Pretty in PINK1, Cryo-EM Reveals How Kinase Anchors to Mitochondria

Quick Links

A Parkinsonian mystery—how PINK1 locks onto malfunctioning mitochondria—now has a structural solution. Researchers at the University of Melbourne led by Sylvie Callegari, Alisa Glukhova, and David Komander have captured the first cryo-EM snapshot of human PINK1 bound directly to depolarized mitochondria. Here, the kinase partners with TOM and VDAC, forming a supersized complex that tethers PINK1 to the outer membrane—a crucial first step toward clearing these defective organelles. The study appeared in the March 13 Science.

- PINK1 interacts with mitochondrial membrane gatekeepers.

- It forms a supercomplex with the proteins TOM and VDAC.

- Findings clarify mechanism of PINK1 membrane stabilization.

“This new cryo-EM structure represents a remarkable advance in our understanding of how human PINK1 is stabilized” said Miratul Muqit of the University of Dundee (comment below). “Komander and his team deserve high praise for this work.”

PINK1, a ubiquitin kinase that causes early onset Parkinson’s disease when mutated, functions as an early warning system for faltering mitochondria (Valente et al., 2004). Under normal conditions, when mitochondria maintain a delicate balance of ions inside and outside their double membrane—in other words, their membrane potential—PINK1 is whisked across the outer layer and embeds in the inner. There, it gets cleaved by proteases, and the fragments are soon dispatched back to the cytosol for processing by the proteome.

But when mitochondria lose their charge, this routine grinds to a halt, leaving PINK1 stranded on the outer membrane. From this perch, PINK1’s kinase domain springs into action, phosphorylating ubiquitin, which recruits the ubiquitin ligase Parkin—another PD-linked protein—to tag mitochondria for degradation. While the broad strokes of this process are well-known, precisely how PINK1 remains anchored to the membranes of ailing mitochondria was a puzzle.

To solve it, Callegari and colleagues turned to high-resolution imaging. Using human embryonic kidney cells, scientists transfected in tagged PINK1 and then treated cells with oligomycin A, an ATP synthase inhibitor that depolarizes mitochondria and traps PINK1 at their surface. After lysing the cells and isolating mitochondria, researchers gently solubilized membranes with detergent, pulled down PINK1, and, finally, fractioned these samples with size-exclusion chromatography. Out popped a 750 kDa supercomplex, containing not just multiple translocase components but also VDAC, acylglycerol kinase and a handful of chaperones—all bound together with PINK1 itself.

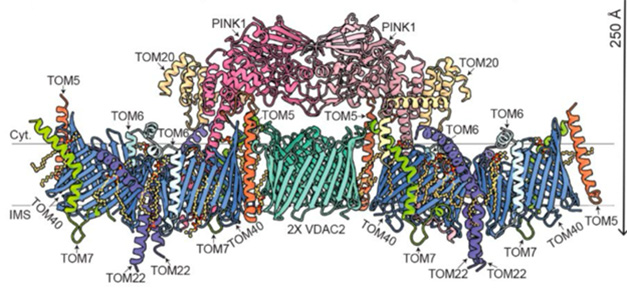

Scaling up this purification allowed the scientists to amass enough protein for Cryo-EM. This revealed a grand assembly, including components of the translocase of the outer membrane (TOM) and of the voltage-dependent anion channels (VDAC) that help maintain the mitochondrial membrane potential.

Two TOM core complexes, each with two copies of TOM40, TOM7, TOM6, TOM5, and TOM22, plus a single TOM20, formed the backbone of the complex. These twin assemblies straddled a central VDAC2 dimer—with TOM5—as the molecular glue. Crowning the assembly, two PINK1 kinase domains lock together in a dimer, anchored in place by interactions with TOM5 and TOM20. Meanwhile, PINK1’s N-termini snaked through the barrel-shaped TOM40 channels, emerging into the intermembrane space, guided by TOM7 and TOM22 (image below). The TOM-VDAC assembly had never been documented before.

Mito Space Invader. Color-coded atomic model of the PINK-TOM-VDAC complex, as viewed from along the plane of the outer membrane. [Courtesy of Callegari et al., Science, 2025.]

“The structure is stunning” said Derek Narenda, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland. “Many of its features are surprising and will undoubtedly reshape our understanding of damage sensing by PINK1” (comment below).

PINK1 Perspectives. Top-down view, as seen from the cytosol (left) ,and bottom-up view, as seen from the mitochondrial inter membrane space (right). [Courtesy of Callegari et al., Science, 2025.]

In this structure, a disulfide bond at cysteine 166 locks each PINK1 together as a dimer (image below). This tandem arrangement echoes the authors’ previous characterization of an insect PINK1 from the body louse (Gan et al., 2022). The arrangement is essential for PINK1 dimers to phosphorylate one another. In the louse, this step triggers a conformational shift that forms a ubiquitin-binding site. Intriguingly, the dimer of louse PINK1 must first break into monomers to phosphorylate ubiquitin. This, in turn, recruits the ubiquitin-ligase Parkin. PINK1 then sticks Parkin with phosphate groups, activating its ligase activity. Picking up the baton, Parkin ligates ubiquitin molecules to damaged mitochondria, tagging them for degradation and recycling.

Kinase Interrupted. Atomic model of PINK1 dimer (in pink, fittingly) overlayed on an outline of the of the TOM-VDAC complex. Disulfide bonds shown as yellow spheres. The dimer is stabilized by the bond at the two Cys166s (in box). [Courtesy of Callegari et al., Science, 2025.]

In the human structure, researchers spotted signs that the kinase domain had shifted toward an activated state, indicating that autophosphorylation had already occurred. They suggest that their snapshot captures PINK1 in a “post-phosphorylation, yet pre-active” conformation, i.e., locked with a disulfide bond and not quite ready to phosphorylate ubiquitin.

Mito Mayday! 1. In healthy mitochondria, PINK1 is swiftly imported to the inner membrane before being chopped up and ejected. 2. Uh oh! A falling mitochondria membrane potential blocks PINK1 import so it piles up on the membrane, where it links up with TOM and VDAC. We’re ready for action. 3. Fire up the kinase: PINK1 cracks apart, phosphorylating ubiquitin molecules on membrane proteins such as VDAC. 4. Parkin joins in: Decked out with phospho-ubiquitin, VDAC draws in Parkin. PINK1 phosphorylates Parkin, activating it to pile on more ubiquitin and signaling for a mitochondrial clean-up. [Courtesy of Callegari et al., Science, 2025.]

What does this mean for Parkinson’s disease? The authors hope their structure will pave the way for developing therapeutic activators that stabilize PINK1 on mitochondria. Muqit agrees, noting that the lack of structural information has hindered efforts to design small molecules that directly target PINK1. He believes this new structure will be a valuable resource. AbbVie is currently recruiting for a second Phase I trial of a small molecule PINK1 activator called ABBV-1088.—George Heaton

George Heaton is a freelance writer in Durham, North Carolina.

References

Paper Citations

- Valente EM, Abou-Sleiman PM, Caputo V, Muqit MM, Harvey K, Gispert S, Ali Z, Del Turco D, Bentivoglio AR, Healy DG, Albanese A, Nussbaum R, González-Maldonado R, Deller T, Salvi S, Cortelli P, Gilks WP, Latchman DS, Harvey RJ, Dallapiccola B, Auburger G, Wood NW. Hereditary early-onset Parkinson's disease caused by mutations in PINK1. Science. 2004 May 21;304(5674):1158-60. Epub 2004 Apr 15 PubMed.

- Gan ZY, Callegari S, Cobbold SA, Cotton TR, Mlodzianoski MJ, Schubert AF, Geoghegan ND, Rogers KL, Leis A, Dewson G, Glukhova A, Komander D. Activation mechanism of PINK1. Nature. 2022 Feb;602(7896):328-335. Epub 2021 Dec 21 PubMed.

External Citations

Further Reading

Papers

- Valente EM, Abou-Sleiman PM, Caputo V, Muqit MM, Harvey K, Gispert S, Ali Z, Del Turco D, Bentivoglio AR, Healy DG, Albanese A, Nussbaum R, González-Maldonado R, Deller T, Salvi S, Cortelli P, Gilks WP, Latchman DS, Harvey RJ, Dallapiccola B, Auburger G, Wood NW. Hereditary early-onset Parkinson's disease caused by mutations in PINK1. Science. 2004 May 21;304(5674):1158-60. Epub 2004 Apr 15 PubMed.

- Gan ZY, Callegari S, Cobbold SA, Cotton TR, Mlodzianoski MJ, Schubert AF, Geoghegan ND, Rogers KL, Leis A, Dewson G, Glukhova A, Komander D. Activation mechanism of PINK1. Nature. 2022 Feb;602(7896):328-335. Epub 2021 Dec 21 PubMed.

Primary Papers

- Callegari S, Kirk NS, Gan ZY, Dite T, Cobbold SA, Leis A, Dagley LF, Glukhova A, Komander D. Structure of human PINK1 at a mitochondrial TOM-VDAC array. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adu6445

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

MRC Protein Phosphorylation and Ubiquitylation Unit

More than a decade ago, Youle, Lazarou, and Matsuda first showed biochemically that human PINK1 is stabilized on the mitochondrial TOM complex. Since then, there has been great interest in understanding the mechanism. This new cryo-EM structure represents a remarkable advance in our understanding of how human PINK1 is stabilized at the TOM complex, and Komander and his team deserve high praise for this work. Consistent with recent biochemical studies, including from our lab, the structure explains how TOM20 stabilizes PINK1 at the complex. But the structure also provides unprecedented new insights about a role for TOM5 in stabilizing PINK1, and about how the N-terminus of PINK1 traverses the TOM40 pore.

This complements a parallel analysis we have undertaken, in which we performed TurboID proximity labelling proteomics of endogenous PINK1 in human cells, observing robust interaction with TOM5, TOM40, and other components (manuscript under preparation). The discovery that PINK1-TOM complex is assembled with VDAC2 is intriguing and raises several important questions, including how ubiquitylation of VDAC2 by Parkin would affect the complex and the ensuant activation of PINK1.

Overall, the PINK1 structure opens many new avenues for investigation and will be a valuable resource for companies developing activators.

National Institutes of Health

Mitochondria produce energy for our cells but are also prone to damage. How does the cell know when a mitochondrion is damaged? One way is through the PINK1-Parkin mitophagy pathway, with PINK1 serving as the damage sensor (reviewed in Narendra and Youle, 2024). PINK1 is targeted to all mitochondria but quickly removed from the surface of healthy mitochondria. In damaged mitochondria, however, PINK1 becomes stuck in the entrance, trapped between the import gates of the outer (TOM complex) and inner (TIM23 complex) mitochondrial membranes. PINK1 so trapped accumulates on the surface, where it activates Parkin to mark the damaged mitochondrion for lysosomal clearance. This cleanup pathway is especially important in long-lived cells like neurons. Indeed, loss of either PINK1 or Parkin function causes Parkinson’s disease.

Although this damage sensing mechanism has been known for over a decade, it had never been seen up close. That is, until this remarkable new article from Sylvie Callegari, Alisa Glukhova, David Komander, and others, in which they provide the first clear view of PINK1 stuck in the import path of a damaged mitochondrion. The structure is stunning. A pair of PINK1 molecules, each sitting in a separate TOM complex, reach across the pore of VDAC2 to make contact.

Many features of the structure are surprising and will certainly reshape how we understand damage sensing by PINK1 as well as mitochondrial import more generally. Perhaps most surprisingly was the presence of a VDAC2 dimer between the PINK1 dimer. Together with the two TOM complex dimers this formed a striking array of six beta-barrel proteins, altogether forming six pores in the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), only two of which were occupied by PINK1.

Also surprising were the specific subunits of the TOM complex that were found to hold PINK1 to the surface. These included not only those long implicated in PINK1 stabilization on the OMM, such as the import receptor TOMM20, and the small subunit TOMM7, but also the small subunit TOMM5. In a recent preprint from my lab, we showed TOMM5 to be required for PINK1 stabilization on the OMM, providing functional validation of this structural observation (Thayer et al., 2025). The structure was also notable for what was absent: namely, another import receptor called TOMM70. TOMM70 has been proposed to be important for PINK1 stabilization on the OMM in some contexts, such as in vitro import assays, and when reconstituting PINK1 stabilization on the OMM in yeast (Raimi et al., 2024; Maruszczak et al., 2022; Kato et al., 2013). Consistent with its absence in this structure, however, it was recently shown not to be required for endogenous PINK1 stabilization or import in human cells (Thayer et al., 2025).

The structure also leaves many questions for future work. Perhaps most tantalizing, PINK1 in the dimer appears to be caught near the end of its brief embrace, during which each molecule phosphorylates the other to complete folding of its substrate binding site. Surprisingly, a disulfide bond links the two in this conformation and presumably must be broken to separate them and free each PINK1 molecule to activate Parkin. How does this happen? Is it a regulated process and, if so, what factor regulates it? And why does it happen? Does it serve as a sort of timer, lending PINK1 the buffer period it needs to mature? As the authors tease at the end of their article, there are more structures to come, and, I suspect, more answers.

References:

Narendra DP, Youle RJ. The role of PINK1-Parkin in mitochondrial quality control. Nat Cell Biol. 2024 Oct;26(10):1639-1651. Epub 2024 Oct 2 PubMed.

Thayer JA, Petersen JD, Huang X, Hawrot J, Ramos DM, Sekine S, Li Y, Ward ME, Narendra DP. Novel reporter of the PINK1-Parkin mitophagy pathway identifies its damage sensor in the import gate. bioRxiv. 2025 Feb 20; PubMed.

Raimi OG, Ojha H, Ehses K, Dederer V, Lange SM, Rivera CP, Deegan TD, Chen Y, Wightman M, Toth R, Labib KP, Mathea S, Ranson N, Fernández-Busnadiego R, Muqit MM. Mechanism of human PINK1 activation at the TOM complex in a reconstituted system. Sci Adv. 2024 Jun 7;10(23):eadn7191. PubMed.

Maruszczak KK, Jung M, Rasool S, Trempe JF, Rapaport D. The role of the individual TOM subunits in the association of PINK1 with depolarized mitochondria. J Mol Med (Berl). 2022 May;100(5):747-762. Epub 2022 Apr 7 PubMed.

Kato H, Lu Q, Rapaport D, Kozjak-Pavlovic V. Tom70 is essential for PINK1 import into mitochondria. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58435. Epub 2013 Mar 5 PubMed.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.