Genetic Wild West: 23andMe Raw Data Contains 75 Alzheimer’s Mutations

Quick Links

The spit tube arrives in the mail in a pretty box, stamped with the cheery message “Welcome to You.” The journey into your genome begins a few weeks later, with an email inviting you, a 23andMe customer, to explore your DNA. You’ll learn fun facts about your ancestry, your Neanderthal vestiges, and whether you are likely to turn beet red from a single cocktail. But if you want, the company will also disclose genetic health risks, and this is where things turn serious. Approved in April 2017 by the FDA, 23andMe’s health reports estimate genetic risk for four diseases so far, including Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s—the latter based solely on carriage of the ApoE4 allele. Customers also learn if they are unwitting carriers of any of 42 recessive alleles that pose no threat to them, but could harm their children. Importantly, with a few more clicks you can open Pandora’s box, filled to the brim with your genotype at some 600,000 single polymorphism (SNP) positions. You can download this nondescript list of A, C, T, and G combinations to your computer. At this point, you are on your own. 23andMe warns that this data isn’t validated. Some SNPs have spurious associations in the published literature. Others could pack quite a blow. The 23andMe chip reveals your genotype at 75 of the dominantly inherited mutations known to cause Alzheimer’s disease. Once that data is on your computer, can you resist taking a peek?

The implications are exciting, as unfettered access to one’s own genetic data holds great opportunities: In the case of ApoE4, it may motivate carriers to join an AD prevention trial or adopt a healthier lifestyle. People who discover in their raw data that they carry an autosomal-dominant AD (ADAD) mutation may find their way to the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network (DIAN). However, to the chagrin of AD researchers, 23andMe has not agreed to refer carriers of these mutations toward such clinical studies.

The implications are also unnerving. The company told Alzforum that 2 million people have ordered the 23andMe kit since 2007, but declined to say how many found out their ApoE status or accessed their raw data. Even so, the overall growth of the direct-to-consumer (DTC) testing industry makes it likely that, before long, millions of people will grapple with the meaning of the complex, unwieldy, and massive data set that is their genome. Health care providers and genetic counselors—trained to guide people toward making informed decisions about whether to order genotyping—are increasingly being asked to pick up the pieces afterward. This amounts to crisis counseling for distraught consumers caught off-guard by their results. Others may not tell a soul, perhaps fearing discrimination by employers or insurers based on their genes. The company’s efforts to link customers to genetic counselors to help them understand surprises lurking in the raw data are seen as insufficient by some.

In general, the rise of direct-to-consumer genetic testing, a field 23andMe pioneered, raises scientific, ethical, and social issues that must be addressed, said Carlos Cruchaga of Washington University in St. Louis. “Clearly this is happening,” he told Alzforum. “Human genetics is moving very quickly. It’s easy to obtain the data, but understanding how to deal with it has always been a challenge.” Researchers sharply disagree on the ethics of selling raw genetic data to the general public.

After Early Stumble, DTC Genetic Testing Is Off to the Races

23andMe began offering its direct-to-consumer genetic testing services more than a decade ago, at one time providing its customers with genetic risk assessments for 254 diseases in addition to information about their ancestry and other physical traits. That changed in the United States in 2013, when the FDA shut down the company’s genetic risk component until it could show its tests and interpretations were valid (see Feb 2014 news). In April 2017, the FDA authorized the company to market so-called genetic health risk reports for 10 diseases, each validated for technical reproducibility and clinical relevance based on the scientific literature. In addition to AD and PD, the approved risk reports interpret variants associated with α-1 antitrypsin deficiency and hereditary thrombophilia. Reports for Gaucher disease type 1, celiac disease, early onset primary dystonia, factor XI deficiency, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, and hereditary hematochromatosis have also been approved but are not available yet. Carriage of the ApoE4 allele is used to assess a customer’s AD risk, while the G2019S mutation in LRRK2 and the N370S mutation in GBA are used for PD. Nowadays, customers can choose between two products: the cheaper ancestry-only results, or ancestry plus health reports.

As part of its pre-authorization work with the FDA, 23andMe had to conduct a study to show that consumers could understand their results and what they meant. The company agreed to present customers with warnings and limitations prior to unlocking their genetic health risk reports. This includes statements that genetic risk is but one component of overall risk, that the tests do not diagnose a disease, and that the results may upset some people. The company also suggests some clients may benefit from genetic counseling—either before or after receiving test results—and directs them to the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) to search for a counselor.

Susan Hahn, a NSGC member who specializes in AD, told Alzforum that direct-to-consumer testing has shifted the workload of counselors toward post-counseling, rather than pre-counseling. Most counselors work in partnership with health care providers, and help clients decide ahead of time if genetic testing is the right choice for them. “A genetic counselor may raise the difficult questions you didn’t think to ask yourself,” she said. With the rise of DTC testing, Hahn said counselors are increasingly seeing clients only after the test results are in. “At that point, you’re often just doing damage control,” she said, referring to clients who took the tests without fully considering the consequences.

Processing unexpected genotype information can be difficult. Jamie Tyrone, 57, of San Diego found out she carried two copies of the ApoE4 allele as a participant in a research study exploring attitudes about genetic risk. She had joined the study to know more about the genetic underpinnings of multiple sclerosis, but was unaware she would find out her ApoE genotype. She was offered no genetic counseling as part of the study, she told Alzforum. “Had I seen a counselor, I would have decided not to participate,” she said. Tyrone’s father suffered from AD, so she knew the gravity of the disease. The result pitched her into a dark hole, she said, and she was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, a condition she claimed cost $40,000 in counseling. Ironically, the study Tyrone participated in concluded that most volunteers did not suffer clinically significant levels of anxiety or distress (Boeldt et al., 2015).

Nowadays, Tyrone participates in a longitudinal study sponsored by the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute in Phoenix, which aims to chart the preclinical course of AD. When she turns 60, she hopes to qualify for a clinical trial. “The opportunity to participate in research is the only benefit I’ve received from learning about my ApoE genotype,” Tyrone told Alzforum.

23andMe does warn its users about the implications of learning about ApoE4. Still, Tyrone told Alzforum that she considers these warnings inadequate to prepare people for the consequences.

Other ApoE4 carriers see it differently. Julie Gregory, 55, of Long Beach, Indiana, found out in 2012 that she carried two copies of ApoE4 using 23andMe. At that time, the company had yet to offer genetic health risk reports that explained the results. Shaken and confused, Gregory started commiserating with hundreds of other carriers on 23andMe’s customer forums. Those interactions motivated her to form the website ApoE4.Info, where ApoE4 carriers support each other and discuss the latest research. “Although I was initially traumatized, knowing my status has been a good thing for me,” she said. “Knowledge is power.”

Gregory told Alzforum that while genetic pre-counseling would have been helpful, she doubts most people use it. “It’s great advice, but I’ve never seen anyone follow it,” she said. More important is that people have a place to turn after finding out their results, and that they feel motivated to make lifestyle changes to counter their genetic risk, she said. Gregory added that while she knows people who suffered severe psychological harm after learning their genotype, including PTSD, they tend to be the exception.

Gregory’s observation has a basis in research. In a recent study, only 4 percent of DTC genetic testing customers sought counseling (Koeller et al., 2017). Scott Roberts of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor headed the study, which surveyed more than 1,000 customers of 23andMe and Pathway Genomics, another genetic testing company, in 2012, before 23andMe ran afoul of the FDA. The few participants who did use counseling tended to have had prior experience with genetic counselors, were highly educated, more affluent, and younger. Far more people shared their genetic testing information with primary care providers than with genetic counselors. This deference to physicians could be a case of “first-stop shopping,” Roberts told Alzforum, or a consequence of the dearth of available genetic counselors. He added that many genetic counselors have long waiting lists; they also tend to give DTC customers low priority because they consider at-home tests less urgent than those ordered by a doctor.

Does 23andMe point its customers toward clinical studies they could join? Not in Alzheimer’s disease. As part of its genetic health risk reports, the company shares general research information with its customers, including risk statistics for each variant, other non-genetic risk factors (such as cardiovascular disease, education, and lifestyle), and data supporting the potential benefits of exercise and diet. However, the company does not point them toward specific studies geared to their genotype.

For ApoE4 homozygotes, an obvious choice would be the Generation program by Novartis and Banner. This set of two secondary prevention/early intervention trials is evaluating a BACE inhibitor and an Aβ vaccine from Novartis in asymptomatic ApoE4 homozygotes and heterozygotes (Sep 2016 conference news). These trials are ramping up, seeking a total of 3,340 participants. Based on the allele frequency of ApoE4, more than 100,000 people will have to be screened genetically to fill those trials alone. Researchers universally agree that recruiting asymptomatic, at-risk participants who are willing to learn their ApoE status represents a significant challenge for trial sponsors and participating sites in academia and industry.

23andMe could help with this challenge. After all, presumably many thousands of people have learned their ApoE genotype through the company. According to Jessica Langbaum at Banner, the institute has tried, but has not been able to come to such an agreement with 23andMe. Banner, Novartis, and 23andMe all declined to discuss the issue further with Alzforum, citing ongoing negotiations or legal concerns. In the past, 23andMe has monetized its genetic data, receiving $60 million from Genentech for access to its Parkinson’s data (Jan 2015 news). For now, absent a referral partnership with 23andMe, Langbaum told Alzforum that Banner is stepping up its own efforts to raise awareness about the Generation program, in hopes of catching the attention of the growing number of ApoE4 carriers who have learned their genotype.

Langbaum noted that several former 23andMe customers have found and joined the Generation program. Even though they entered the study already aware of their genetic status, these volunteers undergo the same extensive counseling as other participants in the trial, and then get genotyped again to confirm their status. Prior to joining a Generation trial, many of these participants had already done extensive private research about ApoE; alas, many of them only got a taste of one-on-one genetic counseling upon joining the study, said Langbaum. “For most people, this is their first chance to ask someone questions,” she said.

Your Data in the Raw: A Trip Down the Genomic Rabbit Hole?

If the impact of learning your ApoE genotype seems unpredictable, imagine opening a data file containing 600,000 genotypes. 23andMe gives customers access to their personal file, with the stipulation that variants other than the select few included in the genetic health risk reports are not validated for accuracy. The company tells customers that the raw data is only suitable for “research, educational, and informational use, and not for medical, diagnostic, or other use.” Still, inquiring minds may want to know.

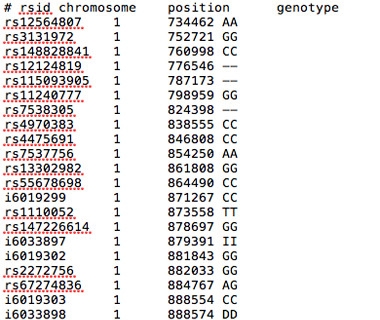

Data in the Raw.

A text file of raw data from 23andMe lists the rsid number, chromosome position, and genotype associated with each of more than 600,000 polymorphisms.

Customers can browse their raw genotype data—either by chromosome, gene, or SNP—on 23andMe’s secure website. They can also download it, and upload it to a third-party service for interpretation. For example, for $5 and with a simple click on a bright-green button on its website, Promethease, currently the most popular of these genome-interpretation services, will upload anyone’s 23andMe data. Less than 15 minutes later, the customer can browse their SNPs within Promethease. This site curates information about the potential meaning of DNA variations from SNPedia. For its part, SNPedia derives its data from a variety of sources, including the scientific literature, the NIH-supported database ClinVar, and even the Alzforum mutations database. The current 23andMe genotyping chip contains about 20,000 of the roughly 100,000 SNPs curated by SNPedia, according to SNPedia and Promethease co-founder Greg Lennon.

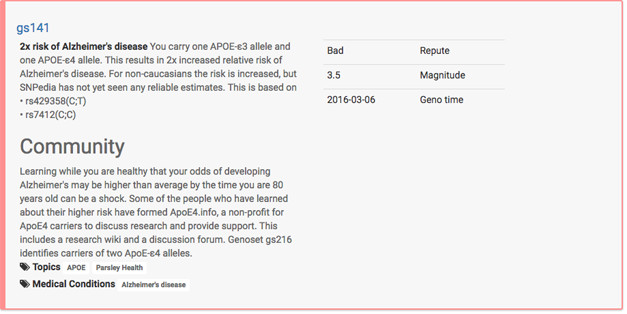

Perhaps most importantly, a 23andMe/Promethease customer can type in any of the genes known to harbor ADAD mutations—PSEN1, PSEN2, or APP—and voila, a list of potentially pathogenic mutations pops up, along with your predicted genotype, and whether that genotype is “good” or “bad,” and how bad on a scale of one to 10 (see example below).

Dominant Data. One of many ADAD mutations listed in Promethease, found by uploading a 23andMe raw data file and searching for PSEN1. “Magnitude” refers to the size of the variant’s effect. This sample person carries the T allele; if he or she carried the G allele in this location, “Repute” would indicate “Bad,” and “Magnitude” would likely indicate the maximum assigned for the pathogenic variant, in this case 7.

According to an analysis conducted by Cruchaga, the custom Illumina genotyping chip that 23andMe currently uses contains 75 familial AD mutations: 53 in PSEN1, nine in PSEN2, and 13 in APP. In addition, Alzforum found dozens of autosomal-dominant mutations for frontotemporal dementia (FTD) in the tau (MAPT), progranulin (GRN), and CHMP2B genes. A bevy of risk-associated SNPs are also represented, including many of the current top 10 GWAS hits listed for AD (see AlzGene), PD (PDGene), and ALS (ALSGene).

Outside of neurodegeneration, SNPs on the 23andMe chip have been linked to myriad other diseases or traits, including cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, addictive behavior, even lack of empathy. Other SNPs were included on the chip to derive ancestry information.

Customers who open their raw data file can find out their genotype at any of the 600,000 SNP positions contained on the chip, far beyond the 18 SNPs that are used for the genetic health risk reports that 23andMe shares with FDA approval. The raw data is available to all customers, even those who purchase the less expensive ancestry-only product that does not come with genetic health risk reports or carrier status, Wu told Alzforum. Therefore, if an ancestry-only customer carrying an ApoE4 allele were to upload his or her raw data to Promethease, they could see their ApoE genotype (see below). 23andMe is not the only DTC genetic testing company that shares raw data with its customers. For example, Ancestry.com customers can also riffle through their raw data, which contain myriad clinically relevant SNPs as well.

Ready or Not: ApoE4. A carrier uploading his or her data to Promethease would face this entry. gs141 designates the ApoE3/4 genotype. Carriers are referred to Julie Gregory’s ApoE.Info website for support.

Surprises in a person’s raw data raise questions about accuracy and once again highlight the importance of genetic counseling. Consider Summer Warner, a Midwestern U.S. woman in her early 20s. Warner was just curious about her ancestry, but got blindsided by an apparent increased risk for developing a deadly neurodegenerative disease. She received her 23andMe results back in 2010. Uploading her raw data to Promethease a few years later, Warner discovered that she had variants associated with the C9ORF72 hexanucleotide expansion that can cause amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or frontotemporal dementia. Terrified, she followed a link from 23andMe’s website to Informed DNA, a genetic counseling service. The company informed Warner that they would not discuss the result with her, Warner told Alzforum. Seeking advice, she reached out to 23andMe,which assured her that Informed DNA would indeed talk with her. She tried again, and received no response. When she reached out to genetic counselors at Washington University in St. Louis, the closest major city, they told her they would not discuss raw data from 23andMe, as they were not validated to clinical standards.

Nevertheless, Warner persisted, and ultimately found her way to Chris Shaw of King’s College London, a geneticist and co-author on the ALS research study mentioning her variant. Shaw relieved Warner’s worries over email. “From our analysis it appeared that the SNP data did not increase her risk of carrying the C9ORF72 disease allele,” Shaw told Alzforum separately. “Her haplotype itself is very common in Europeans and is in no way a proxy for the expansion mutation.” Warner said that while this information assuaged her anxiety, it would have been preferable to speak with a genetic counselor. “Instead, I had to go this crazy route,” Warner said.

Shaw declined to comment about 23andMe directly. He told Alzforum that he considers it irresponsible to share this kind of raw genetic information with people without counseling. Shaw added that complex genetic data, and its relationship with disease risk, is often misunderstood or disagreed upon even among geneticists, counselors, and clinicians, let alone the average person. Even supposedly solid risk factors such as ApoE4 have varied effects in different populations, he said. “Misinformation about genetic data can generate a lot of fear,” he said.

The amount and quality of the data backing up the alleged phenotypic meaning behind a given genotype varies greatly; it evolves along with the progress of human genetics research overall.

Adam Boxer of the University of California, San Francisco, said he would approach 23andMe’s raw data with a hefty dose of caution. In particular, Boxer questioned the ethics of handing over information about causal mutations outside of a clinical context, without counseling, and using unvalidated data. Boxer heads the ARTFL consortium, which conducts longitudinal studies on FTD (Nov 2014 conference news). Among ARTFL’s participants are asymptomatic carriers of autosomal-dominant mutations in tau, progranulin, and C9ORF72, some of which can be found on the 23andMe genotyping chip. Boxer said ARTFL adheres to strict protocols for disclosing information about causal mutations to its participants. While he stopped short of suggesting that people not be allowed to access their raw data files, he suggested some sort of warning system or firewall be put in place to alert carriers of severe mutations that they may be about to view potentially alarming information.

Bradley Boeve of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, heads LEFFTDS, a subset of ARTFL that includes carriers of autosomal-dominant FTD mutations. Boeve told Alzforum that he would be “uncomfortable” with any DTC company offering testing for causal mutations. He cited the potential for psychological harm to people who learn the information in the wrong context. Echoing Shaw and Boxer, Boeve added that there are aspects of genetics that uninformed people would not understand without counseling, such as incomplete penetrance.

Some of the causal mutations genotyped on 23andMe’s chip—including most FTD mutations—require genetic know-how to find, as not all of them pop up readily via a third party like Promethease. Even so, in essence, 23andMe informally makes available hard-hitting genetic risk information far beyond the formal health reports sanctioned by the FDA.

Shirley Wu of 23andMe reiterated to Alzforum that the company does not recommend that its customers attempt to extract clinical information from the raw data, but added that they should be free to look through it. “We don’t want to be the gatekeepers of this information,” she said. “It is really the individual’s choice what they want to do with their data.”

According to Wu, the genetic counseling landscape is changing, as a growing cadre of counselors are beginning to specialize in the interpretation of direct-to-consumer genetic results. Brianne Kirkpatrick, owner of Watershed DNA in Crozet, Virginia, is such a counselor. She started her service after encountering anxious people in Warner’s situation, she told Alzforum. Kirkpatrick counsels people before and, more commonly nowadays, after they undergo direct-to-consumer genetic testing. She helps people interpret findings in their raw data files. Kirkpatrick told Alzforum that confusion and anxiety are common. For example, one recent client had a scare upon seeing the list of pathogenic Alzheimer’s mutations in Promethease, because she did not understand that she carried the normal, rather than pathogenic, variant of each one.

Kirkpatrick said she sometimes helps clients navigate the literature supporting disease- associated SNPs, making a point not to overinterpret weak or contradictory information. If a pathogenic mutation, such as an ADAD mutation, is reported, Kirkpatrick recommends that clients obtain a clinical-level genetic test to confirm it. She added that the disclaimers direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies use to caution clients against overinterpreting their raw data don’t work with most people. “Even with the disclaimer, people still believe the data is reliable,” Kirkpatrick said. “The disclaimers are not sufficient to educate the public.”

Case in point, Alzforum found several heart-stopping errors within a 23andMe raw data file obtained from a volunteer. Using rsid numbers associated with mutations in the AD and FTD Mutation Database, Alzforum found genotypes for 26 pathogenic progranulin mutations in the volunteer’s raw data file. According to the genotypes called by 23andMe, this person was homozygous for three separate dinucleotide deletions, each reported to cause FTD in an autosomal-dominant fashion. Homozygous progranulin mutations trigger the childhood lysosomal storage disease neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCL). However, this volunteer is a healthy adult with no family history of FTD or NCL.

Why the error? One possibility is that the mutations—which have been documented in the genetics literature in one to seven families each—are not actually pathogenic, or were mislabeled in the ADFTD mutation database. A more likely explanation in this case is that the volunteer’s genotypes were wrong, Jose Bras and Rita Guerreiro of University College London explained to Alzforum. Genotyping chips often interpret deletions and insertions incorrectly, they said. In fact, Bras and Guerreiro ran into this same issue with some progranulin mutations on the NeuroXChip—a genotyping chip for neurological disorders that they helped design. Bras said that Illumina, the company that manufactures both NeuroX and 23andMe’s custom chips, gives researchers an estimate of how likely a given mutation is to be called correctly. But in the end, the only way to know for sure is to try the chip out, they said. If it proves not to work for a given genotype, researchers know to ignore it. “Of course, unlike 23andMe, we are not giving this raw data to customers,” Bras said. The progranulin problem is a prime example of just how unvalidated the raw data can be.

People who have had their entire genomes sequenced—an undertaking that is becoming increasingly affordable—have run into similar mismatches between their genotypes and phenotypes. A recent study reported that 11 out of 50 people who had their genomes sequenced supposedly carried pathogenic variants for various disorders. However, only two of those people actually had outward signs of the disease (Vassy et al., 2017).

Given the validation the FDA required to approve the 10 genetic health risk reports 23andMe issues, how does the agency view the raw data? Nary a mention of the raw data file appears in FDA’s authorization letter to 23andMe. The letter does state, however, that the 23andMe personal genome service, which includes the approved genetic health risk reports, cannot be used for “assessing the presence of deterministic autosomal dominant variants.” In an email to Alzforum, the FDA wrote, “Excluded from this authorization are diagnostic tests that are often used as the sole basis for major treatment decisions. Tests providing diagnostic information would be a different intended use to the genetic health risk reports recently authorized by the FDA and require a separate FDA submission.”

Alberto Gutierrez, director of the FDA’s Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health, which approved 23andMe’s genetic health risk reports, told Alzforum that the agency regulates the interpretation of genetic data, not the data itself. “There is a very strong desire by some people to own what they think is their data,” Gutierrez told Alzforum, referring to the raw data files. “As long as 23andMe is not making medical claims about it, we’re allowing them to share it.” What about third-party companies, such as Promethease, that do offer data interpretation? Gutierrez said that the FDA is watching such companies closely, and plans to contact those that “cross the line,” although exactly what that means is unclear at the moment.

In a June 20 commentary about the FDA’s approval of genetic health risk reports published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, Julia Wynn and Wendy Chung from Columbia University in New York criticized the agency’s attempt to separate genetic information from medical claims. “To allow DTC genetic testing and not expect persons to use the information to inform medical decisions is disingenuous and irresponsible,” they wrote. “This ruling is confusing—in asymptomatic persons, the genetic test provides the only data to support the diagnosis of or increased risk for such conditions as Alzheimer or Parkinson disease, and could be the sole basis for a medical decision.”

Good examples of medically actionable information are the BRCA mutations known to drive risk for breast cancer, FDA spokesperson Tara Goodin told Alzforum, because carriers could seek preventive procedures such as a mastectomy. BRCA mutations are not included in the genetic health risk reports, though some are in the raw data file. But how about the 75 autosomal-dominant AD mutations lurking in the raw data? Goodin told Alzforum that as the data are not validated, nor interpreted by 23andMe, customers should not view them as diagnostic tests. If someone were to find they harbored such a mutation, the next step would be to confirm the result via clinical testing with a health care provider, she said.

Randall Bateman of Washington University in St. Louis partly agrees. However, he recommended that before seeing a doctor, people who discover one of these deterministic mutations in their 23andMe raw data first secure life and long-term care insurance, especially if they have a family history of AD. The reason is that, unlike workplace equality or access to medical insurance, access to life and long-term care insurance are not protected under the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA). Once a person has a validated clinical result on his or her medical record, he or she may be required to divulge it on insurance application forms. This issue has even come up for people who carry two copies of the ApoE4 allele (May 2017 New York Times article). After getting insurance, the next step would be to decide, with the guidance of a genetic counselor, whether to seek bona fide clinical testing for the mutation, Bateman said.

Bateman readily acknowledged that discovering a familial AD mutation in a raw data file could be disturbing. “Maybe you were just interested in finding out if you descended from Vikings, and then you find one of these mutations instead,” he said. However, he added that given the strong family history of autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease, the revelation would come as little surprise for most carriers of ADAD mutations. People who discover such a mutation in their raw data file can contact the DIAN study through the DIAN Expanded Registry, where they will be guided toward counseling if they wish. In fact, a few participants discovered DIAN after perusing their 23andMe raw data, though they did so without referral help from the company.

Just as 23andMe has no partnership with Banner or Novartis to direct ApoE4 homozygotes to the Generation trials program, it also does not point carriers of ADAD mutations to DIAN. 23andMe spokesperson Andy Kill told Alzforum that as of now, the company does not keep tabs on how many of its customers carry ADAD mutations. However, Bateman said that directing these carriers to the DIAN registry would align with the company’s mission of sharing useful information with its customers. Like the Generation program, DIAN is expanding; its trials unit DIAN-TU in particular needs more participants to gain statistical power for its prevention studies.

Given the serious implications of carrying an ADAD mutation, Bateman raised the bar, suggesting that direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies have a responsibility to share this information with willing customers. After all, a person who has ordered this product has expressed an interest in genetic information, and arguably deserves follow-up in instances where there are concrete actions he or she can take in the face of distressing risk, such as join a prevention drug study. Bateman proposed a notification process by which the testing company would ask both carriers and non-carriers whether they would want to be notified if they did harbor a serious mutation. For those who answer yes, the company could perform clinical testing to confirm the result, and cover the cost of genetic counseling. Boxer would like to see a similar effort to refer carriers to registries that feed research studies such as ARTFL.

“These companies could develop a process to enable individuals, in a safe and ethical way, to find information that may change their lives and the lives of their families,” Bateman said. “As holders of this information, DTC companies are in the position to make a difference. The question is, what kind of difference do they want to make?”

Besides 23andMe, another venue for recruitment to prevention trials would be genetic-interpretation companies such as Promethease. People who find out their genotype there could be directed to trials such as the Generation program (for ApoE4 carriers) or the DIAN registry (for ADAD mutation carriers). Of course, this pool would be limited to customers who took the step of analyzing their data via Promethease.

Lennon, the co-founder of SNPedia and Promethease, said his company is willing to direct mutation carriers to prevention studies. “We could do this automatically, and easily,” he told Alzforum. “But every foundation or nonprofit we’ve gone to has ultimately said no.” While he declined to name the organizations, he said that they were wary of referrals based on unvalidated data, or that they asked for too much exclusivity at the expense of other foundations.

Lennon told Alzforum that Promethease tries to give carriers of pathogenic variants medically useful information as available. One source is the evidence-based summaries developed by ClinGen’s Actionability Working Group. This NIH-funded panel scores the “clinical actionability” of various pathogenic variants, and gives recommendations. Promethease presents this to carriers, as exemplified by the BRCA2 mutation below. Neurodegenerative diseases are largely absent from this ClinGen list, due to the lack of approved drugs, Lennon said.

A Call to Action? Promethease brings in recommendations from ClinGen to help mutation carriers take action to prevent or treat disease.

Even as researchers would like to see DTC companies step up their games on counseling and referral, 23andMe has contributed to research in other areas, especially Parkinson’s. Spurred in part by the discovery that Sergey Brin, the ex-husband of 23andMe founder Anne Wojcicki, carries a pathogenic LRRK2 mutation, 23andMe tackled the genetic architecture of PD. Partnering with the Michael J. Fox Foundation, 23andMe gathered a deeply genotyped and phenotyped cohort of PD patients who have contributed to GWAS, informed biomarker research, and whose DNA is currently being plumbed in search of rare pathogenic variants (Jul 2014 news and Nalls et al., 2015).—Jessica Shugart

References

News Citations

- Mail-In Genome Tests: Do They Measure Up?

- To Know or Not to Know: Trial Participants Confront the Question

- Genentech Strikes Deal with 23andMe to Study Parkinson’s Genomes

- Meet the Artful Leftie: NIH Jump-Starts U.S.-Canadian FTLD Cohorts

- Largest Meta-GWAS Yet Uncovers New Genetic Links to Parkinson’s

Mutations Citations

Basic page Citations

Paper Citations

- Boeldt DL, Schork NJ, Topol EJ, Bloss CS. Influence of individual differences in disease perception on consumer response to direct-to-consumer genomic testing. Clin Genet. 2015 Mar;87(3):225-32. Epub 2014 Jun 6 PubMed.

- Koeller DR, Uhlmann WR, Carere DA, Green RC, Roberts JS, PGen Study Group. Utilization of Genetic Counseling after Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing: Findings from the Impact of Personal Genomics (PGen) Study. J Genet Couns. 2017 May 16; PubMed.

- Vassy JL, Christensen KD, Schonman EF, Blout CL, Robinson JO, Krier JB, Diamond PM, Lebo M, Machini K, Azzariti DR, Dukhovny D, Bates DW, MacRae CA, Murray MF, Rehm HL, McGuire AL, Green RC, MedSeq Project. The Impact of Whole-Genome Sequencing on the Primary Care and Outcomes of Healthy Adult Patients: A Pilot Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Jun 27; PubMed.

- Nalls MA, McLean CY, Rick J, Eberly S, Hutten SJ, Gwinn K, Sutherland M, Martinez M, Heutink P, Williams NM, Hardy J, Gasser T, Brice A, Price TR, Nicolas A, Keller MF, Molony C, Gibbs JR, Chen-Plotkin A, Suh E, Letson C, Fiandaca MS, Mapstone M, Federoff HJ, Noyce AJ, Morris H, Van Deerlin VM, Weintraub D, Zabetian C, Hernandez DG, Lesage S, Mullins M, Conley ED, Northover CA, Frasier M, Marek K, Day-Williams AG, Stone DJ, Ioannidis JP, Singleton AB, Parkinson's Disease Biomarkers Program and Parkinson's Progression Marker Initiative investigators. Diagnosis of Parkinson's disease on the basis of clinical and genetic classification: a population-based modelling study. Lancet Neurol. 2015 Oct;14(10):1002-9. Epub 2015 Aug 10 PubMed.

Other Citations

External Citations

Further Reading

No Available Further Reading

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.