Quick-and-Early IVIG Therapy: Hints of Promise?

Quick Links

If another small, hopeful trial is to be believed, pooled antibody treatment has the potential to stave off dementia. Eight weeks of treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), given to mildly symptomatic people deemed on the road to an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, just might slow the disease course. At least, the therapy slows shrinkage of the brain, according to preliminary results presented at the American Academy of Neurology meeting, held 16-23 March 2013 in San Diego, California. Following on other small Phase 2 studies that suggested a different intravenous immunoglobulin product could be beneficial for Alzheimer’s, Shawn Kile of the Sutter Neuroscience Institute in Sacramento, California, is trying this type of treatment in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). He hopes a short, early course of IVIG could delay Alzheimer’s dementia, although much further study will be necessary to confirm his hunch.

Doctors routinely use IVIG to treat a variety of infectious, immunological, and inflammatory conditions. The medicine is made from pooled plasma antibodies from donors, and among those antibodies are some that bind Aβ. People with Alzheimer’s possess unusually low levels of Aβ antibodies. IVIG is thought to work by promoting amyloid clearance and through its general anti-inflammatory effects. A previous Phase 2 study, led by Norman Relkin of Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City, suggested it could slow cognitive decline and brain atrophy (see ARF related news story), and several clinical trials are underway.

However, IVIG’s possible benefits come with a major potential caveat: The medication is expensive and in short supply, since it relies on donated plasma. If the treatment worked, Kile said, there would not be nearly enough of it to go around. In his study, therefore, he tried a shorter treatment course than others who have provided IVIG for 18 months or more to people who already have AD. Kile believed an early, brief therapy might suffice because in a previous study, scientists found that people who received IVIG treatment for reasons unrelated to AD were less likely to develop Alzheimer’s later (Fillit et al., 2009).

In Kile’s ongoing study, 52 people with MCI were evenly split between IVIG or saline placebo, receiving five doses spaced two weeks apart. Octapharma donated the IVIG but did not directly conduct the study. Kile used a dose of 0.4 gram IVIG per kilogram of body weight at each visit, based on the optimal dose from the earlier Phase 2 study led by Relkin. The total IVIG amount provided over the eight-week course matches standard dosage for IVIG treatment of neurological conditions such as the autoimmune condition Guillain-Barre syndrome, Kile said. He plans to follow the participants for two years. Thus far, 28 participants have hit the one-year mark, and Kile reported preliminary findings from that group in a poster at the meeting.

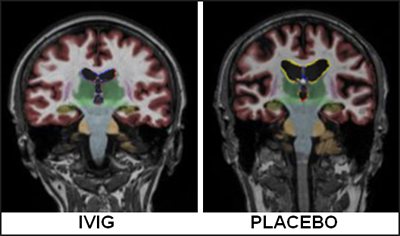

Comparing magnetic resonance images obtained at baseline and one year into the study, Kile observed that, while the placebo group lost an average of 8.8 percent volume, those on IVIG lost 5.7 percent, and the difference was statistically significant. “I was surprised; with a small ‘n’ we were able to show that,” Kile commented. Standard cognitive test scores changed little from baseline over the year. Based on the brain changes, Kile anticipates that cognitive decline may be noticeably slower in the treated group after more time has passed. This is at odds with immunotherapy results, where treated patients showed more atrophy than those on placebo, but it jibes with data from an MCI trial of B vitamins, which reported less atrophy in the treated group (Smith et al., 2010).

Magnetic resonance imaging showed that one year after treatment, people treated with IVIG (left) had less brain shrinkage than those on placebo (right). Image courtesy of Shawn Kile, Sutter Neuroscience Institute, Sacramento, California

The results confirm those of his earlier Phase 2 study, Relkin commented in an e-mail to Alzforum, although with a smaller effect on brain size. “If their final results prove to be consistent with these interim findings, it will likely spark a lively discussion about whether a short duration of IVIG is sufficient to obtain a meaningful therapeutic response in very mildly affected dementia patients,” he wrote. “A much larger study will be needed to draw firm conclusions about the use of IVIG in MCI.” (See full comment below.)

It is far too early to draw conclusions from Kile’s data, agreed Richard Dodel of Philipps University in Marburg, Germany, who has also worked with Octapharma’s IVIG (see ARF related news story on Dodel et al., 2013). He was skeptical that the final results would be positive. “This would be too good to be true,” Dodel put it. He also noted that change in brain volume is not a validated biomarker for AD, and it is not clear how that atrophy, or lack thereof, would affect thinking. “The cognitive measures are the most important measures at the moment,” Dodel said.

Kile’s group just completed dosing their last enrollee. As the study proceeds, he plans to analyze the rate at which people progress from MCI to full-blown AD.

Separately, researchers are also awaiting the results of a Phase 3 study of Baxter BioScience’s Gammagard® IVIG.—Amber Dance.

References

News Citations

- Toronto: In Small Trial, IVIg Slows Brain Shrinkage

- Research Brief: Octapharma IVIg Iffy in Phase 2 Trial

Paper Citations

- Fillit H, Hess G, Hill J, Bonnet P, Toso C. IV immunoglobulin is associated with a reduced risk of Alzheimer disease and related disorders. Neurology. 2009 Jul 21;73(3):180-5. PubMed.

- Smith AD, Smith SM, de Jager CA, Whitbread P, Johnston C, Agacinski G, Oulhaj A, Bradley KM, Jacoby R, Refsum H. Homocysteine-lowering by B vitamins slows the rate of accelerated brain atrophy in mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2010;5(9):e12244. PubMed.

- Dodel R, Rominger A, Bartenstein P, Barkhof F, Blennow K, Förster S, Winter Y, Bach JP, Popp J, Alferink J, Wiltfang J, Buerger K, Otto M, Antuono P, Jacoby M, Richter R, Stevens J, Melamed I, Goldstein J, Haag S, Wietek S, Farlow M, Jessen F. Intravenous immunoglobulin for treatment of mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding trial. Lancet Neurol. 2013 Mar;12(3):233-43. Epub 2013 Jan 31 PubMed.

External Citations

Further Reading

Papers

- Shayan G, Adamiak B, Relkin NR, Lee KH. Longitudinal analysis of novel Alzheimer's disease proteomic cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers during intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. Electrophoresis. 2012 Jul;33(13):1975-9. PubMed.

- Relkin NR, Szabo P, Adamiak B, Burgut T, Monthe C, Lent RW, Younkin S, Younkin L, Schiff R, Weksler ME. 18-Month study of intravenous immunoglobulin for treatment of mild Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2009 Nov;30(11):1728-36. PubMed.

- Dodel RC, Du Y, Depboylu C, Hampel H, Frölich L, Haag A, Hemmeter U, Paulsen S, Teipel SJ, Brettschneider S, Spottke A, Nölker C, Möller HJ, Wei X, Farlow M, Sommer N, Oertel WH. Intravenous immunoglobulins containing antibodies against beta-amyloid for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004 Oct;75(10):1472-4. PubMed.

News

- Toronto: In Small Trial, IVIg Slows Brain Shrinkage

- Research Brief: Octapharma IVIg Iffy in Phase 2 Trial

- Zuers—Meeting Mixes Translational News and Debate

- Paris: More Trial News, Mixed at Best

- Chicago: More Phase 2 News—PBT2 and IVIg

- Madrid: Pooled Antibody Cocktail, New Metal Quencher

- Pilot Study Shows Promise of Passive Immunotherapy

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

Weill Medical College of Cornell University

First off, I’d like to disclose that I am lead investigator in the GAP 160701 Study, which is the NIA- and Baxter-supported Phase 3 pivotal study of Gammagard® IVIG in AD that has been conducted at 45 ADCS sites in the U.S. and Canada. It employed a placebo-controlled, double-blind randomized design in which infusions of either IVIG or placebo were administered every two weeks for 18 months to 390 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Results will be announced in the second quarter of 2013.

The interim results presented by Dr. Kile and colleagues at the 2013 AAN meeting are encouraging, albeit preliminary. I am particularly gratified to see an independent replication of the finding I first reported at the AAN meeting in 2010 of a significantly reduced rate of brain atrophy following IVIG treatment of Alzheimer's patients. The current study used the same dose of IVIG (0.4 g/kg every two weeks) for each infusion that we found worked best in our Phase 1 and 2 studies of IVIG in Alzheimer's patients, but they gave fewer infusions. The magnitude of the effect they observed on brain appears to be commensurately smaller than what we observed. Nevertheless, if their final results prove to be consistent with these interim findings, it will likely spark a lively discussion about whether a short duration of IVIG is sufficient to obtain a meaningful therapeutic response in very mildly affected dementia patients. This is an important consideration because IVIG is costly and supplies are limited.

MCI patients are by definition more mildly affected than persons with actual dementia due to Alzheimer’s, so studies of MCI typically require larger numbers of subjects and longer periods of observation. Dr. Kile and his colleagues took a calculated risk in studying only 51 subjects and using a very short exposure to IVIG, both of which might be expected to reduce the likelihood of a successful study outcome. A much larger study will be needed to draw firm conclusions about the use of IVIG in MCI.

In the meantime, it’s important to point out that IVIG is not approved for use in treating MCI or AD at this time.

Quietmind Foundation

The clinical study of using IVIG in MCI as reported above by Kile is encouraging to those supporters of the "emerging role of pathogens in Alzheimer’s disease." Hopefully, the larger clinical trial of IVIG, as mentioned by Norman Relkin in 390 patients, will also slow shrinkage of the brain in the treated group as compared to the controls on imaging studies.

Since IVIG uses pooled γ globulin, the treatment as mentioned will never have the resources and availability that a treatment engineered by biotech or big pharmacological companies. Such companies could narrow down the therapeutic response to more defined molecules such as TNFα, interleukins, macrophage inhibition, etc. Eventually, then, antiviral, antibiotic, and other early interventional measures will be implemented before brain shrinkage due to amyloid plaques and tau tangles occurs.

However, any success now in Alzheimer's therapeutics is highly encouraged, as the economic burden to the healthcare system is out of control. The newspaper yesterday reported 15.4 million caregivers provided more than 17.5 billion hours of unpaid care valued at $216 billion for Alzheimer's patients in 2012!

Ex Medical Director, Regen Therapeutics

This result makes me wonder if there is overlap between IVIG and colostrum, because the latter contains many antibodies, and in the case of Colostrinin®, also proline-rich peptides (PRP). Researchers at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston have shown that PRP has multiple effects in models of AD pathogenesis, at biochemical and genetic levels as well as in live mice and clinical trials in humans.

References:

Szaniszlo P, German P, Hajas G, Saenz DN, Kruzel M, Boldogh I. New insights into clinical trial for Colostrinin in Alzheimer's disease. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009 Mar;13(3):235-41. PubMed.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.