In Aging, Epigenetic Wet Blanket Douses Mitochondria

Quick Links

What’s the point of living longer if you spend your extra years in poor health? A new study published February 26 in Nature discovered that reining in the expression of two epigenetic regulators could extend the “healthspan”—as opposed to merely the lifespan—of worms and mice. Led by Lubin Jiang and Shi-Qing Cai at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Shanghai, the scientists studied BAZ-2 and SET-6, proteins that read and write epigenetic signals, respectively. They found that levels of both proteins ramp up with age in both species, in turn dampening expression of genes involved in mitochondrial function. The resulting metabolic slowdown put worms off their food and they mated less, and it hastened memory loss in old mice. What about orthologs of these epigenetic proteins in humans? Their levels increased in the brain with age, and correlated with progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

- Epigenetic regulators increase in aging worms.

- BAZ2 and SET6 suppress mitochondrial gene expression.

- They accelerate memory loss in mice, correlate with AD progression.

The study reinforces current thinking that mitochondria are key to aging, noted Russell Swerdlow of Kansas University Medical Center in Kansas City. “The suggestion emerges that brain aging and AD are mechanistically linked, that AD may represent exaggerated brain aging, and that mitochondria are at the heart of both processes,” Swerdlow wrote to Alzforum.

Human life expectancy has increased in recent decades, but this extended lifespan often translates into a longer time in a frail and sickly state (Beard et al., 2016; Hansen and Kennedy, 2016). In worms, lifespan can be extended through caloric restriction, yet these gains also come at a cost to health (Bansal et al., 2015).

One factor that limits healthspan in nematodes is an age-related drop in BAS-1, an enzyme that helps synthesize both dopamine and serotonin (Yin et al., 2014). Short supply of these neurotransmitters causes problems for worms—most notably, a weakening of the pharyngeal pumping by which they slurp in liquid and extract bacteria from it for food. In older people, waning production of dopamine has also been tied to cognitive decline (Bäckman et al., 2006).

Using the characteristic drop in BAS-1 as a marker of declining health with age, co-first authors Jie Yuan, Si-Yuan Chang, Shi-Gang Yin, Zhi-Yang Liu, and Xiu Cheng searched for modifiers of lifespan and healthspan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Using a knockdown screen, they pulled out 59 hits that contributed to decline in BAS-1 expression with age. Knocking down many of these genes strengthened pharyngeal pumping in aging worms, and 10 of them had human homologs implicated in neurodegeneration or cell senescence.

The two most prominent hits—BAZ-2 and SET-6—are sides of the same epigenetic coin. SET-6 is an “epigenetic writer,” a putative histone3/lysine9 (H3K9) methyltransferase. BAZ-2 is a putative “epigenetic reader,” i.e., it recognizes modified histones and recruits transcriptional regulators.

Both proteins are expressed in the nucleus, but it was unclear what they do there. Yuan and colleagues found that deletion of BAZ-2 and/or SET-6 not only extended lifespan, but enhanced pharyngeal pumping and mating in aged worms. Nematodes devoid of these epigenetic regulators were of a tougher stock and better withstood environmental insults including heat shock, ultraviolet exposure, and hydrogen peroxide.

How do BAZ-2 and SET-6 hasten aging? The researchers found that the two proteins together bind to promoter regions of more than 2,000 genes, dampening their expression via histone methylation. Among these target genes were numerous nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes. Through their repression of these genes, BAZ-2 and SET-6 sapped oxygen consumption and ATP production, and bungled critical stress responses that maintain mitochondrial proteostasis.

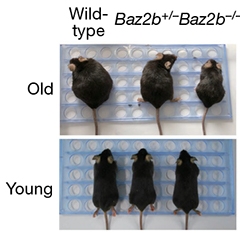

Old Whippersnappers? While wild-type mice grew fat with age, animals lacking both copies of the epigenetic reader Baz2b stayed trim, indicating improved mitochondrial function. [Courtesy of Yuan et al., Nature, 2020.]

The researchers extended their nematode findings to mammals, reporting that orthologs of BAZ-2 and SET-6 dampened expression of key mitochondrial genes in cultured mouse and human cells. Knocking out BAZ-2 in mice assuaged age-related decline in brain metabolism, weight gain, and spatial memory loss, but did not extend lifespan.

Next, the researchers accessed a gene-expression dataset of human prefrontal cortex samples from the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center, including 376 from people with late-onset AD and 173 from nondemented elderly (Zhang et al., 2013). Among the samples from cognitively normal people, levels of human homologs of BAZ-2 and SET-6 increased with age. Among those with AD, the proteins correlated with AD progression, and with reduced expression of mitochondrial genes.

The findings suggest that epigenetic changes could underlie pathological relationships between aging, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neurodegenerative disease, the authors proposed.

“The study raises many questions, the most important one being what lies upstream of, and triggers, the BAZ-2 and SET-6 age-related changes,” Swerdlow wrote. “Specifically, one has to wonder if BAZ-2 and SET-6 are mediating an age-related physiologic adaptation, versus driving aging itself. Either way, it will be interesting to see where these findings go, in both the aging and AD fields.”

Cai told Alzforum that his lab is investigating the mechanisms that drive the epigenetic changes, and how they relate to unhealthy aging and disease. He is also hunting for small molecules that target the epigenetic regulators.—Jessica Shugart

References

Paper Citations

- Beard JR, Officer A, de Carvalho IA, Sadana R, Pot AM, Michel JP, Lloyd-Sherlock P, Epping-Jordan JE, Peeters GM, Mahanani WR, Thiyagarajan JA, Chatterji S. The World report on ageing and health: a policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet. 2016 May 21;387(10033):2145-2154. Epub 2015 Oct 29 PubMed.

- Hansen M, Kennedy BK. Does Longer Lifespan Mean Longer Healthspan?. Trends Cell Biol. 2016 Aug;26(8):565-568. Epub 2016 May 27 PubMed.

- Bansal A, Zhu LJ, Yen K, Tissenbaum HA. Uncoupling lifespan and healthspan in Caenorhabditis elegans longevity mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Jan 5; PubMed.

- Yin JA, Liu XJ, Yuan J, Jiang J, Cai SQ. Longevity manipulations differentially affect serotonin/dopamine level and behavioral deterioration in aging Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2014 Mar 12;34(11):3947-58. PubMed.

- Bäckman L, Nyberg L, Lindenberger U, Li SC, Farde L. The correlative triad among aging, dopamine, and cognition: current status and future prospects. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30(6):791-807. Epub 2006 Aug 9 PubMed.

- Zhang B, Gaiteri C, Bodea LG, Wang Z, McElwee J, Podtelezhnikov AA, Zhang C, Xie T, Tran L, Dobrin R, Fluder E, Clurman B, Melquist S, Narayanan M, Suver C, Shah H, Mahajan M, Gillis T, Mysore J, MacDonald ME, Lamb JR, Bennett DA, Molony C, Stone DJ, Gudnason V, Myers AJ, Schadt EE, Neumann H, Zhu J, Emilsson V. Integrated systems approach identifies genetic nodes and networks in late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Cell. 2013 Apr 25;153(3):707-20. PubMed.

Further Reading

Papers

- Yin JA, Gao G, Liu XJ, Hao ZQ, Li K, Kang XL, Li H, Shan YH, Hu WL, Li HP, Cai SQ. Genetic variation in glia-neuron signalling modulates ageing rate. Nature. 2017 Nov 8;551(7679):198-203. PubMed.

Primary Papers

- Yuan J, Chang SY, Yin SG, Liu ZY, Cheng X, Liu XJ, Jiang Q, Gao G, Lin DY, Kang XL, Ye SW, Chen Z, Yin JA, Hao P, Jiang L, Cai SQ. Two conserved epigenetic regulators prevent healthy ageing. Nature. 2020 Mar;579(7797):118-122. Epub 2020 Feb 26 PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

Quietmind Foundation

While the hunt continues for "small molecule regulators," the use of indirect transcranial and intraocular and intranasal near-infrared photobiomodulation can be used to mitigate cell death and improve ATP production and cortical blood flow. When this type of therapy is combined with brainwave biofeedback training to normalize neural connectivity, it is possible to significantly modify both behavioral and cognitive symptoms associated with both aging and neurodegenerative disease. This is being borne out in our current trials in collaboration with Baylor Research Institute and in our clinical practice in Philadelphia.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.