Brain Atrophy Patterns Support Distinct Subtypes of Frontotemporal Dementia

Quick Links

Frontotemporal dementia presents a thorny thicket for researchers to pick their way through. Symptoms range from sluggish apathy to obsessive compulsion, and numerous genetic mutations and neuropathologies can underlie each person’s disease. Variation in behavioral symptoms may be explained by degeneration of specific neural networks, according to a study published in the July 18 JAMA Neurology. Researchers led by Bruce Miller at the University of California, San Francisco, reported that some atypical social behaviors—including recklessness and failure to pick up on common social cues—correlated with specific patterns of neurodegeneration in two different neural networks in the brain, while other behaviors showed no such relation. “In an elegant way, this paper highlights that bvFTD is not a unified syndrome, and that a major determinant of clinical differences is anatomy, rather than genetic mutation or pathology,” commented Marek-Marsel Mesulam of Northwestern University in Chicago, who was not involved in the study.

People with behavioral variant FTD present with a dizzying array of cognitive and behavioral symptoms, including executive dysfunction, lack of inhibition, severe apathy, loss of empathy, obsessive-compulsive tendencies, and problems reading social cues. The disorder can be sporadic, or caused by mutations in C9ORF72, tau, progranulin, and other, as yet unknown genes. Neurons in people with mutations in C9ORF72 or progranulin accumulate various types of TDP-43 inclusions, while people with tau mutations have tau tangles (see Karageorgiou and Miller, 2014).

The regions of the brain affected by the disease vary significantly as well. Multiple imaging studies have identified various patterns of atrophy, white-matter damage, and waning neural activity among bvFTD patients. A 2009 study described four distinct patterns of regional atrophy, each with varying levels of gray-matter loss in the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes, suggesting subtypes of the disease (see Whitwell et al., 2009). To some degree, researchers could match these different anatomical subtypes to specific clinical symptoms. For example, people with atrophy primarily in the frontal lobe struggled with executive function, while those with a predominantly temporal loss did poorly in memory tests.

In an effort to more clearly distinguish between disease subtypes, first author Kamalini Ranasinghe and colleagues sliced the anatomical pie in a different way. Because neurodegenerative diseases, including frontotemporal dementia, attack along neural networks in the brain, they reasoned that the heterogeneity in bvFTD symptoms might be explained by dysfunction in certain networks. Specifically, the researchers looked for atrophy in regions belonging to either the salience or semantic appraisal networks, because these are believed to be affected by the disease. The salience network (SN) calls on the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex and frontoinsula as major hubs, which together interpret external information (like a dog snarling) and internal information (the feeling of a cold sweat), and motivate a person into action depending on the significance (or salience) of those signals. The closely associated semantic appraisal network (SAN) includes the temporal pole, ventral striatum, subgenual cingulate, and basloateral amygdala, which together decipher the meanings of social stimuli within a given context. This network holds most of us back from laughing at a funeral, or making inappropriate remarks (see Seeley et al., 2011).

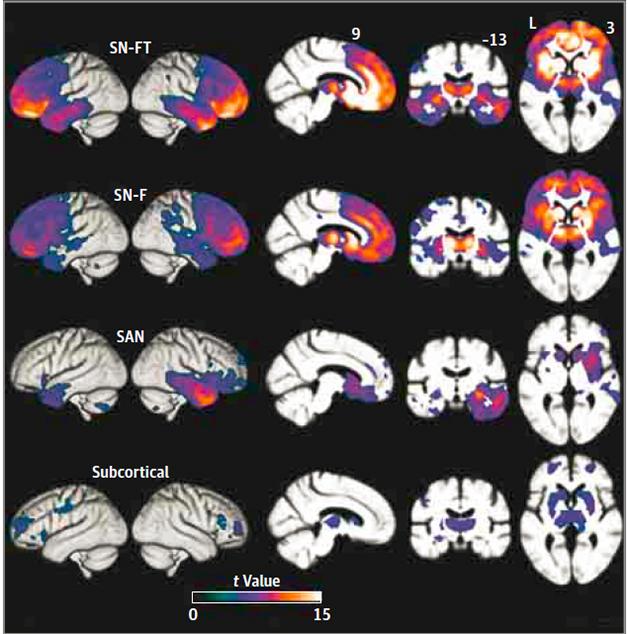

Variants of a Variant. Four distinct atrophy patterns occurred in people with bvFTD, each with differing involvement of the frontal, temporal, and subcortical regions of the SN and SAN networks. [Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.]

To look for those changes in these networks, the researchers analyzed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of 90 bvFTD patients. They compared gray-matter volume in 18 regions of the brain with those in age-matched controls to estimate levels of atrophy, and used principle component analysis, a statistical tool that can pull out distinctive variations within a dataset, to identify four groups of patients with specific atrophy patterns. Two groups, which the researchers labelled SN-F and SN-FT, displayed marked gray-matter loss within salience network structures. Frontal, but not temporal, regions appeared relatively shrunken in the 27 patients in the SN-F group, while the 21 patients in the SN-FT group lost volume in both frontal and temporal SN structures. The SAN was hit hardest in a third group of just eight patients, whose atrophy was confined to the right side of the brain. While cortical and subcortical regions took a hit in both of the SN groups, only the cortex was significantly affected in the SAN group. A fourth group, consisting of 30 patients, surprised the researchers. Only subcortical regions appeared to have withered, with cortices remaining relatively unscathed.

The researchers next looked to see if these atrophy patterns correlated with any genetic, pathological, or symptomatic characteristics of the disease. Fourteen patients carried the C9ORF72 gene expansion and some were found in each group; four MAPT mutation carriers split between the SN-FT and SAN groups; and six GRN mutation carriers were spread among the SN-F, SAN, and subcortical groups. Autopsy of 24 patients revealed similar proteinopathy heterogeneity. People with tau and TDP-43 pathology were represented in the SN-F, SN-FT, and SAN subgroups. Five of six patients in the subcortical group had TDP-43 inclusions, while the remaining patient was found to have tau pathology consistent with argyrophilic grain disease, not FTD.

Further differences among the groups emerged when the researchers measured patients’ neuropsychological, cognitive, and socioemotional abilities. While the core bvFTD symptoms—lack of inhibition, apathy, loss of empathy, obsessive behavior, mouthing inappropriate objects (hyperorality in clinical parlance), and poor performance on neuropsychological tests such as memory and executive function—occurred in all subgroups, there was some segregation. People in the SN-F group performed worse than others on tests of executive function, while memory problems were most frequent in the SN-FT group.

All of the patients in the SAN group lacked inhibition, while all of the people in the SN-FT group obsessed with hyperorality. People in the SAN group retained their sense of empathy and warmth better than others, but failed to recognize sarcasm. Katherine Rankin of UCSF, one of the study’s authors, said the latter aligns with a breakdown in the SAN, which would prevent people from detecting subtle voice or facial changes indicative of sarcasm. A breakdown in the SAN would also make a person act inappropriately in social situations, as they might fail to pick up on key social cues, such as a somber mood.

The researchers found no significant differences between the groups in terms of disease duration, age at evaluation, or depression. However, people in the subcortical group progressed much more slowly than any other group. The researchers speculated that the people in this subcortical group could often be labeled as “bvFTD phenocopies,” who are thought to have not bvFTD but some other disease that mimics some of the symptoms. However, the authors believe they have bvFTD because their symptoms were typical of the disease, 30 percent had an FTD mutation, and all six of those autopsied had confirmed bvFTD by pathology. Misdiagnosis is a common problem in the FTD field, because many of the behavioral problems associated with bvFTD are shared with people who have psychiatric illnesses and neurodegenerative disease is sometimes ruled out in people whose symptoms appear stable (see Kipps et al., 2010).

How could patients with subcortical atrophy have similar bvFTD symptoms to people with predominantly cortical neurodegeneration? “These subcortical bvFTD patients likely have a disconnect syndrome, in which connections between the subcortical and cortical regions are lost,” explained Rankin. “That could be why their symptoms are largely the same as patients with cortical damage.”

Mesulam pointed out that subcortical degeneration, particularly in the thalamus, has been reported before in people with seemingly frontal lobe-associated symptoms. Indeed, 25 years ago he and colleagues published a paper describing a patient with a frontal-lobe syndrome who was found to have lesions in the dorsolateral nucleus of the thalamus (see Sandson et al., 1991). As this region of the thalamus connects with the frontal lobes, it would make sense that the patient appeared to have frontal degeneration, Mesulam said. The findings highlight the importance of considering connections between regions, rather than looking at each region in isolation, he added.

Rankin added that the subcortical group is the only one that may allow researchers to predict underlying pathology, because most of the autopsied patients had TDP-43 aggregates.

“The identification of a significant subset (36 percent) of bvFTD patients with primarily subcortical atrophy is a potentially important finding which needs replication,” commented Ian McKeith of Newcastle University in England. “Not only may it be important for prognostication (slow progression) but might also help stratify patients for trials of putative disease modifying agents.”

Despite the potential usefulness of the subcortical group, the other three groups were a mixed bag of pathology and mutations. This was a disappointment to David Mann of the University of Manchester in England. “While it is clear that other forms of FTLD such as semantic dementia, bvFTD with motor neuron disease, and primary progressive non-fluent aphasia show tight histological or genetic linkages, this unfortunately is not the case for bvFTD, and histological predictions for this particular FTLD subgroup, employing ‘biomarker analysis,’ remain elusive,” he wrote to Alzforum.

Mesulam was not surprised at the lack of tight categorization between the subgroups. “The lesson to be learned here is that diseases don’t occur in a vacuum; they occur in people who bring in very individualized peculiarities of their brain organization.”—Jessica Shugart

References

Paper Citations

- Karageorgiou E, Miller BL. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a clinical approach. Semin Neurol. 2014 Apr;34(2):189-201. Epub 2014 Jun 25 PubMed.

- Whitwell JL, Przybelski SA, Weigand SD, Ivnik RJ, Vemuri P, Gunter JL, Senjem ML, Shiung MM, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, Parisi JE, Dickson DW, Petersen RC, Jack CR, Josephs KA. Distinct anatomical subtypes of the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia: a cluster analysis study. Brain. 2009 Nov;132(Pt 11):2932-46. PubMed.

- Seeley WW, Zhou J, Kim EJ. Frontotemporal Dementia: What Can the Behavioral Variant Teach Us about Human Brain Organization?. Neuroscientist. 2011 Jun 13; PubMed.

- Kipps CM, Hodges JR, Hornberger M. Nonprogressive behavioural frontotemporal dementia: recent developments and clinical implications of the 'bvFTD phenocopy syndrome'. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010 Dec;23(6):628-32. PubMed.

Other Citations

Further Reading

Papers

- Landin-Romero R, Kumfor F, Leyton CE, Irish M, Hodges JR, Piguet O. Disease-specific patterns of cortical and subcortical degeneration in a longitudinal study of Alzheimer's disease and behavioural-variant frontotemporal dementia. Neuroimage. 2016 Mar 21; PubMed.

Primary Papers

- Ranasinghe KG, Rankin KP, Pressman PS, Perry DC, Lobach IV, Seeley WW, Coppola G, Karydas AM, Grinberg LT, Shany-Ur T, Lee SE, Rabinovici GD, Rosen HJ, Gorno-Tempini ML, Boxer AL, Miller ZA, Chiong W, DeMay M, Kramer JH, Possin KL, Sturm VE, Bettcher BM, Neylan M, Zackey DD, Nguyen LA, Ketelle R, Block N, Wu TQ, Dallich A, Russek N, Caplan A, Geschwind DH, Vossel KA, Miller BL. Distinct Subtypes of Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia Based on Patterns of Network Degeneration. JAMA Neurol. 2016 Sep 1;73(9):1078-88. PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

University of Manchester

This is an interesting study using principal component analysis (PCA) on 18 regions of interest data derived from MRI scans of 90 patients meeting FTD Consortium consensus criteria for bvFTD. From this analysis four clusters were derived, each conforming to a particular anatomical pattern of atrophy. A differential involvement of salience and semantic appraisal networks in the patterns of atrophy formed the basis for characterizing these subgroups. However, given that the bvFTD group comprised patients with a multiplicity of underlying disorders, ranging from pure cortical degenerations like Pick’s disease to cortico-subcortical degenerations such as corticobasal degeneration, it is not altogether surprising that different atrophy patterns would emerge from PCA.…More

However, what would have been really interesting, and important, about the study would have come from the neuropathological and genetic correlations, had any of the four subgroups predicted underlying histology or associated with any one genetic mutation. In this way, underlying disease mechanics might have been predicted in bvFTD in life with obvious therapeutic value. Instead, mutations such as C9ORF72 expansions were spread across all four subgroups, and tau and TDP-43 histologies were similarly represented within each subgroup. While it is clear that other forms of FTLD such as semantic dementia, bvFTD with motor neurone disease, and primary progressive non-fluent aphasia show tight histological or genetic linkages, this unfortunately is not the case for bvFTD, and histological predictions for this particular FTLD subgroup, employing “biomarker analysis,” remain elusive. Unfortunately, this much-needed added value to the study was not forthcoming.

Newcastle University,

This paper is carefully modest in its claims, as one would expect from this very expert group of clinical researchers who understand well the complexities of FTD. The identification of a significant subset (36 percent) of bvFTD patients with primarily subcortical atrophy is a potentially important finding that needs replication. Not only may it be important for prognostication (slow progression), it might also help stratify patients for trials of putative disease-modifying agents. We may try this approach on our Lewy body dementia patients who also show considerable phenotypic variation, which we believe to be at least in part due to different neuroanatomic lesion patterns.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.