ROCK’n the Tau Pathway?

Quick Links

A kinase inhibitor that is an approved medication for people and improves memory in rats also promotes degradation of toxic tau in lab models, according to a paper in the January 27 Journal of Neuroscience. Inhibiting the Rho-associated protein kinases ROCK1 and ROCK2 with the drug fasudil got rid of tau in cultured human neurons and the eyes of fruit flies, report senior author Jeremy Herskowitz and colleagues from the University of Alabama in Birmingham. Fasudil is a vasodilator approved in Japan and China to prevent tightening of arteries and ischemia following surgery in the subarachnoid space surrounding the brain. It has undergone preclinical investigation in several neurodegenerative conditions thanks to its effects on autophagy and inflammation. The drug, or related compounds, might be more broadly applicable to prevent a variety of tauopathies, Herskowitz suggested. Alas, efforts to study fasudil in those diseases have been limited thus far.

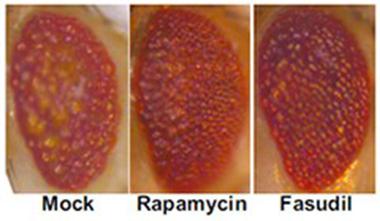

Looking good.

The compound eyes of fruit flies overexpressing human tau degenerate when treated with solvent only (mock, left). They improve when treated with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin (middle) or the Rho kinase inhibitor fasudil (right). [Courtesy, with permission: Gentry et al., 2016, http://www.jneurosci.org/content/36/4/1316.short?sid=fce4c5eb-fc78-4769-...

Scientists suspect that if they could reduce toxic forms of tau, they might be able to prevent or treat tau-based neurodegeneration. Tau researchers have been interested in Rho kinases for more than a decade, Herskowitz said, ever since the discovery that the ROCKs can phosphorylate tau and diminish its ability to assemble the cytoskeleton (Amano et al., 2003). Inhibiting Rho kinases also stimulates cells to degrade aggregated, mutant huntingtin protein (Bauer et al., 2009). However, scientists have not fully worked out the pathway between Rho kinases, tau, and degradation.

Tau Takedown

In the new study, first author Erik Gentry and colleagues focused on ROCKs in tauopathies that are due to accumulation of tau containing four microtubule-binding repeats (4R tau). A 3R version of tau is also elevated in some neurodegenerative diseases; for example, both forms accumulate in Alzheimer’s disease. The scientists analyzed autopsy brain tissue from nine people with corticobasal degeneration (CBD) and nine with progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). Both are subtypes of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) that affect movement as well as thinking, vision, speech, and swallowing. Compared to 10 control brains, the FTD tissues contained more insoluble tau and more of both ROCK1 and ROCK2.

If excess ROCKs were associated with excess tau, might decreasing them curtail it? Gentry and colleagues used small interfering RNAs to ROCK1 or ROCK2 to tune down expression in human neuroblastoma cultures. Levels of endogenous tau dropped by one-third in the ROCK1 and by two-thirds in the ROCK2 knockdown cells. The authors suspected that tau was getting routed into either the proteasome or the autophagy pathway, so they treated the knockdown cultures with MG132, which obstructs the proteasome, or bafilomycin, which hinders autophagy. Only bafilomycin altered tau concentrations, increasing them in the knockdown cells. “That suggested that if you reduce expression of the Rho kinases, then it stimulates autophagy and that degrades tau,” concluded Herskowitz.

However, the scientists did not know how the ROCKs ramped up tau autophagy. Was their kinase activity required? ROCK2 had the stronger effect, so to assess the role of phosphorylation by this enzyme the authors expressed a kinase-dead version of ROCK2 in the knockdown cultures. It did not change tau expression, indicating that ROCK2 indeed phosphorylates a substrate to protect tau from degradation.

The authors have not yet determined if ROCK2 acts on tau itself or an intermediary. Even so, they discovered that ROCK2 knockdown reduced levels of p70 S6 kinase. S6K phosphorylates the kinase mTOR, which in turn suppresses autophagy, and ROCK2 knockdown also resulted in reduced mTOR phosphorylation. Thus, Gentry and colleagues hypothesize a pathway in which ROCK2 inhibition leads to less S6K, reducing phosphorylation of mTOR, and elevating autophagy of tau.

The chemical structure of fasudil.

Inhibiting Rho kinases with the drug fasudil should have the same effects as the siRNA knockdown, the authors reasoned. Indeed, treating wild-type mouse primary cortical neurons with the drug increased levels of the autophagy marker LC3-II, and lessened both soluble and insoluble tau, they report. Then Gentry and colleagues tested fasudil in a Drosophila line expressing human 4R tau in its eyes. This causes degradation and buildup of autophagic vacuoles (see image above). Treating the flies before they emerged from their pupae, the authors found that the eyes of fasudil-treated flies looked more intact, and contained 60 percent less tau, than the eyes of untreated flies.

The study drew praise from Matt Huentelman of the Translational Genomics Research Institute in Phoenix, who was not involved in it. Huentelman suggested fasudil might work best if given before neurodegeneration takes off. Herskowitz believes ROCK inhibition has promise to alleviate 4R tauopathies, and likely 3R ones as well. Next, he plans to try to treatment in mouse tauopathy models.

“I think if there were some compelling results in preclinical models, it could be worth pursuing,” commented Marc Diamond of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. Diamond did not participate in the study but has used fasudil to protect the eyes of a Huntington’s disease model (Li et al., 2013). He noted that without understanding the mechanism by which fasudil promotes tau autophagy, it could be difficult to monitor the drug’s effects in people, unless the treatment cuts down on tau in the cerebrospinal fluid. “Certainly, it would be very interesting to study chronic administration of this compound in mouse models,” Diamond told Alzforum.

Too Good to Be True?

In Japan and China, physicians mainly prescribe fasudil as a vasodilator to improve blood flow in the brain; specifically, it helps prevent constriction of blood vessels after surgery, for example, to repair a ruptured aneurysm. Preclinical and some small clinical studies also indicated ROCK inhibitors might help with cardiovascular diseases, including heart failure, stroke, and pulmonary hypertension (high blood pressure in the lungs; reviewed in Shi and Wei, 2013). Fasudil is not being extensively studied in North America, though one trial in vascular heart surgery is ongoing.

There are other approaches to taming tau (see Dec 2015 news; Sep 2013 news; Feb 2009 news). Huentelman said that compared with those, fasudil seems to work several steps removed by inhibiting kinases upstream of tau itself. “This might have more side effects, but that remains to be seen,” he said. Fasudil is considered safe in humans, but Huentelman noted that it is typically used only briefly, not for chronic or preventative treatment.

Fasudil’s safety profile for short-term, repeated use appears good, noted Paul Lingor of the University of Göttingen, Germany, who did not participate in the study. After all, Fasudil has been used in Japan since 1995. In a study of people with chest pain, 41 took escalating doses oral fasudil, up to 80 milligrams thrice daily, for eight weeks. Side effects were mild or moderate, and similar between fasudil and placebo recipients. People on fasudil did report a slight increase in skin problems, such as rashes, and vascular disorders, such as bruising from bleeding beneath the skin (Vicari et al., 2005).

However, physicians have occasionally reported more serious concerns in people who received the drug for its approved use, including bleeding in the brain and convulsions (Ishihara et al., 2012; Enomoto et al., 2010). Fasudil is also used after surgery in China, and Dongsheng Fan of Peking University in Beijing told Alzforum side effects include bleeding in the brain as well as other locations, such the digestive tract. Lei Wei of Indiana University School of Medicine noted that fasudil alters the cytoskeleton, which could have repercussions for cellular functions such as adhesion and motility. “I think that chronic treatment of this drug may have side effects on multiple systems,” she speculated. Neither Wei nor Fan collaborated with Herskowitz.

Besides promoting autophagy, as Herskowitz reported, fasudil tamps down inflammation, making it of interest to scientists studying neurodegenerative diseases. Lingor commented that the new paper adds to the data that ROCK inhibitors and fasudil have a role to play in neurodegeneration.

For example, Fan speculated it might also break down TDP-43, which aggregates in some forms of FTD and most kinds of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Fan told Alzforum that he and colleagues have been observing nine people with ALS treated with fasudil, and 18 untreated controls, for more than six months. They measured slope of decline on the ALS Functional Rating Scale, which scores how well people perform basic functions like eating and dressing. The drug was safe and seemed to be effective at three months, but that improvement was no longer significant after six months, Fan told Alzforum. Nonetheless, he now plans a further study in which 10 people with ALS take fasudil for 14 days, compared to historical controls.

Lingor, too, is going after neurodegeneration with fasudil. He found it protects dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s model mice, and extends survival of ALS mouse models (Tönges et al., 2012; Tönges et al., 2014). Lingor told Alzforum he is planning several clinical trials to test fasudil in people with ALS or Parkinson’s.

In 2009, Huentelman reported testing fasudil as a cognitive enhancer in wild-type rats. The drug improved their ability to learn and remember mazes, winding back the aging clock so older rats performed like young ones (Huentelman et al., 2009). Though Huentelman did not analyze tau in the treated animals, he speculated to Alzforum that the mechanism for cognitive enhancement might involve tau.

“Fasudil might be an exciting compound. Imagine if it were pro-cognition and also anti-neurodegeneration,” Huentelman said. “It seems like fasudil is too good to be true.” Huentelman was unable to obtain the drug maker’s sanction for human trials; he said there were concerns about a use so different from vasodilation. Therefore, TGen is testing related compounds in rodents, he told Alzforum.

In fact, fasudil has never been approved for any indication in the United States. Its maker, Asahi Kasei Pharma Corporation, headquartered in Tokyo, attempted to apply for FDA approval by partnering with the American company CoTherix in 2006. That attempt ended a year later when Actelion, the Swiss maker of a competing drug, killed the program after acquiring CoTherix. Actelion publicly said it had discontinued the fasudil project over concerns about kidney toxicity and a payment dispute over supplies. Asahi Kasei believed Actelion wanted to get rid of a possible competitor and sued in 2008. In 2011, a jury awarded $547 million in damages to the Japanese drug maker, later reduced by the court to $416 million. Actelion appealed but the California Supreme Court declined to hear the appeal in 2014. With fasudil’s patent due to expire this year, other pharmaceutical companies may not find it profitable to explore additional indications for this drug (Quora; Forbes; Asahi Kasei press release).

Huentelman suggested an important next step will be to develop more potent inhibitors specific for only ROCK1 or ROCK2.—Amber Dance

References

News Citations

- Protecting Proteasomes from Toxic Tau Keeps Mice Sharp

- Chaperone “Saves” Tau, Turning it into Toxic Oligomers

- Garbage BAG2 Takes Out the Tau

Paper Citations

- Amano M, Kaneko T, Maeda A, Nakayama M, Ito M, Yamauchi T, Goto H, Fukata Y, Oshiro N, Shinohara A, Iwamatsu A, Kaibuchi K. Identification of Tau and MAP2 as novel substrates of Rho-kinase and myosin phosphatase. J Neurochem. 2003 Nov;87(3):780-90. PubMed.

- Bauer PO, Wong HK, Oyama F, Goswami A, Okuno M, Kino Y, Miyazaki H, Nukina N. Inhibition of Rho kinases enhances the degradation of mutant huntingtin. J Biol Chem. 2009 May 8;284(19):13153-64. Epub 2009 Mar 11 PubMed.

- Li M, Yasumura D, Ma AA, Matthes MT, Yang H, Nielson G, Huang Y, Szoka FC, LaVail MM, Diamond MI. Intravitreal administration of HA-1077, a ROCK inhibitor, improves retinal function in a mouse model of huntington disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56026. PubMed.

- Shi J, Wei L. Rho kinases in cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology: the effect of fasudil. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2013 Oct;62(4):341-54. PubMed.

- Vicari RM, Chaitman B, Keefe D, Smith WB, Chrysant SG, Tonkon MJ, Bittar N, Weiss RJ, Morales-Ballejo H, Thadani U, Fasudil Study Group. Efficacy and safety of fasudil in patients with stable angina: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005 Nov 15;46(10):1803-11. Epub 2005 Oct 19 PubMed.

- Ishihara M, Yamanaka K, Nakajima S, Yamasaki M. Intracranial hemorrhage after intra-arterial administration of fasudil for treatment of cerebral vasospasm following subarachnoid hemorrhage: a serious adverse event. Neuroradiology. 2012 Jan;54(1):73-5. Epub 2011 Mar 24 PubMed.

- Enomoto Y, Yoshimura S, Yamada K, Iwama T. Convulsion during intra-arterial infusion of fasudil hydrochloride for the treatment of cerebral vasospasm following subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2010 Jan;50(1):7-11; discussion 11-2. PubMed.

- Tönges L, Frank T, Tatenhorst L, Saal KA, Koch JC, Szego ÉM, Bähr M, Weishaupt JH, Lingor P. Inhibition of rho kinase enhances survival of dopaminergic neurons and attenuates axonal loss in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2012 Nov;135(Pt 11):3355-70. Epub 2012 Oct 19 PubMed.

- Tönges L, Günther R, Suhr M, Jansen J, Balck A, Saal KA, Barski E, Nientied T, Götz AA, Koch JC, Mueller BK, Weishaupt JH, Sereda MW, Hanisch UK, Bähr M, Lingor P. Rho kinase inhibition modulates microglia activation and improves survival in a model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Glia. 2014 Feb;62(2):217-32. Epub 2013 Dec 6 PubMed.

- Huentelman MJ, Stephan DA, Talboom J, Corneveaux JJ, Reiman DM, Gerber JD, Barnes CA, Alexander GE, Reiman EM, Bimonte-Nelson HA. Peripheral delivery of a ROCK inhibitor improves learning and working memory. Behav Neurosci. 2009 Feb;123(1):218-23. PubMed.

External Citations

Further Reading

Papers

- Liu FT, Yang YJ, Wu JJ, Li S, Tang YL, Zhao J, Liu ZY, Xiao BG, Zuo J, Liu W, Wang J. Fasudil, a Rho kinase inhibitor, promotes the autophagic degradation of A53T α-synuclein by activating the JNK 1/Bcl-2/beclin 1 pathway. Brain Res. 2016 Feb 1;1632:9-18. Epub 2015 Dec 10 PubMed.

- Tönges L, Günther R, Suhr M, Jansen J, Balck A, Saal KA, Barski E, Nientied T, Götz AA, Koch JC, Mueller BK, Weishaupt JH, Sereda MW, Hanisch UK, Bähr M, Lingor P. Rho kinase inhibition modulates microglia activation and improves survival in a model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Glia. 2014 Feb;62(2):217-32. Epub 2013 Dec 6 PubMed.

- Raad M, El Tal T, Gul R, Mondello S, Zhang Z, Boustany RM, Guingab J, Wang KK, Kobeissy F. Neuroproteomics approach and neurosystems biology analysis: ROCK inhibitors as promising therapeutic targets in neurodegeneration and neurotrauma. Electrophoresis. 2012 Dec;33(24):3659-68. PubMed.

- Hou Y, Zhou L, Yang QD, Du XP, Li M, Yuan M, Zhou ZW. Changes in hippocampal synapses and learning-memory abilities in a streptozotocin-treated rat model and intervention by using fasudil hydrochloride. Neuroscience. 2012 Jan 3;200:120-9. PubMed.

- Couch BA, DeMarco GJ, Gourley SL, Koleske AJ. Increased dendrite branching in AbetaPP/PS1 mice and elongation of dendrite arbors by fasudil administration. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(4):1003-8. PubMed.

- Sheikh AM, Nagai A, Ryu JK, McLarnon JG, Kim SU, Masuda J. Lysophosphatidylcholine induces glial cell activation: role of rho kinase. Glia. 2009 Jun;57(8):898-907. PubMed.

- Liu FT, Yang YJ, Wu JJ, Li S, Tang YL, Zhao J, Liu ZY, Xiao BG, Zuo J, Liu W, Wang J. Fasudil, a Rho kinase inhibitor, promotes the autophagic degradation of A53T α-synuclein by activating the JNK 1/Bcl-2/beclin 1 pathway. Brain Res. 2016 Feb 1;1632:9-18. Epub 2015 Dec 10 PubMed.

- Song Y, Chen X, Wang LY, Gao W, Zhu MJ. Rho Kinase Inhibitor Fasudil Protects against β-Amyloid-Induced Hippocampal Neurodegeneration in Rats. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2013 Aug;19(8):603-10. PubMed.

Primary Papers

- Gentry EG, Henderson BW, Arrant AE, Gearing M, Feng Y, Riddle NC, Herskowitz JH. Rho Kinase Inhibition as a Therapeutic for Progressive Supranuclear Palsy and Corticobasal Degeneration. J Neurosci. 2016 Jan 27;36(4):1316-23. PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

Takeda

Biogen

Gentry et al.’s discovery that Rho-associated protein kinases (ROCK1 and ROCK2) associate with corticobasal degeneration (CBD) and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) adds to the growing list of neurodegenerative diseases in which ROCK hyperactivity has been implicated as a contributor to the neurodegenerative process. Specifically, the authors demonstrate an upregulation of the ROCK2–S6K–pmTOR axis in CBD and PSP and propose a mechanism by which autophagy is inhibited as a result of S6K-mediated pmTOR activation, consequently leading to tau accumulation. In support of their hypothesis, knockdown of ROCK2, or pharmacological inhibition with a selective ROCK2 inhibitor, reduced levels of tau in neuronal cells and ameliorated tau pathology in a Drosophila model.…More

ROCK kinases are at the center of a number of molecular networks and several studies suggest ROCK inhibition benefits animal models of various neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s disease, multiple sclerosis, spinal muscular atrophy, and ALS. It is important to note that a number of different pathways by which ROCK inhibition may have beneficial effects were proposed in these studies, including direct and indirect effects on axonal regeneration and outgrowth, neuronal survival, change in microglial activation status, and pathological protein aggregation.

As such, ROCK presents an interesting molecular target for the treatment of diseases such as AD, where ROCK inhibition appears to have beneficial effects on both Aβ and tau accumulation, suggesting it may have potential for other tauopathies, including forms of frontotemporal dementia; the results presented by Gentry and colleagues speak to this possibility. However, poor isoform selectivity and potential inhibition of peripheral targets may cause detrimental side effects that prohibit the systemic application of small molecule inhibitors of ROCK in these chronic diseases. Human experience with ROCK inhibitors such as fasudil, which is approved in Japan for the treatment of post-subarachnoid hemorrhage vasospasm, and experimental ROCK inhibitors currently in clinical trials in various indications such as glaucoma, pulmonary artery hypertension, Raynaud’s syndrome, and malignant diseases, is still limited and virtually non-existent in the case of neurodegenerative diseases. However, accumulating data from in vitro and in vivo studies, such as this one published by Gentry et al., highlight ROCK inhibition as a worthwhile target for drug discovery and future clinical development in neurodegenerative diseases.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.