Brain Banks for Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s Remain Underused

Quick Links

In the past decade, brain banks around the world have formed networks that set standards for handling and storing tissue, and combined data into inventories researchers can search for what they need (see Part 2 of this series, and Alzforum listing of consortia and brain banks). The Alzheimer’s field boasts one of the largest such networks of banked brains. The National Institute on Aging (NIA) in Bethesda, Maryland, currently supports 27 Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADCs), each of which has a neuropathology core. While the brains are stored locally, the ADCs have to submit all neuropathology, genetic, and clinical data to the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center in Seattle. The NACC database contains a wealth of associated longitudinal data on many thousands of samples, yet few researchers use this resource to the full, neurologists lamented to Alzforum. “I think the clinical and pathological data that comes out of the Alzheimer’s centers is superior to anything else,” said NIA’s Creighton (Tony) Phelps, who oversees the ADCs.

Pretty in Pink.

Hematoxylin and eosin stain highlights a fibrillar Aβ plaque in a frontal lobe section from an Alzheimer’s patient. [Image courtesy of Nigel Cairns, Washington University, St. Louis.]

How best to tap this resource? The NACC’s centralized database has an online query system that allows researchers to sort its contents by age, ethnicity, cognitive status, and ApoE genotype to find out which ADCs have brain samples that meet their study requirements. For researchers studying rare diseases such as corticobasal syndrome, or others who want to stratify samples by a genetic risk factor other than ApoE, NACC personnel will prepare a customized table of available tissue, said director Walter (Bud) Kukull. At the NIH Alzheimer’s Disease Research Summit last week in Bethesda, Maryland, Kukull urged the audience to make wider use of NACC, promising that its staff would respond to customized requests within a week.

Once researchers know where suitable samples reside, they request them from the local centers. All requests are granted, Kukull told Alzforum, although ADC personnel may ask scientists to modify their requirements to analyze fewer brains or look at a different brain region if the center cannot provide as much tissue as requested, especially for small areas in high demand, such as the hippocampus.

For most studies, researchers are better off obtaining all tissue from a single ADC, because each site processes and stores brains in a slightly different way, noted Peter Nelson, who directs the brain bank at the University of Kentucky ADC in Lexington. The standardization of BrainNetEurope and the NeuroBioBank (see Part 2) is not in place at the NACC. To mitigate this problem, in 2014 an NIA task force issued best practice guidelines to set minimum standards for brain banking at the ADCs. The guidelines stress the need to keep the postmortem interval short, quickly freeze tissue blocks or slices to avoid deterioration of RNA and DNA, and measure tissue integrity.

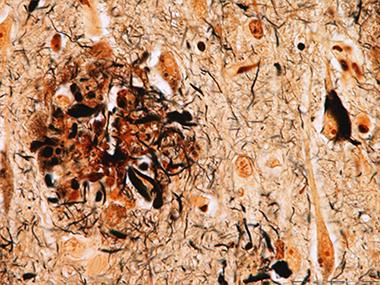

Alzheimer’s Hallmarks.

A modified Bielschowsky silver stain reveals a neuritic plaque (left) and neurofibrillary tau tangle (right). [Image courtesy of Nigel Cairns, Washington University, St. Louis.]

However, the guidelines do not spell out exact methods, because neuropathologists like to do things their way, so samples vary somewhat between centers. All centers prepare both chemically fixed and frozen brain sections, as different experiments require different preparations. For example, studies of subcellular structures must be done in fixed, embedded sections, whereas extractions and biochemical experiments need frozen tissue. Often, pathologists fix half the brain for use in teaching and neuropathological diagnosis, and section the other half into thick coronal slices that are flash-frozen for later research use (Vonsattel et al., 2008).

An Abundance of Alzheimer’s Data

The major strengths of the NACC database are its size and the amount of information available on each donated brain, said Phelps. The NACC maintains data on more than 13,000 brains donated since 1984. The old samples come with minimal data, but since 2005, every brain donation caps extensive clinical and cognitive records from yearly assessments of the volunteer. About 3,000 brains belong to this Uniform Data Set (UDS). The number continues to grow, as around 30,000 patients are currently in treatment at ADCs nationwide, and about half of them have agreed to donate their brains upon death, Kukull said.

In the NACC database, nearly all donors had a memory disorder. Postmortem, about half of the UDS brains were diagnosed with AD, another 10 percent each with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), frontotemporal dementia, or AD pathology that did not reach the diagnostic threshold, and 6 percent with vascular dementia. A handful of donors had other conditions, such as hippocampal sclerosis or prion disease. Minorities are underrepresented in this sample, making up only 6 percent.

Control brains represent the greatest limitation of the NACC database. The ADC banks contain only about 140 brains without any evident pathology. Completely healthy brains are rare because almost all older people have some degree of pathology, such as modest tau deposits in the medial temporal lobe, said Nigel Cairns of the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Washington University in St. Louis. While pristine brains are in short supply, most banks contain a larger (though still insufficient) number of brains from cognitively healthy people who had minimal pathology. These serve as controls for most studies. “From a research point of view, that is not a problem,” Cairns said.

The UDS data that accompany each brain sample comprise clinical history, neurologic exams, neuropsychological test batteries, and functional rating scales, as well as the neuropathologic diagnosis. Most brain donations also include DNA and blood samples, which are stored in a central location at the National Cell Repository for Alzheimer’s Disease at Indiana University Medical Center in Indianapolis. The NACC currently does not collect biomarker data, but researchers can request that directly from the centers. A new version of the UDS starting later this year will incorporate biomarker data, Kukull said.

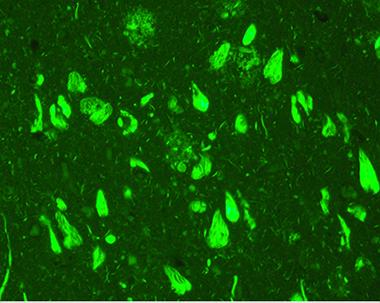

Amyloid Burden.

Thioflavin S stain lights up amyloid deposits that choke neurons and processes. [Image courtesy of Nigel Cairns, Washington University, St. Louis.]

“This highly annotated clinical and laboratory information greatly enhances the research value of a brain donation,” Thomas Montine, who directs the University of Washington ADC in Seattle, told Alzforum. Other researchers agree. “You can do amazing clinico-pathological correlations with NACC data,” Nelson said. This includes generating and testing hypotheses and analyzing genetic and environmental risk factors. “You may not even need to do a biochemical experiment, because there’s so much you can do with the data they already have on hand,” Nelson noted. As with tissue, researchers can request NACC data through an online query. NACC staff will prepare data reports, help with statistical analysis, discuss research questions, and even critique manuscripts before publication. “I think the asset is underutilized,” Nelson said.

Parkinson’s Field Builds Longitudinal Datasets

Researchers specializing in Parkinson’s disease have no such large resource as the NACC, but several smaller programs do store tissue. The Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program in Sun City, Arizona, is a place to start, noted Beth-Anne Sieber at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Like the ADCs, the program enrolls participants in a longitudinal clinical study, which at Banner includes brain and body donation at death (see Beach et al., 2008). The total collection contains more than 1,600 brains and 430 whole-body donations, which span the gamut from healthy controls to people diagnosed with Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s disease (Beach et al., 2015). NINDS supports the PD portion of the Banner program, while NIA supports the AD portion.

Deadly Dots?

Low- and high-resolution images of Marinesco bodies (purple-black) in the nuclei of dopaminergic cells in the substantia nigra. These neurons contain the natural pigment neuromelanin (brown). [Image courtesy of Thomas Beach, Sun Health Research Institute, Sun City, Arizona.]

While the number of brains with Parkinson’s disease and related disorders just passed 200, each comes with extensive data, including DNA and blood samples. This enables researchers to perform sophisticated analyses, Sieber said. The tissue is of very high quality, as brains are processed within two hours after death, she added. Related disorders include DLB, Parkinson’s disease with dementia, multiple system atrophy, and progressive supranuclear palsy. Banner recently joined the Parkinson’s Disease Biomarkers Program, a new portal that will enable researchers to submit requests for biomarker data and associated tissue requests to the Banner brain bank, Sieber said. Having brain tissue from multiple similar disorders helps researchers parse the potential contributions of unusual pathologies such as Marinesco bodies, inclusions that appear in the nucleus of dopaminergic neurons and multiply with age (see image below). The spots occur more often in neurons that contain Lewy bodies, and correlate with a drop in key dopaminergic enzymes, hinting that they may contribute to the dysfunction of these cells (see Beach et al., 2004).

Many other sites store Parkinson’s brains. The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study has more than 900 brains, many of them PD; they, too, have longitudinal data associated with them. Most of the 10 Morris K. Udall Centers of Excellence for Parkinson’s Disease Research supported by NINDS collect PD brains. Many of these are stored in large banks, such as the Brain Endowment Bank in Miami, that are accessible through the NeuroBioBank portal. Samples are of high quality, Sieber said.

Another Option: Prospective Tissue Collection

The non-profit National Disease Research Interchange offers customized collection of brain tissue. NDRI was founded in 1980 by Lee Ducat, whose son had diabetes, when she realized researchers were having a bear of a time obtaining pancreas samples for research. The organization is based in Philadelphia and receives funding from the NIH as well as charitable donations. NDRI does not bank tissues; rather, it procures them prospectively for specific research studies. To use the service, researchers fill out an online application. NDRI scientists peer-review each application, and if they consider the study relevant and feasible, they help the researcher procure donated tissue, said Thomas Bell, who directs scientific services at NDRI. NDRI even becomes a consulting research partner, helping researchers with all stages of a project, from writing grants to preparing papers. “It normally turns into a long-term relationship. We have had scientists with us for 30 years,” Bell said.

To find the tissues, NDRI turns to a network of partners from hospitals to transplant organizations. These sites recover the tissue and prepare it according to the researcher’s specifications. The service would be particularly valuable for neuroscience researchers who need tissues prepared according to unusual specifications, or who want to analyze matched tissues, for example eye and visual cortex from the same donor, Bell noted. NDRI can prepare whole brains, or only a portion, such as the hippocampus. The timeline to fill requests varies from weeks to months to a year, depending on the rarity of the tissue. For example, if an Alzheimer’s researcher had numerous specific requirements regarding age, clinical status, and genotype of donors, it could take NDRI several weeks to obtain each brain. For many researchers this timeline works well, as it may take that long to perform experiments on each sample, Bell said. The service would be unsuitable for researchers who wanted to analyze samples from dozens of brains at the same time.

NDRI accepts brain donations from individuals. All donations include demographic and clinical data provided by the hospital and next of kin, which are then de-identified. NDRI has international clients and participates in large, multi-year projects. As with brain banks, researchers pay tissue-recovery, processing, and shipping costs.

Many resources are ostensibly only a few clicks away. Alas, in practice, neuroscientists are still hampered by the limited numbers of some kinds of brain, particularly from minorities, controls, and people with rare diseases. These problems are unlikely to be solved without a funding commitment that would enable brain banks to expand and reach out to the public for more participation. “Brain banking is a very expensive undertaking, and it’s never been well-funded,” noted Deborah Mash, who runs the University of Miami Brain Endowment Bank.—Madolyn Bowman Rogers

References

News Citations

Paper Citations

- Vonsattel JP, Del Amaya MP, Keller CE. Twenty-first century brain banking. Processing brains for research: the Columbia University methods. Acta Neuropathol. 2008 May;115(5):509-32. PubMed.

- Beach TG, Sue LI, Walker DG, Roher AE, Lue L, Vedders L, Connor DJ, Sabbagh MN, Rogers J. The Sun Health Research Institute Brain Donation Program: description and experience, 1987-2007. Cell Tissue Bank. 2008 Sep;9(3):229-45. Epub 2008 Mar 18 PubMed.

- Beach TG, Adler CH, Sue LI, Serrano G, Shill HA, Walker DG, Lue L, Roher AE, Dugger BN, Maarouf C, Birdsill AC, Intorcia A, Saxon-Labelle M, Pullen J, Scroggins A, Filon J, Scott S, Hoffman B, Garcia A, Caviness JN, Hentz JG, Driver-Dunckley E, Jacobson SA, Davis KJ, Belden CM, Long KE, Malek-Ahmadi M, Powell JJ, Gale LD, Nicholson LR, Caselli RJ, Woodruff BK, Rapscak SZ, Ahern GL, Shi J, Burke AD, Reiman EM, Sabbagh MN. Arizona Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders and Brain and Body Donation Program. Neuropathology. 2015 Aug;35(4):354-89. Epub 2015 Jan 26 PubMed.

- Beach TG, Walker DG, Sue LI, Newell A, Adler CC, Joyce JN. Substantia nigra Marinesco bodies are associated with decreased striatal expression of dopaminergic markers. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004 Apr;63(4):329-37. PubMed.

Other Citations

External Citations

- National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center

- online query system

- BrainNetEurope

- NeuroBioBank

- best practice guidelines

- National Cell Repository for Alzheimer’s Disease

- online query

- Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program

- Parkinson’s Disease Biomarkers Program

- Honolulu-Asia Aging Study

- Morris K. Udall Centers of Excellence for Parkinson’s Disease Research

- Brain Endowment Bank in Miami

- National Disease Research Interchange

- online application

Further Reading

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.