receptors that are highly expressed in astrocytes (see Jan 2008 news story). Unlike wild-type cells, astrocytes in the MEGF10- and MERTK-deficient mice ingested no synaptic components and the visual system of these animals failed to mature, suggesting that phagocytosis of synapses contributes to development of the retina.

The wild-type astrocytes phagocytosed synapses in 1- and 4-month-old mice, as well, indicating that they prune synapses into adulthood. Based on preliminary data in older mice, however, Barres suspects the rate by which astrocytes eat synapses slows with age, leading to accrual of senescent synapses that would normally get recycled. If this in fact occurs, Barres said, it would explain the dramatic rise in complement component C1q detected at synapses in the brains of wild-type mice and people during normal aging (see Stephan et al., 2013). C1q is a lectin-like protein that binds apoptotic cells. “We assume that it binds senescent synapses in the aging brain,” Barres said. He plans to examine AD mouse models to see if their astrocytes engulf synapses poorly relative to wild-type animals. Prior work suggested complement helps rid plaques in AD mice (see Jun 2008 news story), though perhaps at the expense of cognition (Aug 2013 news story).

Marie-Ève Tremblayof Laval University, Quebec City, has addressed similar questions in her studies of how microglia interact with synapses. Using two-photon imaging, electron microscopy, and array tomography, she and others have reported that microglia cozy up to synapses and then chew them up in the brains of early postnatal and adolescent wild-type mice (see Nov 2010 news story; Schafer et al., 2012). However, in older mice, which lose cortical sensory neurons during age-related vision and hearing loss, Tremblay found that microglia are misshapen and clump together instead of spreading evenly throughout the brain as they do in younger animals (Tremblay et al., 2012). The findings agree with another two-photon imaging study that showed aging microglia phagocytosing more slowly and responding to tissue injury poorly compared to microglia in young mice (see Hefendehl et al., 2013), Tremblay said.

What about in mice modeling Alzheimer’s disease (AD)? Something similar seems to happen, Tremblay said. When her team examined brains of 6-month-old APP/PS1 mice with extensive plaque deposition, they saw that phagocytic capacity was down—APP/PS1 microglia interacted with synapses less and engulfed them only half as often as microglia from age-matched wild-type littermates (see image below). Comparing microglia from the transgenic mice to aged wild-type microglia, “what is similar is that microglia are impaired in their ability to phagocytose,” she said. “However, in wild-type animals you don’t see the problem until 20 months of age, whereas in APP/PS1 mice it appears at six months.”

Microglia (purple) in the hippocampus of wild-type mice chomp synapses (uncolored inclusions) heartily (left image), microglia from age-matched APP/PS1 mice much less so (right image). Image courtesy of Marie-Ève Tremblay.

The findings suggest to Tremblay that microglia might contribute to AD by phagocytosing too little rather than too much. Consistent with this notion, a recent study found that cultured microglia from AD mice were slower than wild-type microglia at phagocytosing fluorescent beads. The most dysfunctional microglia came from brain areas laden with Aβ, and relieving plaque load with anti-Ab antibodies restored the glial cells’ phagocytic capacity (Krabbe et al., 2013).

Other researchers at the meeting asked about data on human microglia. Tremblay said it is hard to find human tissue samples of sufficient quality for this type of analysis. She told Alzforum her team plans to collaborate with Naguib Mechawar of the Douglas-Bell Canada Brain Bank in Montreal to analyze human AD brain for phagocytic defects.

Two-photon imaging data on an SfN poster by Jean-Philippe Michaud and Serge Rivest of Laval University support the idea that innate immune cells become sluggish with age. The researchers analyzed APP/PS1 mice whose monocytes express green fluorescent protein. Imaging through a 1-mm cortical window each week from 4 to 9 months of age, the researchers watched GFP-labeled monocytes clearing Aβ out of veins that permeate the cerebral cortex (see image below).

Live imaging by two-photon microscopy shows monocytes (green) clearing Aβ (red) from veins (grey) in the cerebral cortex of transgenic mice modeling AD. Image courtesy of Paul Préfontaine and Jean-Philippe Michaud.

In 4-month-old AD mice with normal cognition despite accumulating plaques, “there seemed to be a natural defense mechanism where monocytes were able to clear vascular Aβ,” Rivest told Alzforum. However, by 9 nine months of age, this clearance was slowing down. The findings were published in the November 14 Cell Reports. In the future, the researchers hope to identify the molecular mechanisms that enable monocytes to home to vascular amyloid. Transcriptional profiling of monocytes from AD patients at different disease stages may help with this goal, Rivest said (see also part two).

However, disease can also correlate with overactive microglia. In a recent analysis of mice modeling human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurocognitive disorder, Tremblay and colleagues reported that cognitively impaired animals have overly phagocytic microglia, compared with wild-type littermates. A small-molecule phagocytosis inhibitor slowed dendritic spine loss in the disease mice; in vitro, it protected neurons against phagocytosis by microglia from these animals (see Marker et al., 2013).

Besides chewing things up—whether synapses, amyloid or other debris—activated microglia also release trophic factors that help build connections. At SfN, two-photon imaging data on a poster by Akiko Miyamoto and Junichi Nabekura of the National Institute for Physiological Sciences, Okazaki, Japan, showed that microglia are required for dendritic spines to form in the somatosensory cortex of early postnatal mice. Taken together, the data from the Canadian and Japanese groups suggests that microglia not only break down synapses but also help make new ones, adding synapse formation to the list of potential mechanisms that go awry in aging and AD.—Esther Landhuis

No Available Comments

This concludes a two-part story. Read part one here.

As researchers flesh out connections between the brain and the immune system, they are beginning to understand the role microglia play in disease. Prior research had blamed overzealous microglia for spewing inflammatory molecules that damage brain tissue, but recent studies suggest that AD may progress more quickly when these brain-resident phagocytes become sluggish and less responsive as they age (see part one of the series). Both scenarios may be true. At the Society for Neuroscience’s annual meeting, held November 9–14 in San Diego, several presentations focused on strategies to reinvigorate the brain’s innate immune cells. Researchers also presented approaches that harness innate immune pathways to reduce brain Aβ while toning down potentially harmful inflammatory responses. The new data raise hopes of capitalizing on beneficial glial cell responses, but don’t yet fully answer the question of exactly what those are.

The idea that innate immune activation might help in AD found early support in reports that blood-derived macrophages cleared brain Aβ in mouse models of AD. In 2008, researchers led by Terrence Town, now at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, reduced AD-like pathology in Tg2576 mice by crossing them to a transgenic strain whose macrophages lack anti-inflammatory TGFβ signaling (Jun 2008 news story). At SfN, Tara Weitz, a postdoc in Town’s lab, reported on a pharmacological version of the TGFβ-blocking strategy.

Weitz showed that the commercially available TGFβ inhibitor SB-505124 prompted primary mouse macrophages to chew up Aβ in cell culture. When she treated 14-month-old Tg2576 mice with a four-month regimen of biweekly intraperitoneal injections, the inhibitor slowed further amyloidosis in these already plaque-burdened animals. Moreover, activated, i.e., CD45-positive, peripheral macrophages infiltrated blood vessels in the cingulate cortex, the hippocampus, and the entorhinal cortex—regions of the brain where Aβ accumulates in people.

However, when Weitz and colleagues administered the inhibitor to 16-month-old transgenic AD rats, which also have a high amyloid burden (Cohen et al., 2013), plaque load hardly budged. Though disappointing, the results “confirmed our hypothesis that the rat may be a more stringent AD model that is harder to treat,” Weitz told attendees (see Aug 2010 conference story). Many treatment strategies that appear to cure mice of AD pathology have failed in human clinical trials (e.g., Aug 2010 news story; Dec 2009 news story).

The researchers are getting more promising results loading the inhibitor into nanoparticles developed by Tarek Fahmy, a medicinal chemist at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. In addition to carrying the TGFβ inhibitor, these 100- to 200-nm-wide particles carry the green dye Coumarin-6 for easy tracking. In cell cultures, the nanoparticles readily entered wild-type mouse macrophages, lingering in the cells about a week. “The macrophages ‘see’ the nanoparticles as trash, and voraciously gobble them up,” Town said. “It’s an elegant physiologic system requiring no surface labeling or targeting.”

The researchers tested the SB-505124-laden nanoparticles in 8-month-old AD rats, which had moderate amyloid load. When the particles were given weekly as a footpad injection, for six months, peripheral macrophages took them up. The macrophages then homed in on amyloid-laden cortical and hippocampal areas, the researchers found. Compared with control AD rats treated with drug-free nanoparticles, treated animals had fewer plaques and more activated macrophages as judged by CD11b expression.

Peripheral macrophages (red) devour nanoparticles (green) loaded with TGF inhibitor. Image courtesy of Tara Weitz.

At this point, it is unclear if the nanoparticles are more effective than the naked inhibitor, or whether starting injections at a much younger age made a difference, Weitz said. In addition to looking at behavioral readouts in the treated cohort, her team plans to administer SB-505124 nanoparticles to younger rats in a prevention paradigm.

The Town lab also tests other strategies to activate microglia. The researchers have bred PSAPP double-transgenic mice onto an interleukin (IL)-10-deficient background. Because IL-10 quells inflammation, “We’re essentially releasing brakes on innate immunity,” Town said. As reported earlier this year at a conference in Bonn, Germany, the IL-10-negative animals activate more microglia and accumulate less amyloid than PSAPP mice (see Mar 2013 conference story). At SfN, Marie-Victoire Guillot-Sestier of the Town lab showed that the IL-10-deficient PSAPP mice outperform controls in cognitive tests, steering clear of open fields and more readily recognizing novel objects. Without IL-10, the mice maintain better synapses, as measured by synaptophysin levels. The Town lab has a similar IRAK-M (IL-1 receptor-associated kinase M)-deficient PSAPP strain; synapse and cognitive data on that is forthcoming, Town said.

Paramita Chakrabarty and Todd Golde of the University of Florida, Gainesville, have data that complement Town’s work. Rather than blocking IL-10, these researchers used adeno-associated viral vectors to overexpress this cytokine in the brains of two AD mouse strains. TgCRND8 mice received the transgene injection at birth and Tg2576 mice at 8 months of age, when amyloidosis is well underway. Relative to vehicle controls, IL-10-overexpressing TgCRND8 mice racked up more plaques, performed poorly on fear-conditioning tests, and their microglia appeared less phagocytic, Golde said. The IL-10-overexpressing Tg2576 mice also had higher plaque burden compared to regular Tg2576.

Furthermore, Chakrabarty presented a strategy that clears brain Aß in TgCRND8 mice while dampening microglial activity. The researchers enlisted toll-like receptors (TLRs); these are surface receptors on immune cells that recognize proteins typically found on microbes. TLRs also bind Aß, and microglia from TLR4 knockout mice cannot phagocytose the peptide (Sep 2009 news story on Reed-Geaghan et al., 2009; see Boutajangout and Wisniewski, 2013 review).

To curb cerebral amyloidosis, Chakrabarty and colleagues engineered soluble forms of TLRs 2, 4, 5, and 6 that contain the receptors' extracellular Aß-binding region but lack their cytoplasmic signaling domains. The truncated molecules behave as decoys, neutralizing Aß without stimulating unwanted inflammatory responses. Widely used anti-inflammatory drugs function that way, for example the tumor necrosis factor decoy receptor etanercept. TgCRND8 mice that had received injections of truncated soluble TLR4 (sTLR4) or soluble TLR5 (sTLR5) at birth grew up accumulating fewer plaques and less soluble Aß in the brain. In addition, fewer glial cells surrounded plaques in the brains of sTLR4- and sTLR5-expressing mice, and those that did had blunted responses as judged by expression of the glial activation marker GFAP.

In culture, the decoy receptors blocked the toxic effects of aggregated Aß42 and α-synuclein, and ELISAs confirmed they did so by binding the protein aggregates, Chakrabarty reported. In future experiments, the researchers hope to determine if the soluble TLRs can reach the brain if given peripherally and prevent cognitive deficits. In addition, Golde’s group is testing whether the approach could help AD mice with amyloidosis already underway, and if it can alleviate pathology and behavioral deficits in stroke models and transgenic mice overexpressing tau or α-synuclein.

Active, Idle, or Simply Different?

While the sTLR approach seems to suggest otherwise, broadly speaking “there is an emerging concept that microglia in amyloidosis mouse models are less active than they should be,” David Morgan of the University of South Florida, Tampa, told Alzforum. Their suppressed state “is somehow induced by amyloid deposition, and relieving the suppression enables circulating monocytes to go into the brain and clear out the amyloid,” Morgan said. However, he cautioned that activating microglia may not be a viable treatment for AD as it worsens tau pathology in some mouse studies (Ghosh et al., 2013; Oct 2010 news story; see also Lee et al., 2013 review).

Furthermore, it is still hard to figure out which immune cells to activate, and how. Researchers had looked to distinguish harmful and helpful microglial subtypes, dubbed M1 and M2, based on their expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, but now some scientists consider these designations inadequate (see Mar 2013 conference story). “I think we need to drill down further to identify the specific protein markers that go up under conditions where we’re clearing amyloid from the brain,” Morgan said.

As outlined on an SfN poster by Kevin Doty, who studies bioinformatics in the Town lab, scientists are starting to make inroads in this direction. Hypothesizing that targeting specific immune mediators is better than generally dialing inflammation up or down, Doty tried to establish why PSAPP/IL-10-negative mice accumulate less Aß. He profiled transcription in whole-brain tissue with RNA sequencing and network analysis. He found that the mice downregulated a handful of genes involved in innate immune regulation. That list includes the microglial receptor TREM2, which was recently identified as an AD risk gene (Nov 2012 news story). “While the link between the rare TREM2 variant and AD risk remains poorly understood, one possible explanation for Doty’s findings is that TREM2 inhibits Aß phagocytosis by microglia,” said Town. The work also suggests that IL-10 is involved in TREM2 regulation “The goal is to identify a ‘fingerprint’ for beneficial innate immune activation to aim for with Alzheimer’s immunotherapies,” Town told Alzforum.

Applying a similar strategy on purified microglia from wild-type mice, Joseph El Khoury of Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, and colleagues identified 100 genes that are differentially expressed in aging microglia. TREM2 made that list, too—as did another AD risk gene, CD33, and DAP12, an adaptor protein that mediates TREM2 signaling but has no known genetic connection to AD yet. El Khoury reported some of this data at the recent Venusberg meeting (see Mar 2013 conference story), and in full in an October 27 Nature Neuroscience paper (Hickman et al., 2013). “These studies are telling us there are many different types of activated microglia,” Town said. While El Khoury is finding that microglia change their activation profile with age, “we are finding that they change in the context of AD pathology.”

Other scientists at SfN presented research aimed at identifying microglial-specific markers. Mariko Bennett of Ben Barres’ lab at Stanford School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California, isolated RNA out of microglial-enriched, CD45-positive pools of cells from healthy mice. They identified transmembrane protein 119 (TMEM119) as a novel microglia-specific marker. About 93 percent of myeloid cells in the brain and spinal cord express TMEM119 RNA, and the protein is highly restricted to microglia.—Esther Landhuis

No Available Comments

Though typically considered an axonal protein in neurons, tau is found in dendrites in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative disorders. More recent studies have reported tau in dendrites under normal physiological conditions as well, and researchers are beginning to tease out its role there in both health and disease. At the Society for Neuroscience annual meeting held November 9–14 in San Diego, scientists nailed dendrites as the source of the tau-dependent neuronal hyperexcitability in AD mice and proposed a role for the microtubule binding protein in postsynaptic signaling.

Back when he was a postdoc in Lennart Mucke’s lab at the Gladstone Institute for Neurological Disease in San Francisco, Erik Roberson found that crossing J20 APP transgenic mice with tau knockouts reduced spontaneous seizures (Sep 2007 news story; May 2007 news story). He then found that knocking out tau not only normalized network activity in other mouse models of AD but also in mice modeling epilepsy (Roberson et al., 2011; see also May 2011 conference story; Jan 2013 news story). In adult mice susceptible to seizures, suppressing tau also suppressed the convulsion (DeVos et al., 2013).

At SfN, Roberson, who is now at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, presented his lab’s latest work delving into mechanisms behind this protection. The scientists wondered how dendritic tau regulates neuronal excitability in AD mice.

To address that question, the researchers collaborated with Ben Throesch in Dax Hoffman’s lab at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland. This is one of the few research groups with expertise in dendritic patch-clamps (Davie et al., 2006). Analyzing the J20 mice, the scientists found that their dendrites spiked more robustly than non-transgenic littermates. This was evidenced by higher-amplitude action potentials transmitted away from the soma toward the dendrites. These back-propagating pulses are a standard measure of dendritic excitability. No such changes were detected in the rest of the cell. This “localizes the neuronal hyperexcitability we see at the network level to dendrites,” Roberson suggested.

To probe the molecular basis for the defect, Alicia Hall in Roberson's lab examined the three primary channels that regulate excitability in dendrites. In J20 mice, the CA1 and dentate gyrus expressed lower levels of the Kv4.2 potassium channel, relative to non-transgenic littermates, whereas levels of the other two (HCN1 and HCN2) remained unchanged, Roberson reported. The potassium current Kv4.2 carries is hyperpolarizing, and less Kv4.2 is known to increase dendritic excitability. How dendritic tau might reduce expression of the potassium channel remains a mystery.

Loss of Kv4.2 affects behavior, as well. When the researchers mated the mildly amyloidogenic J9 strain with Kv4.2 knockout mice (Guo et al., 2005), the crosses performed worse in short-term spatial memory tasks that J9 mice typically handle with ease, Roberson said. In tau-deficient APP mice, dendritic excitability looked normal.

At SfN, Lars Ittner of the University of Sydney proposed another role for tau, that is, regulation of postsynaptic signaling through the kinase ERK. This line of work began when the scientists noticed that tau knockout mice do not turn on expression of the immediate early genes (IEG) fos, arc, and JunB in response to pentylenetetrazol (PTZ), a seizure-inducing compound. Checking upstream of IEGs, the researchers found no ERK phosphorylation, and even further upstream, only weakly active synaptic Ras in brain slices from these tau-deficient mice. The wan activity of Ras was not due to its concentration, but rather due to an excess of its inhibitor SynGAP1. This Ras-GTPase activating protein occupies synaptic complexes with postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95) and NMDA receptors. “Levels of this endogenous Ras inhibitor are massively increased in dendritic spines of tau knockout mice,” Ittner reported. This hints that something changes in the PSD-95 complex to allow more SynGAP1 to bind, and that then keeps Ras, and therefore ERK, turned off when NMDA receptors are activated, he suggested.

The work would suggest that tau keeps SynGAP1 away from the PSD-95 complex. Ittner and colleagues are still trying to figure out how that happens. In the meantime, they and other researchers are looking to develop therapeutics that mimic the benefits of less tau by targeting factors that interact with it. One such candidate is the Src kinase fyn. Several years ago, researchers led by Ittner and Jürgen Götz, who is now at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, reported that tau targets fyn to the N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor, where it phosphorylates the 2b subunit. This strengthens the receptor’s interaction with PSD-95 and promotes Aβ-induced excitotoxicity at the synapse (Jul 2010 conference story on Ittner et al., 2010). Roberson and colleagues found that fyn overexpression exacerbates AD-related seizures and cognitive impairment in amyloidogenic mice, and that engineering fyn/APP mice with a tau-deficient background mitigated these problems.

The Roberson lab presented several posters detailing their efforts to target tau-fyn interactions. In a high-throughput screen of 90,000 small molecules, Nick Cochran and colleagues found several dozen that blocked tau-fyn interaction. They plan to take candidates that look promising into cells and tweak them to make them more potent and specific.

In related work, Pauleatha Diggs in the lab explored the role of phosphorylation in tau-fyn interactions. Dendritic tau becomes hyperphosphorylated at particular sites, and phosphorylation by microtubule-affinity-regulating kinase (MARK) correlates with localization of tau to dendrites. When the researchers pseudophosphorylated four MARK sites in tau’s microtubule-binding domains, the tau bound more tightly with fyn than did wild-type tau. These findings suggest that tau and fyn form a tight complex in dendrites. This would strengthen the rationale for blocking the tau-fyn association as a therapeutic approach.—Esther Landhuis

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.