A Tribute to Robert Katzman

Quick Links

Robert Katzman was a pioneer in bringing the multidimensional problem of Alzheimer disease out of obscurity and into the forefront of medical, scientific, and social agenda of this country. As a physician-scientist, teacher-scientist, and activist-advocate, he cast a giant shadow. He was among the first to redefine Alzheimer disease as a major public health problem. Katzman's 1976 landmark editorial "The Prevalence and Malignancy of Alzheimer's Disease," published in the Archives of Neurology, and the 1977 Conference on Alzheimer's Disease (sponsored by NINCDS, NIA, and NIMH at the National Institutes of Health), which he organized along with his lifelong collaborator Robert Terry, and Katherine Bick, were important in attracting the attention of the medical-scientific communities.

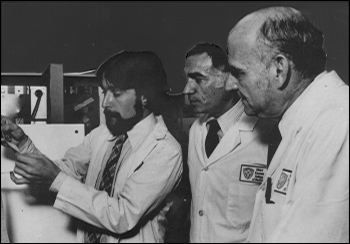

Peter Davies, Robert D. Terry, and Robert Katzman.

Image credit: Peter Davies

Robert Katzman was born 29 November 1925, in Denver. He completed his undergraduate studies at the University of Chicago and graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1953. He did his internship at Boston City Hospital and his residency in neurology at the Neurological Institute at Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital. He was chairman of neurology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, in the Bronx, from 1964 until his move to the University of California, San Diego, in 1984. There he served as chairman of the department of neurosciences and the director of the Alzheimer's Disease Research Center, which was one of the first of five such centers to receive major support from the National Institute on Aging (NIA). He retired in 1995 as a professor emeritus of neurosciences.

His research interests were eclectic, covering a broad range of topics from neurochemistry to neuroepidemiology. His scientific career began at Harvard and at Einstein College of Medicine when he studied the movement of potassium ions and amino acids across the blood-brain barrier. He gradually moved toward an interest in the edema that occurs in response to toxins and tumors, and in the composition of cerebral spinal fluid. In the early 1970s, his research at Einstein began to focus on Alzheimer's and Aging (Bronx Aging Study). In collaboration with Robert Terry, an Einstein neuropathologist who had studied Alzheimer's since 1960, Katzman began systematic studies of clinical-pathological features of the disease. At Einstein, the Katzman-Terry team began to recruit, train, mentor, and collaborate with talented new investigators, both basic scientists and clinicians. Thus, Katzman and Terry became the major progenitors of the new wave of investigators that eventually became leaders in the field.

In the mid-1970s Katzman played a key role as an advisor in my efforts to develop the brain aging and Alzheimer's research programs at the National Institutes of Health. He was one of the handful of people who helped launch the Alzheimer's Association; he served as the first Chair of the Medical and Scientific Advisory Board and helped to start the Association's research support program. In subsequent years he served on numerous committees and Boards in an effort to promote the cause of Alzheimer's.

Robert Katzman's impact on the field cannot be overstated. Without his relentless effort to advance the research, either directly by his own work or through his students and collaborators, the field of Alzheimer's would still be obscure. The community mourns the loss of a giant leader.—Zaven Khachaturian.

References

No Available References

Further Reading

No Available Further Reading

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

Deceased

I was lucky enough to work with the two giants of the Alzheimer disease field in the early days (1977-1982), Robert Katzman and Robert D. Terry. What an environment that was for a young scientist! Between them, Bob and Bob knew everything there was to know about Alzheimer disease and the other common dementias. Neither was shy about expressing their opinion of new work in the field, especially mine. I learned so much from the time we spent together, and I owe a great debt to these two wonderful mentors.

Boston University School of Medicine

The picture posted above is basically how I remember things. I started in Peter's laboratory in the Department of Pathology at Einstein in 1984. At that time, from the student's perspective, there was a trio of heroes—Peter Davies, Robert Terry, and Robert Katzman. In addition, there were also other young members who, though not quite as famous, filled out the group. These other members included Leon Thal (the charismatic young neurologist with his ever-present huge mustache), Dennis Dickson (the young fellow, riding his bike to work), David Armstrong (cholinergic anatomy), Sue Yen (tau, microtubules, and protein aggregation), and Howard Crystal. However, Peter and the Bobs are grouped together in my mind, with Bob Katzman and Bob Terry being the two senior members who really organized Alzheimer's research at Einstein. In my mind, Bob Katzman and Bob Terry had almost defined the field of Alzheimer disease, creating the transition from having physicians consider it a secondary diagnosis synonymous with aging, to a diagnosis of a real disease that could be treated. I didn't see Bob Katzman as much, because his venue was more in neurochemistry and clinical neurology, but I did see Bob Terry a lot. Being present with Bob Terry at a brain cutting was always something done with immense trepidation because Bob would quiz me about numerous details related to neuroanatomy and the neuropathology of Alzheimer disease. Wrong answers were chastised in his classic paternal tone, which I can still hear!! Meanwhile, the group as a whole (led by Bob Katzman) was at the forefront of defining Alzheimer disease in those early days, and it was a very, very exciting experience.

Time moved forward, Drs. Katzman, Terry, and Thal left for UCSD, Drs. Dickson and Yen went to Mayo, Dr. Davies stayed put, but also directs the Alzheimer's program at North Shore Hospital, numerous graduate students have left Peter's laboratory and become stellar investigators in their own right (for example, Bob Bowser and Inez Vincent), and the field of Alzheimer's/neurodegeneration research has exploded. Dr. Thal became a star in his own right, establishing the premier clinical organization for clinical trials in Alzheimer disease at UCSD; we all miss him dearly. Dr. Dickson has become another star, and is one of the world’s premier neuropathologists. The growth of the field of Alzheimer's research is largely attributable to the efforts that Robert Katzman and Robert Terry made early on to identify Alzheimer disease as a major health problem for the elderly and a field worth pursuing in its own right. This is a tremendous legacy left by Dr. Katzman, and one for which we can all be thankful.

Washington University School of Medicine

When I entered the Alzheimer's research field in 1984, Robert Katzman already was legendary. Early on he foresaw, perhaps as no one else did, the coming epidemic of Alzheimer's, labeling it as a "major killer" in his 1976 landmark editorial in the Archives of Neurology, "The Prevalence and Malignancy of Alzheimer's Disease." He attracted an extraordinary group of colleagues, including co-"Giants in the Field" Robert Terry and Leon Thal, to study the illness when he was at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and then convinced them to move with him in 1984 to the University of California, San Diego, instantly establishing that institution as a world leader in Alzheimer’s research. He was very proud to be a founder of the national Alzheimer's Association, an organization to which he was deeply committed. Robert Katzman was the overwhelming choice to be the inaugural recipient in 1988 of the Potamkin Prize for Research in Pick's, Alzheimer's, and Related Diseases from the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), the most prestigious award in Alzheimer's disease. In collaboration with the Alzheimer's Association, the AAN recently established the Robert Katzman, M.D., Fund to provide a clinical research fellowship for a junior neurologist interested in Alzheimer’s research. This is a most appropriate legacy, as he was a highly effective and dedicated mentor for many neurologists who continue to revere him.

The original 10 Alzheimer's Disease Research Centers (ADRCs) were established by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) in 1984 and 1985, and the directors of each ADRC began meeting together twice yearly with NIA staff to discuss common problems and issues. The potential for dissension and acrimony was great, as each director was certain that the clinical and scientific initiatives at his ADRC were "best" and deserved the most attention (and funding) from NIA. Gentle but firm guidance from highly respected and sage directors, including Bob Katzman, Tuck Finch, Bill Markesbery, and Leonard Berg, prevented this potential from being realized. Indeed, with the leadership of these individuals, the ADRC program developed into one of common purpose and remarkable fellowship that persists to this day. The camaraderie established by Bob Katzman and the other early pioneers of organized Alzheimer's research was genuine and lasting. When Leonard Berg died in January 2007, Bob was one of the individuals I telephoned personally to convey the news. Regrettably, that was the last time I spoke with Robert Katzman, a true "giant" of Alzheimer's disease research.

University of Washington

I have served on advisory panels and site visit teams since the work now being carried out by the NIA was part of the mission of the Adult Aging Branch of the NICHD. I am most proud of the small role I played in supporting the pioneering work of Bob Katzman and his closest colleague, Bob Terry, while they were establishing their famous research program at Albert Einstein in the 1970s. Bob and his colleagues gave us a 10-year head start in terms of the science they did and their roles in creating a public awareness of its importance. The passing of Robert Katzman to me is symbolic of a "passing of the torch" to the remarkably large and dedicated cohort of "second-generation" AD investigators.

I will also remember Bob Katzman for special things he did for friends and colleagues. An example that comes to mind occurred during a visit to San Diego soon after he and Bob Terry moved to UCSD. I told him that my kids were keen on seeing the desert country. The next morning he delivered his Grand Cherokee Jeep for our use, together with a set of helpful instructions on where to go and what to see! My late wife Julie was enormously impressed.

Methodist Neurological Institute

When I went on the site this morning I was actually quite saddened to

learn that Bob Katzman had died. I knew and respected him for his

compassion and leadership in scientific discoveries and bringing Alzheimer

disease front and center as a major public health problem. Non-medical

people usually become aware of illness when a famous person goes public

or when it hits one's family. Bob Katzman was a medical "giant" who left

a great legacy by bringing AD to the attention of the medical

community and providing seminal insights into the pathogenesis of disease

through his own scientific efforts and those of his collaborators and

followers. He'll be missed.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.