Past Webinar

Betwixt and Intermixed—Dementia With Lewy Bodies

Quick Links

Introduction

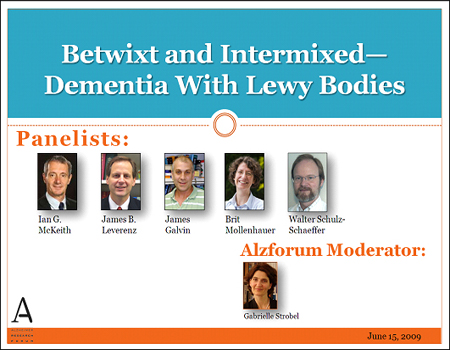

On 15 June 2009, we hosted a Webinar discussion with slide presentations by Ian McKeith at Newcastle University, UK, James Leverenz at University of Washington, Seattle, James Galvin, Washington University, St. Louis, Brit Mollenhauer of Paracelsus-Elena Klinik, Kassel Germany, and Walter Schulz-Schaeffer of the University of Goettingen and audio provided via a telephone line.

Editor’s note: Nearly 400 caregivers and scientists logged on for this 80-minute event. In addition, the Alzforum received more than 100 caregiver questions. This discussion aimed primarily at increasing awareness of DLB among scientists and physicians and therefore focused on scientific research, but clearly there is a great unmet need among patients and caregivers to have their questions addressed. The Alzforum editors have collected comments received in advance of the discussion and during the live hour into a caregiver comment page and are asking the panelists to respond to these questions. Please visit the Lewy Body Dementia Association website to view the first installment of answers to some of the most frequently asked caregiver questions.

- View/Listen to the Webinar

Click on this image to launch the recording.

Background

Background Text

By Gabrielle Strobel

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB)—a disorder at the interface of AD and PD—competes with vascular dementia for second spot (after AD itself) on the list of most common causes of dementia among the elderly. If you just said “Huh!” to yourself, you are not alone. Most people wouldn’t know how frequent DLB is, judging by the vastly smaller amount of attention it receives across the board, from neurologists, psychiatrists, scientists, and funders. But this may be changing. Twenty years after DLB came to be recognized as a clinical and pathological category in its own right, a growing number of researchers from both the dementia and the movement disorder fields believe that AD and PD—formerly viewed as separate domains—are connected across a spectrum, and that DLB links the two. Investigators who formerly focused on one of the two established diseases at either end of the spectrum are now developing an active interest in this mixed disease. In DLB, patients suffer from various combinations of Alzheimer and Parkinson signs, which are compounded by frustrating fluctuations in symptoms, visual hallucinations, visuospatial impairments, and, in many cases, rapid decline. “DLB may provide a link between AD and PD that will help us understand both disorders better,” said Ian McKeith of Newcastle University, UK.

Since 1995, a series of targeted workshops have focused on DLB, and on its neighbor on the PD end of the spectrum (Parkinson disease dementia, aka PDD). The workshops have sharpened the clinico-pathological picture of these diseases to crisper definitions that are applicable in the clinic. Clinicians know now that DLB and PDD patients respond especially favorably to cholinesterase inhibitors as was predicted from their postmortem neurochemical pathology. This past March, the latest in this series of small meetings, held in the German city of Kassel, broke new ground by proposing working groups that are charged with hammering out a collaborative research agenda for both biomarker development and presymptomatic diagnosis. Another priority the scientists set is molecular pathogenesis research that aims to unravel how the three main proteins known to underlie this disease spectrum—amyloid-β, tau, and α-synuclein—conspire in various ways to drive an individual person’s disease. What’s more, a new player on the DLB/PDD/PD end of the spectrum recently burst on the scene in the form of glucocerebrosidase, an enzyme of lipid metabolism whose gene appears to underlie a significant number of cases, and whose modus operandi in disease urgently needs to be figured out.

The Alzforum this past week began an ongoing series of daily stories that summarize recent advances on this topic. They form the background material for this Webinar discussion. So that you can come armed with questions about the latest and greatest, consider reading the introduction about spectrum neurodegeneration, tau in Parkinson’s, dementia with Lewy bodies, oligomers in DLB, AD, brain imaging markers, fluid α-synuclein markers, fluid progranulin markers, Parkinson’s gene reshuffling, and GBA as DLB and PD gene.

Buoyed by such and other advances, the DLB/PDD scientists hope to disabuse the field at large, as well as physicians who see these patients, of the entrenched but quite possibly outdated notion that DLB is rare (they say it’s not), vague (ditto), of indeterminate relationship to AD and PD (ditto), and complex (yes, but tractable). Join us for slide presentations and subsequent discussion. Send in your questions and comments before the live hour by typing into the comment box below. During the live event on 15 June, type into the GoTo Webinar comment field on your screen and the moderator will pose questions to the panel.

References

News Citations

- Spectrum of Neurodegeneration Comes to the Fore

- Et tu, Brute? Parkinson’s GWAS Fingers Tau Next to α-Synuclein

- Neither Fish Nor Fowl—Dementia With Lewy Bodies Often Missed

- Like DLB, Like AD—Do Oligomers Stir Up the Trouble?

- Ordnung, Please—Can Biomarkers Tame a Bewildering Overlap?

- Still Early Days for α-synuclein Fluid Marker

- Meet Progranulin, The Biomarker—A Simpler Story?

- Reshuffle Parkinson’s Genetics to Lay Out Its Pathways?

- More Than Gaucher’s—GBA Throws Its Weight Around Lewy Body Disease

Other Citations

External Citations

Further Reading

Papers

- Rocheville M, Lange DC, Kumar U, Patel SC, Patel RC, Patel YC. Receptors for dopamine and somatostatin: formation of hetero-oligomers with enhanced functional activity. Science. 2000 Apr 7;288(5463):154-7. PubMed.

- Milligan G. Neurobiology. Receptors as kissing cousins. Science. 2000 Apr 7;288(5463):65-7. PubMed.

Panelists

-

Ian McKeith, MD, FRSB, F Med Sci

Newcastle University,

Ian McKeith, MD, FRSB, F Med Sci

Newcastle University,

-

Brit Mollenhauer

Paracelsus-Elena-Klinik

Brit Mollenhauer

Paracelsus-Elena-Klinik

-

James Galvin, M.D., M.S. Washington University School of Medicine

-

James B. Leverenz, M.D.

Cleveland Clinic

James B. Leverenz, M.D.

Cleveland Clinic

-

Walter J. Schulz-Schaeffer, Leiter des Schwerpunktes Prion- und Demenzforschung

UNIVERSITÄTSMEDIZIN GÖTTINGEN GEORG-AUGUST-UNIVERSITÄT

Walter J. Schulz-Schaeffer, Leiter des Schwerpunktes Prion- und Demenzforschung

UNIVERSITÄTSMEDIZIN GÖTTINGEN GEORG-AUGUST-UNIVERSITÄT

Comments

�

Why do some people with LBD progress so rapidly and some progress so slowly, and why is it so difficult to diagnose?

�

I thank you all so very much for what

you are doing. We cannot cure this disease fast enough. Where are the clinical studies for this devastating disease?

�

Why is Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) so difficult to diagnose?

My husband declined mentally over a number of years. He was under the care of a neurologist, and a number of good doctors for other health problems. Each one agreed he had dementia but not until 8 month before my husband died was he diagnosed with DLB. I later found out he had all the symptoms. Why did it take so long?

Thank you in advance.

�

In 2004 at the age of 68, my father, who was always active, athletic, and highly intelligent, started hallucinating after having quadruple bypass surgery. He never fully recovered from the surgery, but continued having detailed hallucinations, was unable to dial a phone, use the dishwasher, etc. He was diagnosed with dementia and started on Exelon, Namenda and Seroquel. These medications helped tremendously. After researching, I was sure he had DLB. 18 months ago, I took him to UCLA and he was then officially diagnosed with DLB.

He is in a rapid decline now. He is bedridden, suffering from pressure sores, unable to communicate, doesn't open his eyes very often. He has lost a great amount of weight over the past 6 months, although he has a big appetite.

Is it normal for a person with DLB to continue to lose weight, even when there are eating? Also, do you recommend that a person continues on with the medications to the end?

Thank you for having this web forum.

�

My husband was a patient at Sun Health Research Institute in Sun City, Arizona. Charlie had a diagnosis of Lewy body dementia, but Dr. Marwan Sabbagh told us that the only way you know for sure is if an autopsy is done. We did that and found that my husband had not had LBD, after all. He had corticobasal dementia.

It was most helpful for our family to know what Charlie suffered with for three years. I wish more physicians would encourage patients to be tissue donors and give their families peace of mind when they know for sure what their loved one had.

�

My husband was diagnosed at the age of 52 with Alzheimer disease and three years later with DLB. It's been a tough six years. He does a lot of spitting and no one can figure out why. At times he can go for days without spitting and other times he will spit every few minutes. He is currently on robinal to help dry up the secretions. This has helped to reduce the amount of secretion but not the frequency. Has anyone else had this issue and, if so, is there any help with it or is this just what we have to live with? Thank you for any information.

�

My father had Alzheimer's and my mom had dementia with Lewy bodies. How concerned should I and my siblings be of ending up with either one?

�

I want to congratulate you for this excellent initiative.

My husband was diagnosed mid-2006, at the age of 67, with probable DLB, mainly because of his visual hallucination symptoms and attention deficit. Only over the course of the next year did mild Parkinson’s symptoms, such as body stiffness, appear. Today, about three years out, he has severe Parkinson’s symptoms, including stooped posture, "frozen behavior," severe equilibrium problems, uncoordinated walking (almost Creutzfeldt–Jakob-like), but no noticeable tremor.

I’d like to address this question primarily but not exclusively to Dr. Schulz-Schaeffer. Here is something that happens quite frequently: Although my husband has important cognitive loss and loss of speech, a sudden event, for example, loud shouting or a brisk movement, brings normal speech and attention momentarily back. It’s almost as if his brain got a boost by an electro-shock. My question: Is there any explanation, and how could this eventually be prolonged?

I recall a press release in April 2007 announcing that observations by your group offered a new understanding of the pathological processes behind neurodegenerative diseases such as DLB. Can your research explain my observation, and has it advanced since then? [Editor’s note: see Kramer and Schulz-Schaeffer et al., 2007.]

Here are questions mostly for Dr. Mollenhauer, who recently organized the Clinicopathological Conference on Dementia, held in Kassel last March:

References:

Kramer ML, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ. Presynaptic alpha-synuclein aggregates, not Lewy bodies, cause neurodegeneration in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurosci. 2007 Feb 7;27(6):1405-10. PubMed.

I found the Webinar to be very informative. I want to thank the Drs. for sharing their knowledge, and Gabrielle for asking important questions of the panel. One of the questions posed was should the ADNI Study include testing for α-synuclein protein to check for DLB.

I would like to propose that testing for α-synuclein should also be added as a protocol for the DIAN (Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network) Study since 90 percent of eFAD victims will also develop that pathology (see ARF related news story). There is so much information that researchers can learn from studying non-symptomatic members of families where there is 100 percent penetrance of AD if the mutant PS1, PS2, or APP gene is present. All the more reason that the DIAN Study is so important and should be carried on for numerous years after the initial six-year study is complete.

UNIVERSITÄTSMEDIZIN GÖTTINGEN GEORG-AUGUST-UNIVERSITÄT

Schulz-Schaeffer Reply to Vansteenkiste Comment

Indeed, our findings should be able to help explain the observations mentioned above. First of all, the observation that an particular ability that was believed to be lost reappears for a short period indicates that the cells responsible for the ability are still in place. Higher brain functions such as cognitive functions or speech require networks of nerve cells that communicate. In my opinion, the small aggregates do not immediately result in a loss of nerve cell communication; it is a progressively worsening process that results in loss of function when a critical threshold is reached. If the networks in principle still exist they may be stimulated to work for a short time. In the initial stages of the disease the partial loss of function may result in fluctuation of symptoms. In a more advanced stage short-time recurrence of function may occur.

The findings of my working group provide good evidence that training is the best way to prolong deterioration of brain functions. Electrophysiological experiments have shown that the use of synapses prevent the post-synapse from degeneration. In DLB, the problem seems to be the decrease of transmitter release from the pre-synapse, which leads to degeneration of the post-synapse. Training may be one way to slow down degeneration of the post-synapse.

Since our last publication we have been working on the link between the presynaptic protein aggregation with postsynaptic degeneration, aspects of the spread of the disease, and aspects of the selective neuronal vulnerability.

�

I understand from the comments of Prof. Schulz-Schaeffer that as long as the networks exist, they may be stimulated to work for a short time, suggesting that training is the best way to prolong brain functions.

But in an advanced stage of the disease, such training isn't possible anymore, although short-time recurrence of function may occur. How could such recurrence then possibly be induced ?

�

Thank you for making this available to the researcher and caregiver communities -- the Alzforum is a tremendous resource for us all. Three years ago I lost my father to Parkinson's with dementia after many years of watching him and my mother (his primary caregiver) struggle with this disease. As a physicist working on developing PET instrumentation with potential application for differential diagnosis and earlier diagnosis, I am doubly interested in this live discussion.

There were a number of presentations bearing on these subjects at the Society of Nuclear Medicine meeting that just concluded, and which coincided with the live discussion. A number of people attending that conference I'm sure would have added to your live attendance, and I'll thank you on their and my behalf for making the discussion available for us now that we've returned to our work. Dr. Chet Mathis received the Lassen prize from the Society of Nuclear Medicine at this year's meeting for his work creating the Pittsburgh Compound B PET amyloid imaging radiotracer. While, as has been noted here on the Alzforum, there is as yet no radiotracer on the horizon for alpha synuclein, there were presentations on a number of dopaminergic tracers both for PET and SPECT. In the talks and in the aisles, there was discussion of possible potential for future combinations of these methods in contributing information for diagnosis of mixed dementia.

I and others are hopeful of being able to contribute to this, in concert with other biomarker methods and working with those who are developing the treatments which we all look forward to with such hope.

�

Found the Webinar very interesting. We have a dual Parkinson's/AD diagnosis. I strongly suspect Lewy body disease. The decline over spring has been so rapid we are struggling and a little overwhelmed at times.

�

I would like to know how many younger people live with DLB. My husband was only 42 when his symptoms started. I always hear of elderly, not much about younger patients. Thank you for this discussion. No matter what the age, it is an awful disease for all of us.

Newcastle University,

Reply to Chirco Laurie

There isn't any systematic information about age of onset of DLB, but the situation is probably similar to Alzheimer disease, i.e., that young onset does occur although is relatively uncommon. The sparse literature suggests that very early onset Lewy body disease (a few cases begin as early as the twenties) is usually a combination of quite severe parkinsonism plus dementia; at older ages the clinical picture is much more variable. ApoE status or other genetic determinants may play a part in age of onset even in cases which have no obvious familial pattern.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.