Out With the Old, In With the New—Neurogenesis Refreshes Memories

Quick Links

Fledgling neurons in the hippocampus are thought to play a major role in laying down new memories. Now, a study suggests that neurogenesis also makes us quickly forget. In the May 9 Science, researchers led by Sheena Josselyn and Paul Frankland, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, report that boosting neurogenesis erased recently formed memories in mice, while shutting it down retained them. The authors claim that this forgetting is a good thing. “For optimum memory functioning, you need a healthy balance between forgetting and remembering,” said Frankland. “Neurogenesis may facilitate that balance.”

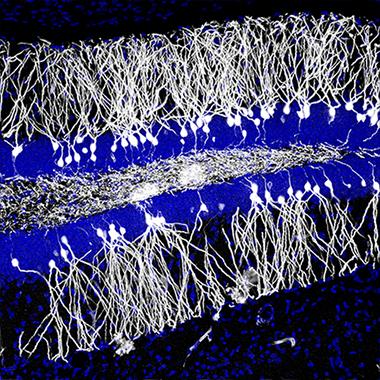

Newborn neurons (white) integrate into the hippocampus. [Image by Jason Snyder.]

Frankland's group first stumbled upon the possibility of neurogenesis-linked forgetting in an unrelated experiment. They noticed that when mice exercised after being trained for a cognitive test, they forgot what they had learned. The scientists could make little sense of the finding based on the known literature, which indicates that exercise induces the birth of new cells in the hippocampus, and that helps mice make new memories (for a review, see Deng et al., 2010). However, few studies had examined how neurogenesis affected previously encoded memories. Could the connections of newly formed cells edge out old links? Scientists had previously speculated about the possibility (see Weisz and Argibay, 2012), but no one had yet put the theory to the test.

To investigate, joint first authors Katherine Akers, Alonso Martinez-Canabal, and Leonardo Restivo trained adult mice in a contextual fear-conditioning task. They then placed the mice back in their home cages, where half had access to a running wheel. Over six weeks, the active mice made more new neurons in the hippocampus, as evidenced by an uptick in Ki67 and doublecortin, markers of proliferation and immature neurons, respectively. When the researchers tested the mice again, those that had exercised were less fearful, suggesting neurogenesis ablated their memories.

To test whether the effect of exercise was due to neurogenesis, Akers and colleagues treated the mice with memantine and fluoxetine, two drugs that induce the birth of new neurons. These drugs erased memories as well. The authors also turned off neurogenesis in mice using the anti-viral medication ganciclovir, which disrupts DNA replication and cell proliferation. After that treatment the mice remembered the fear stimulus whether they had access to running wheels or not, suggesting they remember better when neurogenesis is suppressed.

What about infants? Unlike adults, youngsters churn out lots of newborn neurons and do not form lasting memories (see Josselyn et al., 2012). Would lowering those high rates of neurogenesis help baby mice remember? To find out, the scientists gave mouse pups the antiviral drug after contextual fear conditioning. Without treatment, the memory lasted a day. Given ganciclovir, the mice retained the fear memory for a week after training, suggesting that suppressing neurogenesis helped them remember. In contrast, infant guinea pigs and rodents called degus produce few new neurons after birth. Both species easily remembered either a foot shock or the location of a hidden platform in the Morris water maze, Akers and colleagues report. However, if the scientists stimulated neurogenesis with exercise or memantine, the rodents forgot the recently learned information.

How could neurogenesis erase memories? The authors hypothesize that as newborn neurons infiltrate the hippocampus and connect with other cells, they crowd out old connections and cause encoded information to be lost (for a review, see Frankland et al., 2013). Older memories that become consolidated or are stored outside the hippocampus are less vulnerable, hence less prone to being forgotten, Frankland said.

Frankland is unsure how his result might extend to aging and Alzheimer’s disease. He speculated that less neurogenesis in older people could leave too much “clutter” lying around in the hippocampus, so that it encodes new information less efficiently. He has no plans to test how neurogenesis affects memories as people age, but is working to characterize lifelong neurogenesis in degus, the only rodent to naturally develop amyloid plaques and tau deposits (see Aug 2012 news story). This survey could provide a backdrop for future studies on neurogenesis and cognitive decline, Frankland said.

The findings make sense in light of previous research, said some scientists interviewed for this article. Justin Rhodes, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, noted that he and others found that mice that exercised after, not before, being hooked on drugs lost their preference for a cocaine-laced environment (see Mustroph et al., 2011). Though they had tied this plasticity to neurogenesis, no one had explicitly implicated forgetting in this type of experiment, he said.

Orly Lazarov, University of Illinois at Chicago, wonders whether neurogenesis causes amnesia in adult mice, as Frankland suggests, or the two experiences of fear conditioning and exercise simply interfere with each other. The fear memories may just take longer to consolidate because the added exercise complicates the learning process, she proposed.

Other scientists wondered which cell populations might be responsible for the forgetting. Frankland focused on the proliferating and immature cells, but others were not so sure. “The mature neurons are the ones that integrate into neural circuitry and are, we believe, most important for memory formation,” said Tess Briones, Wayne State University, Detroit. She would be interested to know how the newborn neurons that go on to mature might go about dismantling memories.

Neurogenesis’ ability to disrupt old memories could potentially help treat post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), when people generally want to forget a recent event, suggested Brian Christie, University of Victoria, British Columbia. If confirmed, the study might even hint about when students should fit exercise into their schedules. They may want to skip the gym when cramming around finals week.—Gwyneth Dickey Zakaib

References

News Citations

Paper Citations

- Deng W, Aimone JB, Gage FH. New neurons and new memories: how does adult hippocampal neurogenesis affect learning and memory?. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010 May;11(5):339-50. PubMed.

- Weisz VI, Argibay PF. Neurogenesis interferes with the retrieval of remote memories: forgetting in neurocomputational terms. Cognition. 2012 Oct;125(1):13-25. Epub 2012 Jul 28 PubMed.

- Josselyn SA, Frankland PW. Infantile amnesia: a neurogenic hypothesis. Learn Mem. 2012 Aug 16;19(9):423-33. PubMed.

- Frankland PW, Köhler S, Josselyn SA. Hippocampal neurogenesis and forgetting. Trends Neurosci. 2013 Sep;36(9):497-503. Epub 2013 Jun 12 PubMed.

- Mustroph ML, Stobaugh DJ, Miller DS, DeYoung EK, Rhodes JS. Wheel running can accelerate or delay extinction of conditioned place preference for cocaine in male C57BL/6J mice, depending on timing of wheel access. Eur J Neurosci. 2011 Oct;34(7):1161-9. Epub 2011 Aug 22 PubMed.

Further Reading

Primary Papers

- Akers KG, Martinez-Canabal A, Restivo L, Yiu AP, De Cristofaro A, Hsiang HL, Wheeler AL, Guskjolen A, Niibori Y, Shoji H, Ohira K, Richards BA, Miyakawa T, Josselyn SA, Frankland PW. Hippocampal neurogenesis regulates forgetting during adulthood and infancy. Science. 2014 May 9;344(6184):598-602. PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.