Potential New ALS Gene Leads to Extraordinary Aggregates

Quick Links

A paper in the May 3 Science Translational Medicine identifies a potential new risk gene for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Mutations in ANXA11, which encodes the phospholipid binding protein annexin A11, turned up in people with both familial and sporadic forms of the disease, report scientists led by Christopher Shaw of King’s College London, Vincenzo Silani of the University of Milan, and John Landers of the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester. Mutant proteins strayed from their normal binding partner, the calcyclin protein, and instead aggregated in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Annexin A11 appears to aid in vesicle transport.

“This falls in line with themes we are seeing in all ALS mutations, which are impairments in proteostasis, autophagy, vesicular trafficking, and aggregation,” said Matthew Harms, Columbia University, New York. “It adds some genetic firepower to our interest in those pathways.”

Strange clumps.

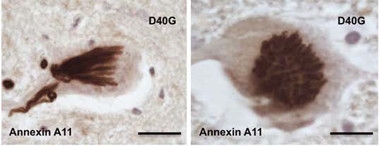

Mutant annexin A11 inclusions take varied forms, including an ordered series of parallel tubules seen from the side (left) and top. [Courtesy of Science Translational Medicine/AAAS.]

This paper lists a handful of co-first authors: Bradley Smith, Simon Topp, and Han-Jou Chen of Kings College, with Claudia Fallini of UMass Worcester, and Hideki Shibata, Nagoya University, Japan. On their hunt for new ALS-associated genes, they analyzed whole exome sequences from 751 patients with familial disease and from 180 with sporadic ALS. They found six rare mutations in annexin A11 in 13 people, including a p.D40G amino acid substitution that segregated with disease in two families. These mutations were absent from 70,000 healthy controls. They clustered at the N-terminal tip of the protein. Previous studies suggest that annexin A11 aids in vesicular transport between the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus (Shibata et al., 2015).

Carriers developed ALS at an average age of 67, with a classic ALS phenotype and primarily bulbar-onset disease, meaning they first had trouble speaking and swallowing. One patient who had the p.D40G mutation donated tissue for postmortem analysis. As is typical in ALS, neuron loss, astrogliosis, and phosphorylated TDP-43 inclusions pervaded their spinal cords; the latter also appeared in the medulla, temporal neocortex, and hippocampus.

The surprise came when the researchers stained for annexin A11. “We saw the most extraordinary inclusions,” Shaw told Alzforum. The skein-like patterns and tubular structures in motor neurons of the spinal cord were a far cry from the disordered blobs of TDP-43 that are typical of ALS neuropathology. They were unlike anything the scientists had ever seen, Shaw said (see image above). Add to that the torpedo-shaped structures in axons of the motor cortex, temporal neocortex, and hippocampus, and Shaw knew they were onto something. “This mutant protein is actually aggregating in our patients,” he said. “That gave me 100 percent confidence that we had found a real gene causing pathology.”

To find out how ANXA11 causes disease, the authors expressed several of the disease-associated variants or the wild-type protein in mouse primary motor neurons. Wild-type annexin A11 appeared in the nucleus, and in large, vesicle-like structures throughout the cytoplasm of the axons, soma, and dendrites. By contrast, the mutant proteins largely stayed out of vesicles; they aggregated instead. Their inclusions trapped functional, wild-type annexin A11 protein, implying they robbed the cell of the function of the normal protein.

The variants also appeared to disrupt Annexin A11 binding to calcylin. Computer modeling predicted that the N-terminus of annexin A11 forms two helices, one in and the other next to the calcyclin binding site. Two of the six mutations appeared to disrupt formation of one of those helices. Immunoprecipitation assays revealed that while wild-type annexin A11 bound calcyclin, those mutants did not. The authors suggested that when annexin A11 cannot bind calcyclin, annexin A11 builds up in the cytoplasm and accumulates. As controls, the authors expressed non-pathogenic annexin A11 variants that appear in the general population; these variants left calcyclin binding intact.

That last step was important, and provides a model for how these assays should be done in the future, said Harms, adding, “It demonstrated that the ALS-specific functional defect was coming from mutations that they found in the patients.” In general, researchers should always compare suspected pathogenic mutations to non-pathogenic ones to avoid assays picking up on nonspecific effects. Harms agreed this paper offers clear evidence that the p.D40G mutation—which segregates with disease and leads to those unusual inclusions—is causative of ALS. More work needs to be done to see if the other five mutations are pathogenic, he said.

Shaw said his collaborators are now making transgenic zebrafish and mouse models with the mutations so they can study them in whole organisms.—Gwyneth Dickey Zakaib

References

Paper Citations

- Shibata H, Kanadome T, Sugiura H, Yokoyama T, Yamamuro M, Moss SE, Maki M. A new role for annexin A11 in the early secretory pathway via stabilizing Sec31A protein at the endoplasmic reticulum exit sites (ERES). J Biol Chem. 2015 Feb 20;290(8):4981-93. Epub 2014 Dec 24 PubMed.

Further Reading

Papers

- Corcia P, Couratier P, Blasco H, Andres CR, Beltran S, Meininger V, Vourc'h P. Genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2017 May;173(5):254-262. Epub 2017 Apr 25 PubMed.

Primary Papers

- Smith BN, Topp SD, Fallini C, Shibata H, Chen HJ, Troakes C, King A, Ticozzi N, Kenna KP, Soragia-Gkazi A, Miller JW, Sato A, Dias DM, Jeon M, Vance C, Wong CH, de Majo M, Kattuah W, Mitchell JC, Scotter EL, Parkin NW, Sapp PC, Nolan M, Nestor PJ, Simpson M, Weale M, Lek M, Baas F, Vianney de Jong JM, Ten Asbroek AL, Redondo AG, Esteban-Pérez J, Tiloca C, Verde F, Duga S, Leigh N, Pall H, Morrison KE, Al-Chalabi A, Shaw PJ, Kirby J, Turner MR, Talbot K, Hardiman O, Glass JD, De Belleroche J, Maki M, Moss SE, Miller C, Gellera C, Ratti A, Al-Sarraj S, Brown RH Jr, Silani V, Landers JE, Shaw CE. Mutations in the vesicular trafficking protein annexin A11 are associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Sci Transl Med. 2017 May 3;9(388) PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.