Exercise May Not Keep People Sharp After All, Meta-Analysis Says

Quick Links

Exercise makes for a healthy body. But does it also keep people’s minds sharp as they get older? Past clinical trials suggested as much, but a new meta-analysis says no. Luis Ciria and Daniel Sanabria at the University of Granada, Spain, led the analysis of more than 100 randomized-control trials on exercise and cognition in healthy people of all ages. In the March 27 Nature Human Behavior, they reported little, if any, cognitive improvements from physical activity after correcting for differences between intervention and control groups in baseline statistics and methodology. These results don’t mean that exercise doesn’t help the mind, just that no one has proven it, the authors say.

- Scientists amalgamated 24 meta-analyses of 109 exercise trials.

- They calculated a small improvement in cognition.

- This effect all but disappeared after correcting for bias and methodology.

- The analysis underscores the need for better harmonization of exercise trials.

Philip Gasquoine of the University of Texas, Rio Grande Valley, agreed, stressing the distinction between exercise improving cognition and improving health. “Regular exercise doesn’t make a healthy person smarter, but we know it helps stave off Alzheimer’s disease in older adults, based on epidemiological studies,” he told Alzforum. Others disagreed with the authors’ conclusions. “I do not find this study convincing,” wrote Yaakov Stern of Columbia University, New York, and Michael Borenstein of Biostat Inc., Englewood, New Jersey (comment below).

Teresa Liu-Ambrose of the University of British Columbia in Canada thought the analysis indicated that exercise has a positive, but small, effect on cognitive abilities. She also emphasized that being active is within a person’s control and can negate the other side of the coin, namely inactivity. “Exercise directly combats physical inactivity, which is a key and modifiable risk factor for dementia, as highlighted by the Lancet 2020 report,” she wrote (comment below; Aug 2020 news; Jul 2022 news).

Epidemiological evidence that exercise helps maintain a healthy brain has grown over the past 30 years. Among cognitively normal older adults, exercisers slip half as much on cognitive tests and fend off dementia longer than their sedentary counterparts, even when they had high levels of total tau in their plasma or amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in their brains (Aug 2021 news; Jan 2019 news). Alas, this evidence comes from dozens of often small randomized control trials that test a variety of interventions, using different protocols and outcome measures, making comparisons difficult.

To evaluate these data, first author Ciria carried out an umbrella analysis of 24 prior meta-analyses of 109 RCTs conducted from 1989 to 2020. They involved 11,266 healthy people aged 6 to mid-80s, though each trial was relatively small, averaging 78 participants. Each meta-analysis included an average of 11 trials, with most involving two to 30 studies.

Across the RCTs, exercise interventions lasted anywhere from a couple of weeks to a few months and entailed various activities at different intensities. There were different control protocols, with some involving no activity and others a stretching regimen. Outcomes measured different cognitive domains, though most focused on global cognition or executive function, and used various cognitive tests.

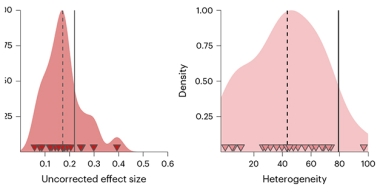

While some of the meta-analyses included trials that enrolled people with mild cognitive impairment, Ciria and colleagues reanalyzed the data using only studies of healthy people. The median effect size was 0.17 on the Cohen’s d scale, meaning exercise improved cognitive function slightly. The larger the Cohen’s d value, the more one variable influences another, with values above 0.7 indicating a strong effect (see image below). Stern and Borenstein noted that these were just the average effect sizes and that some meta-analyses report values close to 0.5. “It would be important to identify factors in studies that are associated with larger versus smaller effect sizes,” they wrote.

Ciria and colleagues cautioned that when effect sizes are this small, studies are often insufficiently powered to measure the effect accurately. In fact, by their calculations, only two of the 109 studies were sufficiently powered.

Small Effect? The median Cohen’s d effect size (left) of exercise on cognition in healthy people from 24 meta-analyses (triangles) was 0.17 (dashed line). When all 109 clinical trials from the analyses were pooled, the effect size increased a bit (solid line). Heterogeneity among the trials (right) explains 42 percent of the variability between meta-analyses. This almost doubles in reanalysis of all 109 trials (solid line). [Courtesy of Ciria et al., Nature Human Behavior, 2023.]

To look at the data more broadly, the authors pooled all 109 RCTs together for their own giant meta-analysis. This gave a similar median effect size of 0.22. However, when the authors corrected for baseline differences in cognitive test scores and whether the control activity was passive or active, the effect size dropped to 0.13. When they accounted for sample size, because small studies tend to overinflate outcomes, the Cohen’s d dropped to a paltry 0.05.

Some researchers argued that these statistical corrections do not discount that there was an effect in the first place. “[An effect size of 0.22] shows small exercise-related benefits on cognition,” wrote Gill Livingston, University College London. Others noted that the effect size of 0.22 reflects the heterogeneity in the trial methods and outcomes, and as such could be taken to mean that exercise benefits many cognitive domains, in people of various ages, engaged in different types and frequencies of physical activities.

In that vein, Laura Baker of Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, cautioned that meta-analyses must compare apples to apples. “This [giant meta-analysis] combined trials with so many differences then treated them all as if they were the same that I worry we are making generalizations,” she told Alzforum.

To address these shortcomings, Baker called for harmonizing methods and outcome measures in exercise-cognition trials. “Without harmonization, this type of meta-analysis does not help us in the clinic to know what to recommend,” she said. Large exercise and lifestyle intervention trials involving older adults with MCI, notably the U.S. POINTER and EXERT studies, are embracing this concept, using very similar exercise protocols, cognitive tests, and outcome measures (Aug 2022 conference news). —Chelsea Weidman Burke

References

News Citations

- Lancet Commission’s Dementia Hit List Adds Alcohol, Pollution, TBI

- In the U.S., 40 Percent of All-Cause Dementia Is Preventable

- Can Exercise Protect People Whose Plasma Tau Is Up?

- Dementia: Frailty Hastens It, Physical Activity Wards It Off

- Lifestyle Interventions May Fend Off Decline; Social Contact Helps

Further Reading

Primary Papers

- Ciria LF, Román-Caballero R, Vadillo MA, Holgado D, Luque-Casado A, Perakakis P, Sanabria D. An umbrella review of randomized control trials on the effects of physical exercise on cognition. Nat Hum Behav. 2023 Mar 27; PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

Columbia University

Biostat, Inc.

This paper focuses on the mean effect size across many meta-analyses. The authors argue that the mean is small (around 0.25). Additionally, they argue that this mean is actually incorrect. If the mean is adjusted to account for various errors, the corrected mean could be as low as zero. They conclude that “… the available causal evidence from RCTs on the exercise–cognition link is far from conclusive.”

However, the approach used in this paper does not take into account the variability in effect sizes across studies. The data presented here indicate that there is a lot of variability in effect sizes; with some meta-analyses reporting effects approaching 0.5. Again, this refers to the means, suggesting that there are studies where effect sizes are even larger than that.…More

Given this dispersion, it would be important to identify factors in studies that are associated with larger versus smaller effect sizes. The paper does make that point when it discusses pluses and minuses of various studies. These include whether or not baseline cognition was considered, the type and extent of the exercise intervention, and the nature of the control conditions. Notably, the authors “discover” the fact that each analysis reflects one “slice” of the larger universe. This should have led them to rethink their basic idea of focusing on the mean, but it did not.

There are other technical issues that could be addressed. For example, the authors attempt to correct for publication bias. There are alternate ways to address this issue that would be more appropriate, considering that the quality of studies must be taken into account.

From my point of view, there are many excellent studies, implemented in the most careful way, that have shown strong effects of exercise on cognition. So overall, I do not find this study convincing in arguing that there is minimal effect of exercise on cognition.

We published an exercise study that was not included in any of these meta-analyses. It adhered to many of the better aspects of study design mentioned in this paper. We found a strong effect of exercise on cognition (Stern et al., 2019).

References:

Stern Y, MacKay-Brandt A, Lee S, McKinley P, McIntyre K, Razlighi Q, Agarunov E, Bartels M, Sloan RP. Effect of aerobic exercise on cognition in younger adults: A randomized clinical trial. Neurology. 2019 Feb 26;92(9):e905-e916. Epub 2019 Jan 30 PubMed.

University of British Columbia

The finding of a small exercise-related benefit (d=0.22) on cognitive function is not new. This has been reported in prior systematic reviews and meta-analysis, including those by Falck and Northey (Falck et al., 2019; Northey et al., 2018). Despite the small effect size—engaging in exercise (or not) is within someone’s control. The choice to exercise directly combats physical inactivity, which is a key and modifiable risk factor for dementia as highlighted by the Lancet 2020 report (Livingston et al., 2020). By reducing physical inactivity (via engagement in exercise or physical activity)—one can reduce dementia risk by 2 percent. We know regular physical activity and exercise also impact one’s risk for obesity, hypertension, and diabetes—and thus, potentially reducing dementia risk by another 4 percent.…More

One key aspect we also need to remember is that exercise trials (randomized controlled trials) typically run for three to 12 months. This is a very short period within a person’s lifespan. Thus, should we expect a very large effect (i.e., d > .7) on cognitive function among otherwise healthy individuals? However, long-term adoption of positive lifestyle behaviors, such as regular exercise, can significantly impact one’s overall cognitive trajectory. Many epidemiological studies have shown this—those who are more physically active have reduced dementia risk.

In regard to the critique that “most meta-analyses have not included most of the available studies which would meet their inclusion criteria”—one needs to be careful. A systematic review (SR), by definition, involves a detailed and comprehensive plan and search strategy, derived a priori, with the goal of reducing bias by identifying, appraising, and synthesizing all relevant studies on a particular topic. The specific research question(s) being asked by the SR and meta-analysis dictates what papers will be included. Thus, it is very possible that one SR and meta-analysis in the broader area of exercise and cognitive function may not include the same exact set of studies as another because of differences in specific details/questions. For example, for an exercise trial to be included in the SR and meta-analysis Ryan Falck in my lab did, the trial must have included both physical and cognitive outcomes. For a study to be included in the SR and meta-analysis we did led by Cindy Barha, the studies must have included information on the breakdown of female vs. male participants (Barha et al., 2017).

References:

Falck RS, Davis JC, Best JR, Crockett RA, Liu-Ambrose T. Impact of exercise training on physical and cognitive function among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurobiol Aging. 2019 Jul;79:119-130. Epub 2019 Mar 26 PubMed.

Northey JM, Cherbuin N, Pumpa KL, Smee DJ, Rattray B. Exercise interventions for cognitive function in adults older than 50: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Feb;52(3):154-160. Epub 2017 Apr 24 PubMed.

Barha CK, Davis JC, Falck RS, Nagamatsu LS, Liu-Ambrose T. Sex differences in exercise efficacy to improve cognition: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in older humans. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2017 Jul;46:71-85. Epub 2017 Apr 22 PubMed.

UCL

This study shows small exercise-related benefits on cognition. The full model found effects size = 0.22. They looked for publication bias using three methods and this reduced effect size but the finding was still positive.

In the 2020 Lancet Commission report we previously discussed the complexity of the link between physical activity and dementia. Physical activity changes over a person’s lifetime, decreasing when someone becomes ill, varying across cultures and socioeconomic class and between genders, making it difficult to be clear, but the balance of evidence is that the link between exercise and dementia is bidirectional. Exercise might also be required to be sustained and continue nearer the time of risk to be effective.…More

I do not think there is anything contradictory in these findings. While not discussed in this interesting paper, RCTs tend by their nature to be short and recruit people who are highly motivated and knowledgeable—and both groups may change their behavior knowing there is an intervention. A recent RCT, which the authors quoted here as a high-quality exception, had, with 945 participants, high power (Zotcheva et al., 2022). Interestingly, at five years, 96 percent of controls followed national guidelines for exercise, which was up from 87 percent at baseline. It is difficult to show much effect if the control group are highly motivated exercisers.

References:

Zotcheva E, Håberg AK, Wisløff U, Salvesen Ø, Selbæk G, Stensvold D, Ernstsen L. Effects of 5 Years Aerobic Exercise on Cognition in Older Adults: The Generation 100 Study: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Sports Med. 2022 Jul;52(7):1689-1699. Epub 2021 Dec 8 PubMed.

Rush Medical College

This study examined the relationship between exercise and cognition by conducting an umbrella review of 24 meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Trial participants were of varying age and generally healthy.

The authors indicate that this relationship may not be as established as we think. They point to the importance of replicating findings in the area of exercise and cognition.

Interestingly, the authors found that few studies were the same across more than one meta-analysis. Meta-analyses may have missed including eligible studies slightly under 50 percent of the time. They also varied in terms of analytical approaches and methods.

Overall, I think the authors should be commended for addressing publication bias in great detail.…More

It may be worth noting that an established model does not exist to describe the mechanisms behind the relationship between exercise and cognition.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.