So Far, So Good for Parkinson’s Gene Therapy

Quick Links

Using gene therapy to boost dopamine levels in the brain could soothe the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, according to a March 9 press release. Voyager Therapeutics of Cambridge, Massachusetts, shared interim data from an ongoing, open-label Phase 1b trial that is testing VY-AADC, a treatment designed to boost the conversion of orally administered levodopa into dopamine. People with advanced PD who received the therapy needed less levodopa, and had fewer side effects commonly associated with this standard therapy. They also reported longer periods of time without debilitating movement problems, as well as improved quality of life. The findings suggest that the gene therapy might maximize the benefits, and reduce the side effects, of levodopa treatment.

- Gene therapy enhances dopamine production in the putamen.

- PD patients tolerated the treatment, needed less levodopa, and had better motor function and quality of life.

- A Phase 2/3 trial is planned for later this year.

Dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra (SN) degenerate in PD, and symptoms arise when neurons in the neighboring putamen do not receive sufficient dopamine. As the disease progresses, patients take levodopa to compensate. However, levodopa must be converted into dopamine by aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC), an enzyme produced by substantia nigra neurons but in short supply in the putamen (Ciesielska et al., 2017). As AADC-producing SN neurons wither, so does the effectiveness of levodopa. The drug also triggers side effects that worsen with time, most notably involuntary movements called dyskinesia.

Voyager aims to sidestep the dying SN neurons and directly jack up levels of AADC in the putamen. VY-AADC is an adeno-associated virus (AAV) containing the AADC gene. Voyager originally acquired the vector through a collaboration with Sanofi Genzyme, but now has full worldwide development rights for the treatment. In the Phase 1b trial, 15 participants in three separate cohorts received a single injection of the virus into the putamen. At an estimated 7.5 x 1011 vector genomes (vg) per putamen, participants in Cohort 1 received the lowest dose. Cohorts 2 and 3 received 1.5 and 4.5 x 1012 vg, respectively. Cohorts 1, 2, and 3 received the injections three years, 18 months, and 12 months prior to the current analysis, respectively. The interim data included longitudinal assessments of safety and tolerability (the primary outcomes of the trial), as well as numerous secondary measures aimed at sniffing out any therapeutic effects of the therapy.

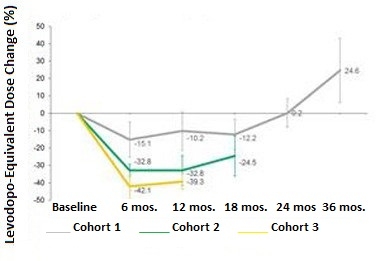

Dropping Doses.

Participants in all three cohorts needed less levodopa in the months following gene therapy, but gradually increased their doses later. [Courtesy of Voyager Therapeutics.]

For the most part, the surgical procedure was well tolerated, and 14 out of 15 patients left the hospital within two days. However, one patient had a pulmonary embolism, most likely arising from a clot that formed in the legs while the patient was immobilized during the injection procedure. Treatment with anti-coagulants resolved the problem and the patient survived. The injection protocol has since been modified to reduce the risk of this happening again.

Using diaries, the participants also recorded more hours per day spent without movement problems than before the therapy. This included a reduction in “off time” spent with PD symptoms, i.e., when levodopa wears off between doses. Cohorts 1, 2, and 3 had 30, 65, and 12 percent reductions in this measure. All cohorts also had a reduction in dyskinesia triggered by the levodopa treatment itself, with the strongest effect in Cohort 2: 18 months after treatment, these participants managed 3.5 more hours per day of on-time without troublesome dyskinesia. At three years, Cohort 1 had 2.1 hours more symptom-free on-time than at baseline, while at 12 months after treatment Cohort 3 had 1.5 hours more. Cohort 3’s improvement leveled off between six and 12 months, however (see graph below).

Following the gene therapy treatment, patients were asked to adjust their doses of levodopa to maintain maximal benefits with minimum side effects, in consultation with their neurologist. Participants in all three cohorts lowered their doses of the levodopa over the first six months. The extent of the reduction correlated with the dose of VY-AADC. Following a nadir, participants started gradually increasing their doses again. In a conference call, investigators from Voyager speculated that this increase likely reflected desensitization of dopamine receptors in the putamen, an expected consequence of heightened levels of dopamine bathing the neurons there. Notably, in Cohorts 2 and 3 at 12 months and 18 months, respectively, participants’ levodopa doses still remained lower than baseline, while those in Cohort 1 were 25 percent higher than baseline (see graph below). PD patients typically need more levodopa as the disease progresses. Previously, researchers reported that the vector continues to produce AADC for up to four years after injection (Mittermeyer et al., 2012). Voyager used 18F-DOPA PET imaging to monitor AADC, but did not share that data in the current press release.

Fewer Side Effects.

While on levodopa, participants experienced longer periods without troublesome side effects of the treatment. [Courtesy of Voyager Therapeutics.]

The researchers pointed out that Cohort 3 participants had started the trial with more severe levodopa-induced dyskinesia. They also received the highest dose of the gene therapy, and therefore reduced their levodopa doses more than either of the other cohorts. This could have resulted in greater fluctuations in their motor symptoms, the investigators speculated. Therefore, they interpreted Cohort 2, which had a substantial reduction in levodopa dosage and significant improvement in motor symptoms, as the likely “sweet spot” in VY-AADC dosage.

All three cohorts reported improvements in quality of life questionnaires from baseline to six months, with Cohorts 2 and 3 continuing to improve between six and 12 months following their VY-AADC injections.

Voyager plans to start a larger Phase 2/3 trial to assess the efficacy of VY-AADC by mid-2018. They will use data from the Phase 1b trial to pick the optimum dose. The company is also conducting a small Phase 1 trial to compare delivery of the drug via different injection sites. Depending on the upcoming results of that study, the investigators may change the injection site from the top to the back of the head in the Phase 2/3 trial.—Jessica Shugart

References

Paper Citations

- Ciesielska A, Samaranch L, San Sebastian W, Dickson DW, Goldman S, Forsayeth J, Bankiewicz KS. Depletion of AADC activity in caudate nucleus and putamen of Parkinson's disease patients; implications for ongoing AAV2-AADC gene therapy trial. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0169965. Epub 2017 Feb 6 PubMed.

- Mittermeyer G, Christine CW, Rosenbluth KH, Baker SL, Starr P, Larson P, Kaplan PL, Forsayeth J, Aminoff MJ, Bankiewicz KS. Long-term evaluation of a phase 1 study of AADC gene therapy for Parkinson's disease. Hum Gene Ther. 2012 Apr;23(4):377-81. Epub 2012 Apr 10 PubMed.

External Citations

Further Reading

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.